Bonfires lit the beaches of Aola Bay on Guadalcanal’s northeast shore as two companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion splashed ashore before dawn on November 4, 1942.

The Raiders — led by Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson — were joining U.S. Army and Marine Corps ground forces under the command of Marine Major General Alexander Vandegrift in the battle for the largest of the Solomon Islands — then raging for nearly three months. American units controlled a knobby headland at Lunga Point, where they seized a Japanese airstrip, christening it Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine flier killed at Midway. Now Vandegrift wanted to expand the Americans’ toehold on Guadalcanal with a second airstrip east of Aola Bay.

Carlson’s 2nd Raiders were to secure the beachhead for the arrival of naval construction workers and army garrison troops, then leave aboard supply and transport ships. But as the battalion was setting foot on the island, Japanese destroyers landed 1,500 reinforcements halfway between Lunga Point and Aola, and the 2nd Raiders’ mission took a sharp turn. Vandegrift deployed Marine and army units to ambush the new Japanese arrivals, and ordered Carlson’s Raiders to mop up enemy soldiers who managed to escape the trap. Then the Raiders were to clear areas of enemy activity west of the Henderson Field perimeter. It was a straight-line distance of just over 18 miles, but the men would not be traveling in a straight line over open terrain. Instead, they would be forced to hack their way through dense, unforgiving jungle foliage in extreme heat.

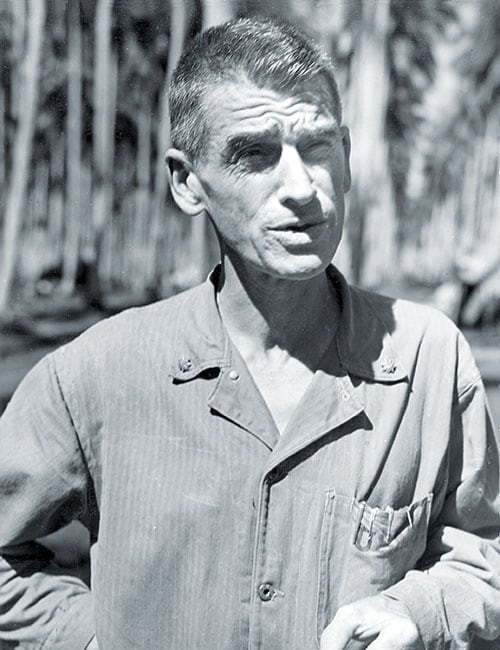

On November 6, the Raiders, accompanied by 150 native scouts and porters, set out for the Bokokimbo River in a snaking, mile-long line. Rolling coastal hills and plains gave way to condensed, dark green jungle interspersed with sunbaked clearings. Beyond the jungle loomed a jagged blue-green spine of volcanic peaks, some towering nearly 8,000 feet. The Bokokimbo was 10 miles away, but the men’s heavy packs and the thick “wait-a-minute vines,” razor-sharp kunai grass, swollen creeks, and muddy swamps slowed their progress. The Raiders covered only five miles that day, prompting their lean, hawk-faced commander to take the lead and accelerate the pace. Evans Carlson was an impatient man and he had much to prove — for himself and for his Marine Raiders.

IN THE TRADITION-BOUND Marine Corps, Carlson was an iconoclast and an anomaly, a tactical theorist with a literary and philosophical bent, and possessed an unusual circle of acquaintances. During a military tour as an American language and intelligence officer in China in the late 1930s, Carlson was an observer with Mao Zedong’s Eighth Route Army as they outfoxed the Japanese. He was intrigued by their emphasis on small unit tactics and flexible, guerrilla-style raids. He admired how the Communists stripped away most of the distinctions between officers and enlisted men and, after battles, did not mistreat their prisoners. From his experience, Carlson adapted an ethos he called “Gung Ho” — an Anglicization of Chinese for “work” and “together.”

When the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, created the Marine Raiders in February 1942, he tapped Carlson to command 2nd Battalion. Carlson incorporated Gung Ho into their regimen and adopted a Spartan lifestyle for his Raiders. He instructed his men not only how to fight, but to understand why they fought. He also emphasized a Darwinian approach to leadership — any officer who failed to meet Carlson’s standards would be swiftly relieved of command.

Carlson put the 2nd Raiders to the test at Makin Atoll in August 1942, but the unit had underperformed and the mission had come close to failure. Intended as a swift guerrilla-style strike to divert the Japanese from the American invasion at Guadalcanal, the action instead devolved into a conventional firefight, with Carlson reacting to the enemy rather than seizing the initiative. The Raiders made repeated attempts to evacuate the island amidst chaos, with waves swamping many of their rubber landing craft, stripping them of weapons, supplies, and even clothes. In those uneasy hours, an exhausted Carlson overestimated the enemy presence. He dispatched terms of surrender to the Japanese commander, but the messenger was killed before delivering the note. And when the Raiders finally made it off the atoll, during the pandemonium of their escape they unintentionally left behind nine men, whom the Japanese captured and later beheaded. “The way it ended up,” recalled B Company Private Ben Carson, “It was damn near ‘every man for himself.’”

Desperate for heroes and good news, the American public celebrated the Makin Raid as a victory and greeted the exhausted Raiders as conquering heroes. But Admiral Chester W. Nimitz later criticized Carlson, especially for entertaining the notion of surrender. And Carlson himself was all too aware that the reality of the Makin Raid was far from what the public envisioned.

Now, three months later, with Vandegrift’s open-ended orders to find, pursue, and destroy Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, Carlson saw an opportunity for redemption — a chance to validate his unorthodox, idiosyncratic Gung Ho doctrine, get 2nd Raiders back on track, and maneuver on his terms to find and destroy the enemy.

ON NOVEMBER 7, the Raiders’ long column reached a deserted riverside village littered with empty Japanese ration boxes and cigarette packs. Carlson halted, posted sentries, and permitted his men to bathe. That afternoon, they heard rifle fire echo across the Bokokimbo River. The Raiders grabbed their weapons and waded across the neck-deep water. There, they surprised Japanese foragers. Three or four fled, but the Marines killed two. “They’d killed a hog for dinner,” remembered C Company Raider Darrell Loveland. “Of course we left them in the jungle and roasted the hog.”

Starting the next day, the Raider column bent northwest to Binu, the westernmost of the villages still occupied by locals. Carlson established base camp there to await the remainder of his battalion — the B, D, and F Companies, who hiked overnight through torrential rain to link up with Carlson’s command group on November 10. The Raider force, now totaling about 600 men in five companies, was just three miles east of where 1,000 Japanese were reported to be retreating south along the Metapona River.

On the dawn of November 11, Carlson assigned four patrols to scour the Metapona from Asamana, a village northward to the coast. The patrols would fan out ahead of his command group, arrayed laterally south to north. He believed the formation would give him maximum flexibility to meet threats as they arose.

Soon after 10 a.m., the southernmost patrol, Captain Harold Throneson’s C Company, stumbled into a wooded enemy bivouac, killing about two dozen Japanese. However the enemy recovered quickly, pinning down the Marines with rifle, machine gun, and mortar fire. Recalled C Company’s Loveland: “They had us in a hurting position.”

Throneson radioed his situation to Binu base camp, and Carlson sniffed an opportunity: with the Japanese force engaged with C Company, he could swing one of his other companies around the distracted enemy forces. He ordered Captain Charles McAuliffe’s D Company to move toward Throneson’s men while Captain Richard Washburn’s E Company maneuvered south and hit the Japanese from the rear.

One of Washburn’s platoon commanders in E Company was Carlson’s son — 1st Lieutenant Evans C. Carlson, who had tried four times to transfer into 2nd Raiders. His father, reluctant to appear to play favorites, had denied each request. When the lieutenant put in his fifth request, however, the battalion’s officers helped persuade their commander to allow his son into the unit.

With young Carlson in the lead, Washburn’s men reached Asamana, where they killed a handful of Japanese fording the Metapona. Washburn suspected that Throneson and his force had run afoul of a rear guard positioned to protect the main enemy force crossing the Metapona, and aligned his platoons in an ambush anchored by light machine guns. The gambit felled many more Japanese mid-stream — but the enemy rallied. Washburn’s men withdrew into the jungle, regrouped, and mounted an audacious counterattack. At noon, as two of his platoons charged straight at the enemy, a third got behind the Japanese and hit them with deadly crossfire from the east.

A standoff of charge and countercharge lasted into the afternoon with the two sides closed to within 30 paces of each other. By mid-afternoon, Washburn’s Marines, exhausted and parched, were running low on ammunition and water. When a sudden enemy mortar barrage signaled a renewed attack, Washburn withdrew his company north through a gully. Two of his men had been killed and another mortally wounded, but E Company had killed some 130 Japanese.

Not all the Raiders performed as well. While leading D Company southward, McAuliffe and his nine-man squad came under heavy fire that separated them from the rest of the company and blocked their efforts to rejoin them. McAuliffe finally extracted his squad and returned to Binu, reporting that the rest of D Company had been wiped out. Carlson was furious — and doubly so when D Company’s gunnery sergeant arrived a few minutes later with the remainder of the Marines, very much alive.

As the day wore on, Throneson called in mortar fire on the Japanese as most of C Company’s pinned-down squads scrambled to reach the relative safety of the tree line. Throneson himself, however, stayed put. Carlson arrived with elements from two companies, whose advances revealed that the main Japanese force was pulling out. He radioed for aircraft to bomb and strafe the retreating Japanese for the remainder of the day and, after dark, returned to Binu.

True to his strict, unforgiving approach to leadership, Carlson swiftly relieved Captains McAuliffe and Throneson of command. He tacitly acknowledged their valor, but could not ignore that under duress Throneson had failed to take the offensive, while McAuliffe had gotten separated from his command. Still, 2nd Raiders had earned a decisive and indisputable victory, eliminating around 160 enemy soldiers at a cost of 10 killed and 13 wounded. Carlson soon reprised his improvisational ways — instead of exposing his main body to possible ambush, he would now set traps with smaller patrols, then flank and envelop the Japanese in force.

He also discarded his benevolent, Mao-style stance on POWs. The day after the Asamana battle, while scouring the C Company battlefield, Raiders found the body of Private Owen Barber—staked to the ground, mutilated, and castrated. “If you take a prisoner,” Carlson told the Marines. “He’s gotta eat your food, he’s gotta drink your water, and you gotta worry about having your throat cut.” Henceforth, the Raiders took no prisoners.

BEGINNING NOVEMBER 12, Carlson’s men aggressively cleared the area south of Binu and west to Henderson Field. Carlson realized the enemy used Asamana as a rendezvous point, and constructed a hunter’s blind. During the first 18 hours, Marines bushwhacked 25 enemy stragglers — most of them messengers unaware the Marines had overrun the position. He allowed larger groups of foliage-cloaked enemy troops into mortar range and hit them, too. After two days and two nights, another 116 Japanese lay dead with no Raider casualties.

As Carlson was clearing and advancing across Guadalcanal, his company commanders, too, were coming into their own. “We were running into small groups of Japanese who’d become separated,” said B Company’s Ben Carson. “We were wiping them out with flanking operations all the time.”

On November 14, Captain William Schwerin was leading an F Company patrol south of Binu when they happened onto a small Japanese position on the west bank of the Balesuna River. Schwerin scouted the area and noticed a lone sentry guarding a narrow entrance. When other Japanese soldiers called the guard for chow, Schwerin led his men in threes through the entrance and into position for an attack. “When you hear my shotgun,” Schwerin whispered, “give ’em hell!” He edged closer to the defile where the enemy soldiers were eating. He fired; the Marines killed 15 Japanese.

On November 17, Carlson reached the Henderson Field perimeter and conferred with Vandegrift, who then ordered the 2nd Raiders to swing south to pursue Japanese remnants, silence their artillery, and disrupt their supply lines.

Doing so, however, meant battling Guadalcanal itself: smothering foliage, wearisome heat and humidity, vermin, and especially disease: malaria, jaundice, dysentery, and “jungle rot,” as Marines called ringworm. “All of us had sores on our legs. We were wading streams and rivers all the time,” Ben Carson said. “Our corpsmen were running out of medication.” A bottle of Merthiolate that Carson had brought from Hawaii was quickly emptied.

Ultimately, the environment claimed more Raiders than the enemy did. Dysentery plagued many men; some cut out the seats of their dungarees and let nature take its course. C and E companies, in the jungle the longest, saw their ranks shrink 80 percent. In their month-long odyssey, 225 Raiders got sick — six-and-a-half times the unit’s battle losses.

Moving southwest, the Raiders encountered steep coral ridges and denser jungle. By November 29, they came to a narrow spine separating the Tenaru River from the Lunga River. Roping up, then down the cliffs, they spotted two empty encampments: one with a 75mm mountain gun and another with a 37mm anti-tank gun. After destroying the Japanese weapons, the Raider squads diverged to scout two rain-soaked trails near the Lunga. Along one trail, F Company’s Corporal John Yancey stumbled across an enemy bivouac — 100 Japanese soldiers, their weapons stacked. Yancey and his six men instinctively started shooting, which disrupted the surprised enemy enough for the Marines to rush to better firing positions.

“What up?” William Schwerin asked over the din.

“I’ve flushed a covey,” Yancey shouted. “Send up a squad!”

In 30 minutes of lethal precision, with Americans shouting “Hi, Raider!” to identify themselves and avoid crossfire, Yancey’s fire teams killed 75 enemy soldiers, earning Yancey a Navy Cross.

Finally, Carlson was able to report no major Japanese movement to the east. Vandegrift ordered 2nd Raiders back to Henderson Field. Carlson’s men were now a few miles to the southwest; between them and the Marine perimeter loomed Mount Austen, a 1,500-foot peak. The Japanese held the summit. Carlson told Washburn to shepherd the three most exhausted companies — C, D, and E — around the mountain and back to Henderson Field. He would lead the A, B, and F Companies up the mountain.

On December 3, in steady rain, Carlson led the three companies in scaling Mount Austen’s south face. “It was arduous,” recalled Gene Hasenberg, who gutted out the six-hour ascent on an ankle painfully throbbing from a boil he had just lanced. Marines seized the crest, from which a series of ridges radiated. An encounter with a Japanese patrol soon exploded into a two-hour battle, with each side desperately trying to envelop the other through dense vegetation. “We had them outnumbered and we had so much automatic firepower,” Ben Carson said. “I figured the BAR I carried saved my life on Mount Austen.” When the shooting was over, 25 Japanese lay dead. Four Raiders were wounded, with one — A Company’s 1st Lieutenant Jack Miller — seriously hurt. The next day, while descending hastily to get Miller to the Marine perimeter for surgery, Carlson’s lead elements strode into a Japanese ambush. During the two hours needed to rout the enemy, Miller died — a mournful prelude to the Raiders’ arrival to Henderson Field that afternoon.

Despite the toll that death and illness took on 2nd Raider Battalion, their long patrol was a tactical success. For Carlson, the battalion’s actions helped validate not only their fighting prowess, but also the new, unorthodox doctrine he had worked so hard to instill in them.

A Marine colonel, greeting the column of ragged, skinny men treading into the safety of 1st Marine Division lines — many of them bearded after a month without razors —offered to drive them to Henderson Field. Carlson thanked the colonel but declined his offer. After having survived a month in the Guadalcanal wilds, accomplishing the objectives his way, and accounting for 500 Japanese dead with only 16 Americans killed and 18 wounded, the leader of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion had one more thing to prove.

“The Raiders walked in,” Carlson said. “The Raiders will walk out.”

This story was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of World War II magazine, a sister publication of Military Times. Read more from World War II magazine and other HistoryNet publications at historynet.com.

The Cactus Air Force fought at Guadalcanal

Arsenal: The first stealth aircraft