One Navy Reserve chief said he is skipping the vaccine for now because of how fast it was created. “That’s not a risk I’m willing to take,” he said.

A young Army captain said he fails to see the point in getting the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines because he already had COVID-19 and wants to see his parents get vaccinated first.

“The Army is all about managing risk,” the junior officer said. “The risk to reward doesn’t make sense to me yet.”

An Air Force Technical Sergeant doesn’t like to put anything foreign into his body and will decline the vaccine as long as it’s voluntary. He plans to “detox” the vaccine out of him when the military makes the immunization mandatory, despite the fact that there exists no scientific basis for purging a vaccine from one’s body.

“I know my immune system is strong enough to prevent me from getting it,” he told Military Times.

These are the ranks of the vaccine hesitant in the U.S. military, men and women who for one reason or another are declining to get the for-now voluntary COVID vaccines, even as the brass pushes the fact that such vaccines are safe, effective and help protect everyone.

Getting the force vaccinated is a readiness issue for military leaders. For the past year, COVID outbreaks have hobbled the ability of units to carry out their mission, most prominently aboard the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt last spring, when the virus forced an emergency port call to Guam and roughly a quarter of the 5,000 sailors onboard tested positive.

Health officials outside the military are stressing the importance of getting as many jabs into as many arms as possible, to dampen the impact of future surges or more virulent strains of the virus.

Dozens of servicemembers from across the branches reached out to Military Times in recent weeks to share their thoughts on the vaccines. Many of them requested anonymity to speak candidly about their views,

Many troops support the vaccine efforts and say they wanted the shots as soon as possible to protect themselves and others while returning to a pre-pandemic normalcy.

But others expressed skepticism with the vaccines, pointing to the speed in which they were developed, the temporary “emergency” authorization by the federal government and even the fact that higher-ups are pressuring them to get the shot.

Military leaders have acknowledged in recent weeks that roughly a third of servicemembers have declined the vaccines when it was offered.

For those who have confidence in the science behind the vaccines and their overall safety, the distrust comrades feel about this scientific counter-punch to a historic pandemic — and the misinformation fueling some of that skepticism — can be frustrating.

For one Navy petty officer 1st class, getting the vaccine was a no-brainer. The petty officer said she thinks the Trump administration’s mixed messaging and falsehoods about the virus’ deadliness and the efficacy of wearing a mask has spilled over into vaccine skepticism.

“People still refuse to accept that COVID is deadly, let alone be willing to get vaccinated for it,” she said.

“I just want to get back to normal and getting vaccinated is the only way to get there,” she told Military Times.

RELATED

“There’s so much misinformation on social media and the internet, it’s incredibly frustrating,” she added. “By volunteering, I hope to prove it all wrong.”

The E-6 said she works as a recruiter and regularly interacts with the public, increasing her risk of catching the highly contagious coronavirus.

“I feel very passionate about the vaccine because I grew up in a home full of asthmatics and I worry about my family every day,” she said. “I know what it’s like to see someone struggling to breathe.”

She also got the shot to set a good example for her coworkers, but when her office was offered the vaccine, she said she was the only one who took it.

One Air Force tech sergeant told Military Times that just three airmen in his 50-member unit have opted to get the vaccine.

The NCO counts himself among those who will forego it. He said he is wary in part because of the military’s past experimentation on servicemembers, such as the Edgewood/Aberdeen experiments, where the military tested dangerous chemical warfare agents, protective clothing and pharmaceuticals on troops from 1955 to 1975.

A malaria drug once widely used by the military was later designated a drug of last resort in 2013 due to side effects that mimic post-traumatic stress.

“My other coworkers do not want to be guinea pigs, just like many soldiers and civilians…throughout history were subjects to government testing,” the Air Force NCO said.

The NCO said that, because he has been around people who have tested positive for COVID, he does not believe the virus poses a threat to him. “If I have to take the vaccine, I will go on a hardcore detox to get it out of my system ASAP, just like I do with any other vaccination,” he said.

There exists no scientific evidence that someone can “detox” a vaccination out of their body, according to Matthew Nathan, a retired Navy vice admiral and former surgeon general for the sea service.

“If one could flush the vaccine, then in theory one could flush the virus out if they knew they had just encountered it by being in close proximity to someone who had it,” Nathan told Military Times. “That is not possible either.”

But such false claims speak to the misinformation or disinformation that servicemembers and other Americans face as the vaccines’ availability become more widespread.

The science-less claim that residual vaccines can be flushed from someone’s system had been a point of advocacy for years among the so-called “anti-vax” crowd, Nathan said, an idea built on the fact that older vaccines sometimes contained aluminium and mercury compounds in very low doses that acted as preservatives.

“Even in that case, there has not been a scientific basis of harm, though there is still much emotion about it,” he said.

The politicization of the pandemic, and the variety of specious information circulating online, can make it hard for the average servicemember to parse science-based truth from baseless fiction, allowing things like vaccine denialism to flourish, Nathan said.

“This goes to a deeply rooted problem in this country,” he said. “Vaccines are just one symptom of it. People are subscribing to conspiracy theories about all kinds of things.”

Nathan encouraged servicemembers to read up on the vaccines and noted that large-scale testing of the vaccines would have exposed any major health risks.

People are more likely to have a health problem stemming from the virus itself rather than a problem related to the vaccine, he said, adding that while young people have not seen as many severe cases as older people, the disease can still strike in ways no one fully understands yet.

And while the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are new, the modified RNA technology at the heart of the shots is not new and has been in development for years, Nathan said.

“Based on the initial science and based on the depth of mRNA studies that have gone on years before, there’s nothing to indicate this is going to create long-term effects,” he said.

While the services are largely powerless to stop an E-7 from spreading vaccine misinformation to his or her younger charges, Nathan said the branches should plaster photos everywhere showing other enlisted leaders getting the shots in order to counter misinformed opinions.

“For every master chief that’s suspicious of the vaccine, you’ve got to find 10 others that get it and put their picture and video of them getting it everywhere,” he said. “If I’ve got 10 others saying, ‘young man, young lady, follow me,’ that can be powerful.”

Nathan added that he thinks take rates will increase as more people get the shots.

“You’ll see a lot more people watch their shipmates and their friends and neighbors get the vaccine and not blink an eye,” he said. “They’ll have more confidence in it.”

The pandemic will not stand by so skeptics can see how people do five to 10 years after their vaccine shots, he said.

“We know what’s going to happen if we don’t get vaccinated,” Nathan said. “We know the number of people that are going to die.”

Nathan urged younger uniformed vaccine skeptics to consider the fact that their vaccination helps slow the virus from spreading to other, more vulnerable people, because it has one less person to spread through.

“Do your part to give this virus no place to live,” he said.

Nathan recalled a conversation recently with a concerned mother whose teen daughter has lung problems and was about to get the vaccine.

The mother said she was nervous about her daughter getting the shot.

“I said, to the best of my knowledge no one has succumbed or died from the vaccine…yet 4,000 a day are dying of COVID,” he recalled. “She said, that’s good enough for me. Her child got the vaccine and did fine.”

Some hesitancy toward the vaccines may have to do with the fact that they aren’t given to cure a current condition.

“People have a different mindset” when given a drug to prevent illness rather than cure a current malady, he said.

But Nathan noted that, in addition to the large-scale trials the vaccines underwent, COVID cases in nursing homes are dropping as residents and staff were among the first to receive the jabs in December.

“The vaccines are doing what they’re supposed to do,” Nathan said. “We’re seeing it’s safe and effective and it’s doing its job.”

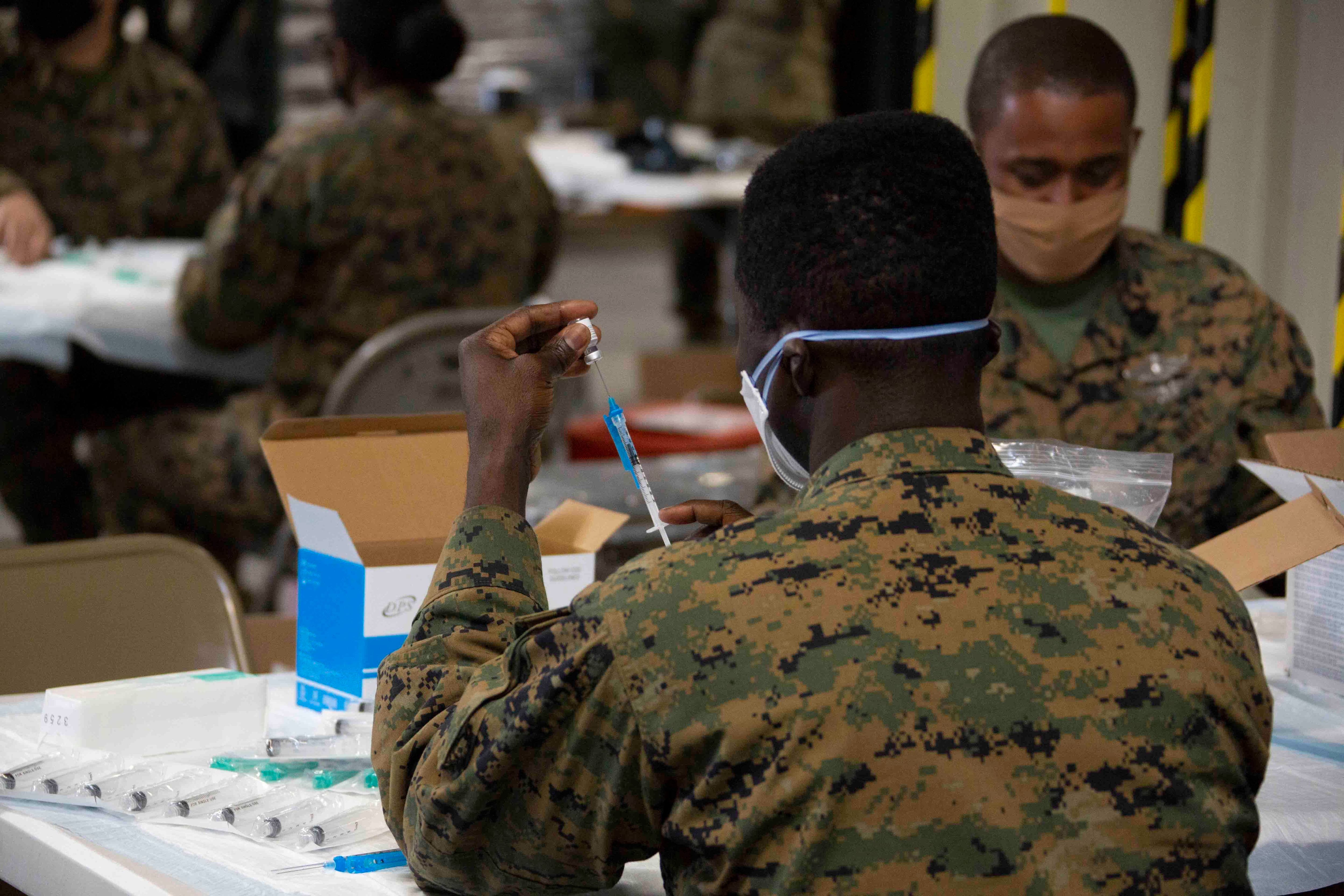

Some sectors of the military are trying to fight the bad gouge making its way through the ranks regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccines.

At Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Marine Corps officials are directly fighting online misinformation and disinformation, according to a March 1 Carolina Public Press report.

“It is a challenge to combat misinformation that Marines are seeing on social media,” Lt. Col. Thomas Turner, who leads active-duty vaccination planning at the Marine base, told the news outlet. “But that is one of our principal lines of effort here. We have to inoculate the force from the virus, and we have to inoculate the force for vaccine misinformation.”

“It happened so quick”

Public health officials stress that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were developed quickly, but are tested, safe and effective.

Some of the reasons the vaccines came out so fast is because the mRNA technology at the heart of the vaccines has been in development for years and was ready to fire up when the pandemic struck, according to a fact sheet from Johns Hopkins University, a leader in science and medical research.

China also shared genetic information early about the novel coronavirus, which gave vaccine developers an early start on finding the vaccine.

While some testing process stages were conducted simultaneously to gather data as quickly as possible, no steps were skipped in the process, according to Johns Hopkins.

Still, several troops told Military Times that this speed makes them wary, as does the fact that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the vaccines under emergency-use authorization.

“My hesitancy is that it happened so quick,” said a Naval Reserve chief who is a healthcare provider in his civilian job and does not plan to get the vaccine at this time.

The chief said he is by no means an anti-vaxxer, and that his hesitancy stems from these vaccines alone. “As science evolves, as research evolves, my opinion can change, but it might take decades before I can say this is safe,” he said.

And while adverse effects of the vaccine have been statistically minimal, the chief still worries.

“I’m not necessarily comfortable with taking that risk, even if it’s not statistically significant,” he added.

Others wonder why they should get the shots when they’re young, healthy and will still have to live within the military’s at-times onerous COVID restrictions.

RELATED

“If we get the full vaccine, we are still required to ROM/quarantine and we are still required to wear masks,” a Navy petty officer said. “If we still have to follow the same frag orders, then might as well wait until it is mandatory.”

Navy officials have released guidance in recent weeks that will offer less restrictions to units with a high vaccine take rate and could result in less-stringent ROM requirements for vaccinated sailors.

The 30-year-old sailor said she doesn’t judge other servicemembers regarding whether or not they get the shot.

“For those who want to get it, I support them, but I also support the people who don’t want it,” she said. “Everyone has their own opinion on COVID and the vaccine.”

Another Navy petty officer in the medical field said he trusts the science but feels like the “undue command influence” of the brass pushing him to get the jab fosters distrust.

The petty officer said he “felt pressured” to get the vaccine by leadership at his local branch health clinic and resents the implication that refusing the vaccine harms combat readiness.

“I understand the importance of wearing a mask, practicing responsible social distancing and I believe in the safety of the vaccine,” he said. “My concern lies with military leadership not understanding that the distrust of the vaccine comes mostly from the push for vaccination, and not a mistrust of the efficacy and safety of vaccines approved under (emergency use authorization).”

A lieutenant colonel in the New York Air National Guard said he jumped at the chance to get the vaccine.

Other than a sore arm, the officer said his main feeling was “a sense of relief.”

“It’s one of the first major steps towards getting back to normal,” he said. “That should be everybody’s goal, with the military leading the way.”

Those holdouts who still refuse the shot frustrate him, he said.

One fellow guard member has been on active duty for nearly a year, at the frontlines of the COVID response, and is still declining the jab, the officer said. “Every time I see this person, I want to slap them upside the head,” the officer said.

An Army medic and sergeant 1st class said the Army should be making a stronger pitch for the vaccine. He said he was disheartened that less than a third of his 1,000-member unit has opted to take the vaccine so far.

He pointed to past examples of when the Army has mounted aggressive and effective education efforts.

“When given the choice for opting into the new retirement plan, units were given ample time and resources to educate their Soldiers about the benefits and drawbacks,” he said. “I have not seen any products besides a handful of posters that were put up in our own aid stations.”

While some soldiers are simply “denialists who have made up their mind” regarding the shots, the E-7 said he thinks that “a larger population is either indifferent or unexposed to the facts, and who might opt in if they just learn more.”

His command hasn’t screened to better understand vaccine hesitancy, but the medic suspects a lot of it is “due to political hogwash not based in fact.”

“I am incredibly frustrated by my comrades’ ill-informed beliefs about the vaccines and lack of enthusiasm to return things to normal,” he said. “Despite the largest studies in modern vaccine history being conducted in record time, they still distrust it and would rather risk the severe health complications from the disease itself.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.