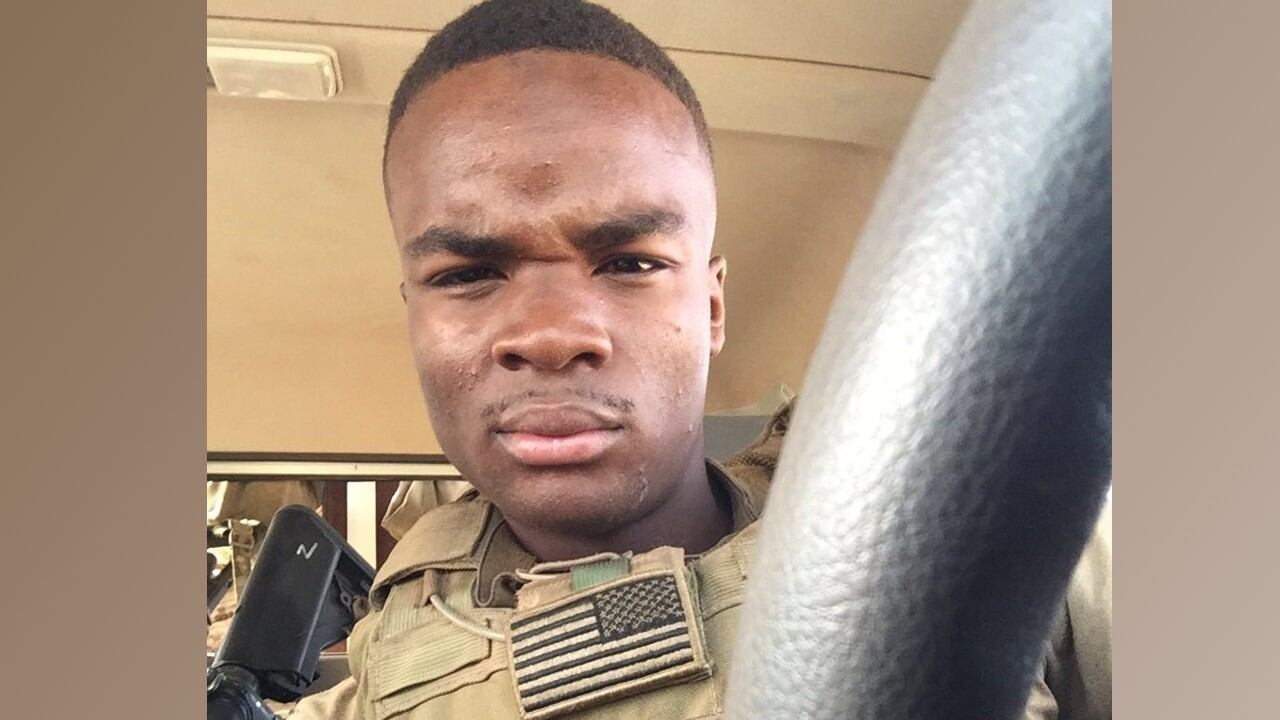

Early in the four-year investigation I led with my ABC News colleagues, which unfolds in the new feature documentary “3212 UN-REDACTED” about the 2017 ISIS ambush of a Green Beret team in Tongo Tongo, Niger, the family of fallen Sgt. LaDavid T. Johnson recounted a startling phone call.

LaDavid’s widow Myeshia Johnson and his mother Cowanda Johnson said that the day after LaDavid was reported missing in action in the Oct. 4, 2017, gunfight, they received a phone call from an Army officer informing them that the young mechanic had been captured by the enemy. Three of his 10 teammates had lost their lives in an attack by more than 100 jihadist fighters that stunned the public, the U.S. military, Congress and the Trump White House.

“I get a call saying that they have an American soldier, and they are willing to do a trade,” Myeshia Johnson told us in an interview for the documentary.

Myeshia, who at the time was 25 and pregnant with the couple’s third child, said the caller told her the information had come from a villager in a remote part of northwest Niger, who claimed that militants were holding LaDavid captive and wanted to swap him for an unnamed ISIS commander’s “brother” who was being held in prison.

“They just said they’re willing to do a trade,” Myeshia recalled as she sat across from me wearing one of LaDavid’s camouflage Army jackets. “In my mind, they still didn’t find my husband. I don’t know what’s going on. So any little thing that somebody tells me, I’m thinking, could this be my husband?”

The next day, however, brought no new news of a prisoner swap ― just a knock on the door from a U.S casualty assistance officer that dashed those hopes.

“He told me, ‘As of Oct. 6, Sgt. Johnson went from missing in action to KIA,’” Myeshia remembered. “Everybody went bananas. I was screaming and crying, and my mother-in-law was throwing glasses and screaming and crying. She’d fallen on the floor. She was throwing things.”

“Oct. 6, 2017 was a day I think I went insane,” Cowanda told us.

Had Sgt. LaDavid Johnson truly been captured after the Oct. 4 ambush? The military would later say that he had not. But that hardly satisfied a family left reeling by grief, doubt and a string of inconsistent information from the Army.

The mystery of that Army phone call stating that LaDavid Johnson had been captured by ISIS — which our investigation ultimately determined was based on an uncorroborated intelligence report quickly knocked down at the time by military intelligence officers in Niger — is one of the earliest examples of conflicting and false statements by U.S. military leaders given to the families of the four fallen soldiers of Operational Detachment-Alpha 3212, which are scrutinized in the ABC documentary streaming on Hulu beginning Nov. 11.

Despite a public pledge in late 2017 by then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford to “go to every last length to provide the families with accurate information,” the Johnsons told us they felt the exact opposite happened.

In fact, so did the families of the other three other fallen soldiers: Staff Sgt. Dustin Wright, Sgt. 1st Class Jeremiah Johnson and Staff Sgt. Bryan Black.

They have spent four years fighting back against the core claims made by U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM): that their loved ones were part of a small Special Forces team that went on a rogue mission unapproved by senior commanders to kill an ISIS commander, and that they were inadequately trained, incompetent compared to other special operations teams, and unprepared to face the enemy, as former top commander Marine Gen. Thomas Waldhauser claimed publicly in 2018.

But for LaDavid Johnson’s family, the lingering doubt over whether the young man — known in his Miami neighborhood as the “Wheelie King” for his legendary ability to ride his bike for miles on a single wheel — was captured and had his wrists bound behind his back and possibly tortured before he was executed, as news reports claimed at the time, is almost unbearable.

No one from the military ever explained to them who called or why they were told that LaDavid had become an ISIS prisoner, family members said. It was just one of the many pieces of confusing information given to the families that we dug into for the film.

“If I could go back and figure out who gave them that first report I’d f***ing choke the s*** out of them. I mean, it’s just, it’s egregious that somebody would share that unconfirmed report with them and unconscionable that the family would be given conflicting statements,” Mark Mitchell, the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Acting) overseeing U.S. special operations at the time, says pointedly in the film.

The family says they believed for a long time that LaDavid had, in fact, been captured, bound and executed by ISIS, despite denials by military officials.

“I believed that. I felt that my husband was captured,” Myeshia told us. Over time, she has come to believe it less and less as more information from our three-year investigation came to light.

As alleged in the ABC/Hulu documentary I co-produced with director Brian Epstein and editor Andrew Fredericks, this was merely the first of numerous private and public misstatements and missteps made by the U.S. military regarding the Tongo Tongo gunfight — and LaDavid Johnson’s death, in particular.

RELATED

The cloud of doubt would spread over the families of the other soldiers. Our investigation found that they, too, had encountered officials who engaged in questionable behavior, presented false allegations, buried material facts, failed to explain peculiarities, and misled them in order to protect senior leaders, according to other top commanders and officials we interviewed on camera and off.

Mitchell, himself a highly-decorated Green Beret colonel, strongly criticized the official investigation of the attack, making him the highest-ranking whistleblower to come forward. The investigation was led by the AFRICOM commander Gen. Waldhauser’s own chief of staff, in what Mitchell and many others say was a clear conflict of interest.

ABC’s investigation since 2017 found no support for Waldhauser’s core claims about the team’s “true task and purpose,” including what he stated about the team’s supposed effort to find intelligence on the whereabouts of Jeffery Woodke, an aid worker kidnapped in 2016 who remains in captivity.

The actions of the chain of command and AFRICOM devolved even further following the Oct. 5, 2017 call informing LaDavid’s loved ones that he’d been a prisoner of ISIS, known for beheading hostages.

Army officers arrived at the home of LaDavid’s parents Richard and Cowanda Johnson in a working-class neighborhood of Opa-Locka, Florida, and undertook questionable actions, the family alleges.

Then-3rd Special Forces Group commander Col. Bradley Moses — the only person in the chain of command who never received any sort of reprimand, despite overseeing the ill-fated missions of ODA 3212 — told them that LaDavid had been missing in action for 48 hours because he was thrown from his Toyota Hilux during the first hour of the firefight, the family said.

“Col. Moses told me that LaDavid was in the back of the truck. The truck hit the tree,” Cowanda says in the film. “He said that LaDavid flew 900 meters and wound up in the bushes. Yes.”

Col. Moses, in a call to me last year denied that he ever told the family that LaDavid was thrown from his truck.

But the now-retired commander for Northwest Africa special operations did admit to doing something else the Johnsons found fishy, which was asking for the last text messages LaDavid sent during the mission to his family. “As a commander I thought, maybe this is something that could help put a puzzle piece in place to have a broader understanding of what happened,” Moses explained to me.

The family refused to show Moses the texts because the request seemed suspicious to them, since he was not part of AFRICOM’s investigation into the incident. Family members, however, provided the messages to me.

LaDavid texted his young wife Myeshia about a baby stroller she wanted to purchase, not about details of the mission.

It was, as the mission plan had called for, a reconnaissance mission where they would attempt to lock onto a cell phone signal associated with an ISIS commander named Doundoun Cheffou, which had been detected by a U.S. drone. The idea was track but not kill Cheffou, more than a dozen sources inside the military and intelligence community told me.

LaDavid texted Myeshia from his base at Oulluam, Niger, at 5:52 a.m. on Oct. 3, minutes before the team rolled outside the wire. “Going on mission bae,” he wrote.

Later during the mission, Myeshia sent LaDavid a selfie to show him how her pregnant belly was growing. Hours passed without a response, so she sent another note through WhatsApp. “Bae,” she tapped into her phone. LaDavid never saw the photo or her affectionate text. By then he was dead.

Sgt. LaDavid Johnson’s body was recovered by another team, ODA 3216, after village children found him on Oct. 6 amid five spent 5.56 mm shell casings from his M4 carbine and brass from enemy AK-47s.

Officials failed to explain LaDavid’s horrific wounds, the details of which his family poured over in the autopsy report, in photos and in other official documents. They also failed to explain why, evident among the 50 autopsy photos reviewed by ABC News, his remains arrived home with two pairs of pants and a French-made jacket in the body bag, which didn’t belong to him. One of the Green Berets who recovered his remains told me that villagers had picked up discarded military clothing in the desert and placed it with LaDavid, whose head they covered with a white scarf.

The family’s confusion and questions didn’t end there.

Moses and 2nd Battalion commander Lt. Col. David Painter largely remained out of sight for four years during the ensuing multiple investigations of the incident in Niger, avoiding the families and the press while family members say some Pentagon officials slow-rolled the release of information, refusing to turn over AFRICOM’s redacted 268-page report to the families until June 2019 — 20 months after the attack — at a meeting at Fort Bragg, N.C., where Myeshia and Cowanda Johnson walked out in frustration.

The information the Johnson family had shared with us about the phone call informing them of LaDavid’s supposed capture was partially laid out deep inside that report’s redacted pages, which stated that the Nigerien Army had received “an unverified report” from a villager “that a hostage had been taken to a village near the Mali border.” The U.S. military believed the report pertained to LaDavid but soon “the unverified report proved false,” AFRICOM stated.

“It didn’t shake out because it was completely false,” one Special Forces operator with the 3rd Special Forces Group, who was part of the recovery effort in Niger, told me. Special operators prepared to raid a village but an officer said he simply dialed up a source they had in the village.

“We said, ‘Hey, is ISIS there?’ The answer was no,” the operator told me. “They went down that rabbit hole along with whoever called LaDavid’s family. They were planning an operation based on it before anybody bothered to ask, ‘What was the source of the report?’”

In another macabre twist, Maj. Alan Van Saun told me that when he accompanied AFRICOM investigators to Tongo Tongo a few weeks after the gunfight, they dug several of LaDavid’s teeth out of the sand under the thorny tree where the AFRICOM report said he made his last stand. His parents still hold onto them and it gave them another reason to fear he was executed.

Was the official military autopsy conclusive in knocking down any claims he had been captured, bound and executed?

I asked a former top medical examiner and retired Navy captain who worked at Dover and also led worldwide POW-MIA recovery efforts for the military, Dr. Edward Reedy, to examine the written autopsy report and 50 photos.

“I see no evidence of binding, torture or restraint,” Reedy told me this year, agreeing with the official findings. “He has a tremendous number of gunshot wounds.” But none were point-blank execution style wounds.

The veteran medical examiner said he was saddened but hardly surprised by the poor communication with the Johnson family.

“I can really relate to this family’s anguish. I’ve been involved in a number of these cases where communication between leadership and the family has not been clear. It has caused no end of problems,” Dr. Reedy said.

RELATED

Related: Survivors and fallen soldiers of Niger ambush awarded valor medals, but questions linger

Eventually, the fallen soldiers of ODA 3212 were honored with valor awards, although some were downgraded by commanders. LaDavid Johnson received the Silver Star for his actions, which included suppressing enemy fire with an M240 machine gun and sniper rifle that Staff Sgt. Bryan Black had taught him to use. One teammate said LaDavid, the team mechanic, fought “just like a Green Beret.”

But Myeshia let her feelings be known at the 2019 valor award ceremony, at one point turning away from Army officers in tears. “I was angry. angry,” she says in the film. “I wanted my husband to be here with me. No award, medal, anything could bring him back. I’m angry, and I’m still angry to this day.”

LaDavid decided on the Niger trip that he wanted to go to Special Forces Selection and become a Green Beret, his comrades and widow told me. His comrades had deployed with him to Niger previously and asked for him to join them on the 2017 trip.

The autopsy photos show that inside one of the body bags shrouding his remains, which were stripped of everything except his bloodied t-shirt and pants and his bullet-pierced helmet, was a small cloth patch adorned with three skulls on a shield, emblazoned, “ODA 3212,” and neatly placed on his chest by a comrade for the journey home to Miami.

Last July at Fort Bragg, Lt. Gen. Francis Beaudette presented LaDavid Johnson and Jeremiah Johnson with honorary Green Berets, an unprecedented honor given to support soldiers.

James Gordon Meek is an award-winning national security investigative reporter for ABC News. He has covered the rise of Al Qaeda since 1998, from the Millennium Plot to reporting from the ground outside the Pentagon after a hijacked plane hit it on Sept. 11, 2001, and on combat patrols with Special Operators and U.S. infantrymen in Afghanistan.

Editor’s note: This is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.