Master Sgt. Orlando Reyes was taken aback when he was ridiculed on social media for not having a Combat Action Ribbon after being named the 2014 Military Times' Marine of the Year.

While Reyes, a logistician, had three deployments to Iraq under his belt, his duties had never put him in a position to participate in a combat engagement.

"I didn't expect it to go so far," Reyes said of the criticism he experienced. "In today's era of social media and anonymity of computer posts, people are going to say what they want and there's no repercussions. They think, because of the rack of someone's chest, they have insight into that individual."

The growing discord surrounding Combat Action Ribbons — the award issued by the sea services for active participation in ground or surface combat — is troubling some leaders.

The online criticism illustrates an increasingly vocal perspective among Marines, especially those in the ground combat community. This perspective holds that a Marines' worth and authenticity is closely connected to combat experience, and that those who lack this experience are less deserving of respect.

In some ways, this viewpoint is a natural outgrowth of 14 years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. But Commandant Gen. Joseph Dunford is making it clear that he has no patience for it.

"The coin of the realm is the eagle, globe and anchor," Dunford told Marine Corps Times in a February interview. "It doesn't matter what [military occupational specialty] you have, it doesn't matter what deployments you've been on, it doesn't matter what ribbons are on your chest — it's about being a Marine. So that will be my message to Marines."

'Stacking each other up'

When Dunford named Sgt. Maj. Ronald Green as his senior enlisted adviser in January, most Marines expressed interest in his background and the reputation he'd built as a thoughtful and involved leader. But a loud minority couldn't get past the stack of ribbons on his chest.

Green, a career artilleryman, did not have a Combat Action Ribbon, the award issued by the sea services for active participation in ground or surface combat.

"No CAR ... not the right guy for the job," one reader groused on e commenter on the Marine Corps Times' Facebook page following at the news of Green's selection. Others complained that the newly chosen sergeant major of the Marine Corps didn't measure up to other senior leaders Marines who had earned combat valor awards.

Green took the comments in stride.

"We don't go around counting one another's ribbons, and, you know, kind of stacking each other up," he told Marine Corps Times. "We're actually too busy to do that."

When a Marine is tested in combat, Dunford said, how he or she performs is important. But, he added, the same can be said for every task and field to which Marines are assigned.

"Most Marines don't pick their MOS [military occupational specialty]," he said. "Most of us do things that the Marine Corps tells us to do. And it really is about the quality of your performance in the task that you've been assigned that's most important, once you wear the eagle, globe and anchor. And that's how I'm going to approach this issue."

These comments from Dunford, a decorated infantry officer, represents a rebuke to the grunt-centric culture that glorifies combat experience above all else. What remains to be seen, though, is whether the commandant's message is enough to change the culture — or if only time can do that.

Green isn't the only Marine leader to face criticism for lack of a Combat Action Ribbon. Though criticism at Green's selection was the most recent high-profile incident in which criticism for lack of a Combat Action Ribbon came to light, other Marine leaders have also taken heat for their ribbon stacks. Now-retired Gen. James Amos, the 35th commandant and the first from the aviation community, received so much heat online for his lack of a CAR that an aide once jumped into the fray to defend him.

"[Amos] has been in many a fight ... probably killed more enemy with his F-18 than any single company of grunts," the staffer wrote in a Facebook posting before thinking better of it and deleting the comment.

The division is a relatively new challenge for the Corps.

The Combat Action Ribbon did not even exist until February 1969, when the Navy and Marine Corps adopted it in the midst of the Vietnam War. It was retroactively applied to combat engagements stretching back to 1961, and later extended to cover combat dating from the December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack that marked the U.S. entrance into World War II. The Coast Guard would adopt the Combat Action Ribbon much later, in 2008.

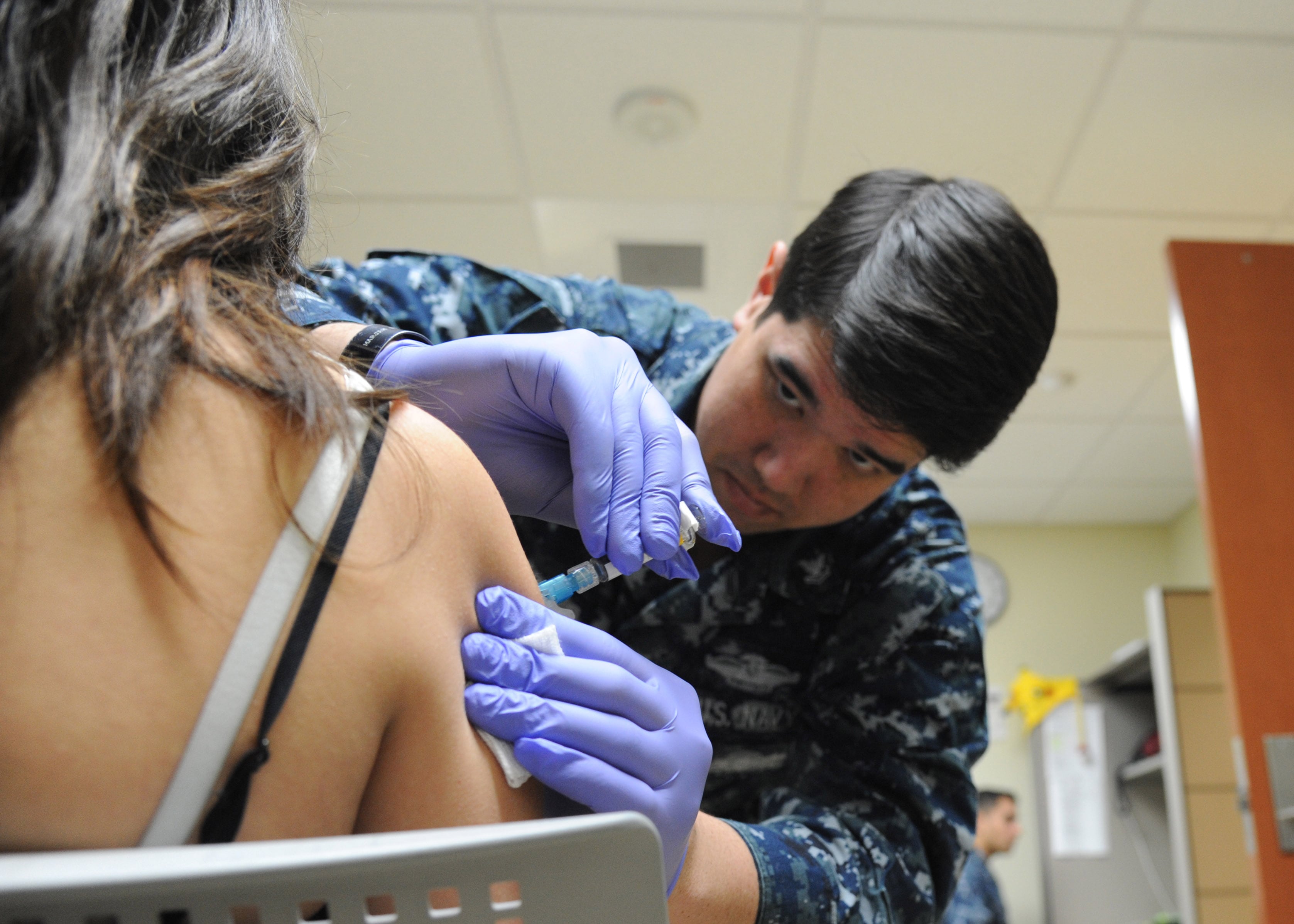

Marines evacuate the area as an MV-22B Osprey lands in Thailand during during Exercise Cobra Gold 2014. There is a divide between some Marines who believe combat experience trumps all, and those who feel it should be respected, not revered.

Photo Credit: Cpl. Zachary Scanlon/Marine Corps

And prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Combat Action Ribbons were a rare sight rather than an expected one.

Andrew Northam, a Marine infantry veteran who served from 1990 to 1994, recalled the reverence that surrounded the CAR during that largely peacetime period.

"[CAR recipients] were more revered when I was in," Northam said. "A guy had three Combat Action Ribbons in my unit and he was like a god to us."

Because there were so few opportunities to earn a CAR, he said, they weren't treated like a badge of authenticity. And combat experience wasn't seen as a rite of passage among Marines, as it sometimes is today.

Northam, who deployed to Somalia in late 1993 to support Operation Support Hope, earned a Combat Action Ribbon there, but did not receive it until years later when it was retroactively authorized after he had left the service.

Receiving the award, even late, made Northam realize its a significance as a recognition of what he experienced.

"When we looked back on our experience in Somalia, we always thought we should have gotten it; we felt a little robbed by that," he said. "We were taking mortar fire, in an offensive posture. It was a little bit of vindication having that."

Still, Northam believes the hype surrounding the ribbon has gone too far. When news of Green's selection as the Corps' top enlisted leader SMMC broke, Northam fired back at Green's critics on the blog USMCLife, calling the belief that senior leaders needed to sport a CAR "fanatical."

"Marines do not get to choose their duty stations; you go where you are assigned," Northam wrote. "As we wind down our nation's longest period at war, the Corps is facing many challenges; two of the biggest are dealing with the overall military drawdown and more importantly, dealing with returning vets and [post-traumatic stress]PTSD. Can [Green] conceivably do this without that precious ribbon? I believe so."

An imperfect award

Even today, following a decade and a half of war in two theaters, Combat Action Ribbons are less common than some perceive them to be. According to Marine Corps Manpower and Reserve Affairs, only 20,855 of the 184,567 Marines currently on active duty boast at least one CARcombat action ribbon.

With combat arms fields — including infantry, artillery and mechanized units — making up roughly 22 percent of the active-duty force, that means less than half of active Marines in combat arms rate the award. That figure is likely to keep dwindling as wartime deployments are replaced with training, humanitarian and crisis response missions.

Logan Stark's Marine Corps experience was in many ways different from Northam's. He enlisted in 2007, as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were in full swing.

An infantry assaultman, Stark was surrounded by Marines who had already deployed and earned their Combat Action Ribbon. There was definite pressure, he said, to join their ranks.

"When I was a boot, there was the whole concept of, 'you aint sh-- until you got your Combat Action Ribbon," Stark said. "When you're coming up in the fleet, especially the time that I was in, you felt like that was a requirement of being an infantryman in the Marine Corps. It became something that you strived for, that you needed to be that complete Marine."

But there was a dark side to the CAR obsession, Stark soon realized. While deployed to Afghanistan's Sangin valley in 2010 and 2011, Stark said he encountered Marines who would insert themselves into patrols they didn't belong on, just so they could earn their Combat Action Ribbon. The experience left a bad taste in his mouth and altered the way he viewed the award.

"Is it a badge of honor and do I wear it with pride? Yes," said Stark, now a filmmaker and writer for the website Funker350. "But it only holds so much weight. I don't think we should judge people based on whether or not they have it. For some reason, we want to use these really easily identified symbols ... When did we get away from getting to know a person and getting to know their background before judging them?"

Stark said he hopes the Marine Corps will find a balance in which combat experience is honored, but viewed with perspective.

"I want to hear about a person's experiences; I want to learn from their combat," he said. "It shouldn't be a pedestal thing; it should be a way to learn from each other."

Reyes, the master sergeant, said he also observed Marines going out of their way to get a CAR during his deployments to Iraq. The trend wasn't limited to junior Marines, he said; he saw troops that were senior to him finagle their way onto convoys and other missions outside the wire to earn the coveted award. When they did so, Reyes said it wasn't only just unnecessary, but it was also dangerous.

Now assigned to School of Infantry-East out of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Reyes said he encourages junior Marines to value their comrades' other Marines' character and leadership qualities more than their ribbon stacks.

"We get so bent out of shape with these ribbons and awards that we sacrifice the most important thing to us as Marines: our integrity," he said.