WHITEFISH, Mont. — Carlin Houston, a 23-year-old paratrooper with the U.S. Army’s 501st Airborne Infantry Regiment, traversed the slopes of Big Mountain with relative ease, looking every bit the part of a seasoned snowboarder — Flylow jacket, baggy Goretex pants, mirrored goggles — despite having never set foot on snow.

Born and raised in Texas and following in the footsteps of the three generations of Houston men before him, the young servicemember enlisted in the military shortly after graduating from high school. He’s dutifully served his country ever since, having twice deployed overseas, including last summer when he assisted with the large-scale evacuations and airlifts at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, a military operation that captivated the world as U.S. forces ended their presence in the two-decade conflict.

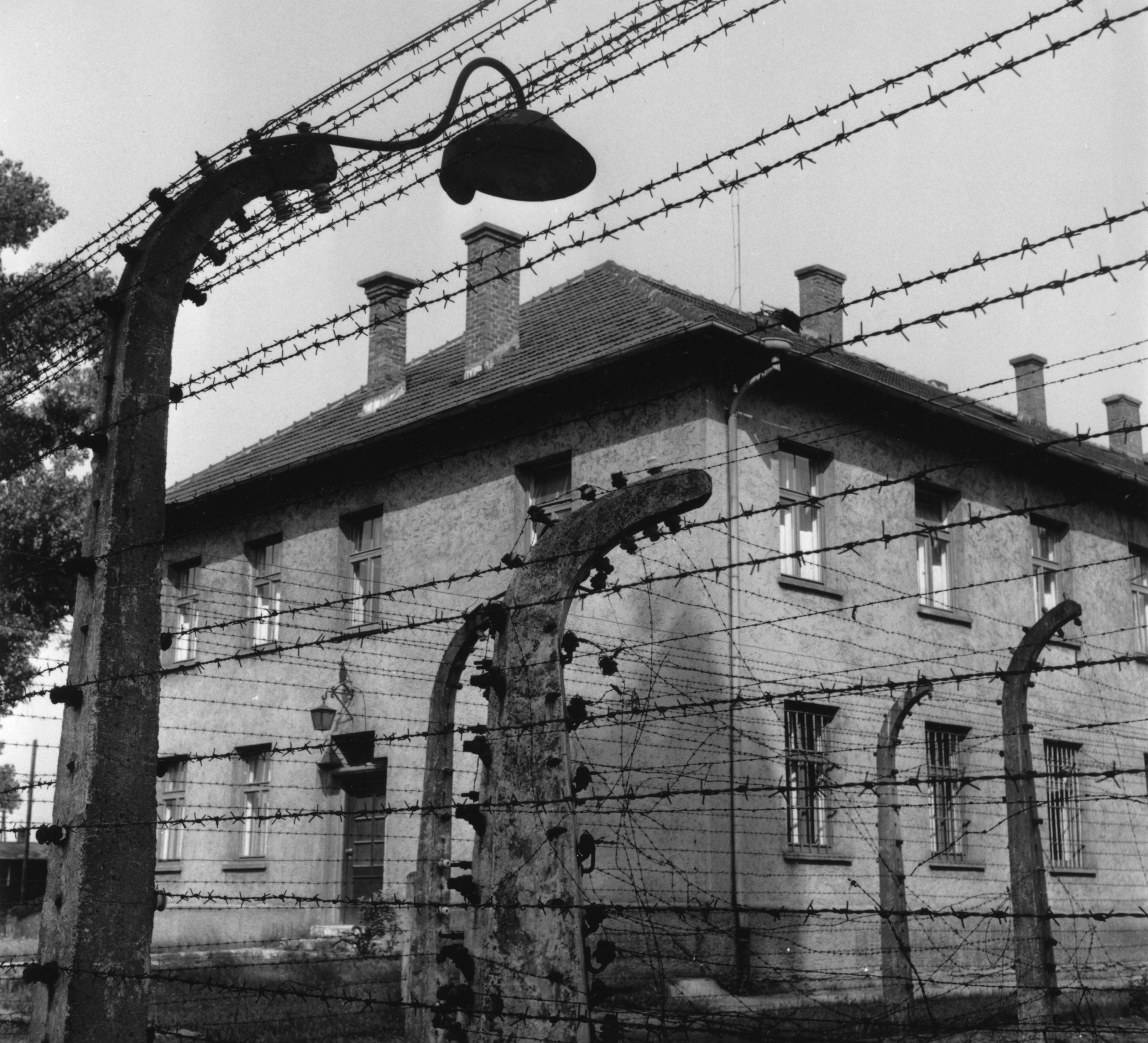

It was a bittersweet experience, Houston said, imparting a mix of emotions that ranged from pride and a sense of accomplishment to guilt and a sense of futility, particularly after suicide bombers detonated explosives near the airport gate, killing 13 U.S. service members while serving up a painful reminder of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks that were the war’s catalyst.

RELATED

“After 20 years we were the Battalion to end the War in Afghanistan, which is something I am proud of. I’m super grateful to have had that opportunity,” Houston said, explaining that, were it not for a last-minute mix-up in communication, he would have been much closer to the site where the bombs detonated, helping screen refugees at the airport gate. “We were supposed to be there, on that detail, and that weighs pretty heavily on me. It’s the survivor’s guilt, you know?”

Given the extent of his military service since entering adulthood, a period he’s primarily spent training at the base in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Houston hasn’t been able to carve out much time for R&R or personal reflection, much less find an opportunity to learn to snowboard.

Until now.

“My whole life I’ve wondered what it would be like to experience snow, and as it turns out I love it,” Houston said on a recent powder day at Whitefish Mountain Resort, savoring a piping-hot basket of fish and chips at Ed and Mully’s, a mainstay bar and eatery at the ski area on Big Mountain. “I’ve been overseas twice but I still see this as an opportunity to expand my horizons and figure out what life might look like outside of the military. I want to figure out what’s next for me.”

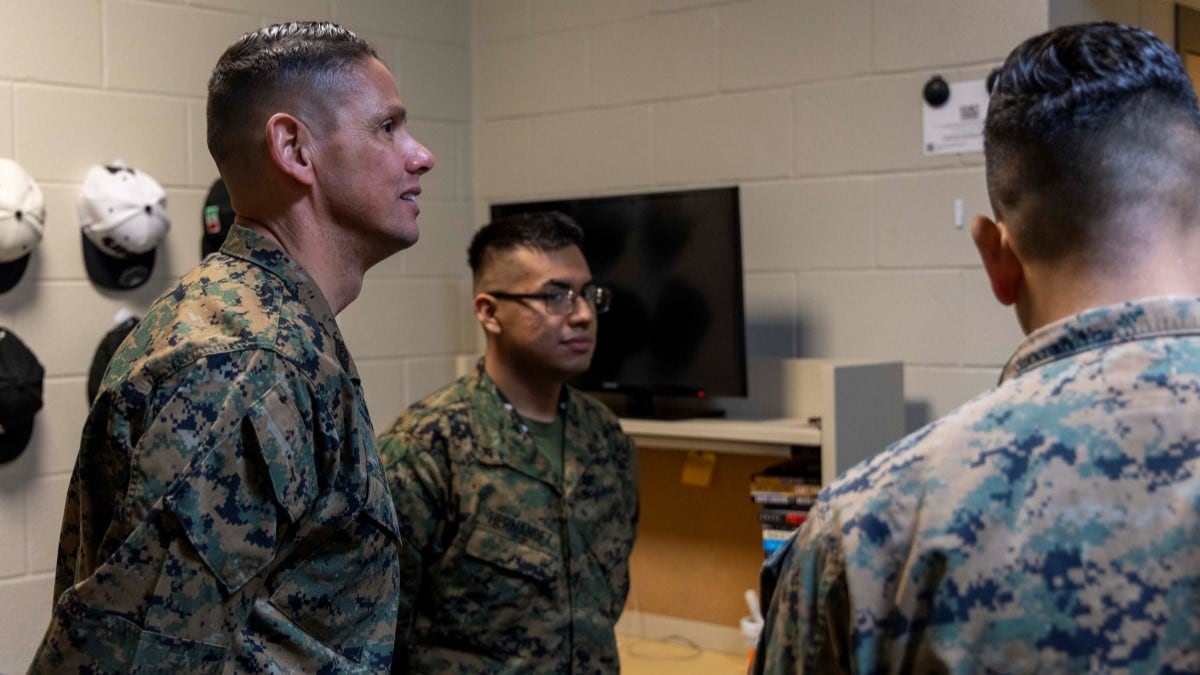

For Houston and the nine other paratroopers who visited the idyllic ski town in January, over the course of a week that delivered a mix of vertigo-inducing fog, blower powder and bluebird views of Glacier National Park, the opportunity to connect with other members of the Battalion was made possible by a small faction of local veterans who for nearly 15 years have been organizing twice-annual retreats to offer military personnel a rare glimpse of civilian life.

According to Frank Kearney, a retired lieutenant general and former deputy commander at United States Special Operations Command, that is precisely the aim of the Whitefish Veterans Support Team, or WVST.

“One of the challenges for young men who get out of the military is that they are seeking a sense of purpose,” Kearney, who lives in Whitefish and was one of the original volunteers to join the nonprofit organization that formed in 2009. “There’s a strong sense of camaraderie that one gains in the military, a sense of belonging to something that is bigger than yourself, and that is something that veterans in general talk a lot about after coming out of the service. It’s difficult to capture in civilian life, especially for these young men who have spent a lot of time in combat zones and have experienced things in a crucible that brought them together as a unit. When they leave the military, they leave that crucible behind. It’s always interesting to give them that similar perspective in a community like Whitefish, where they’re immersed in ski culture and other likeminded veterans. They get that strong sense of camaraderie outside of a war zone.”

WVST is the brainchild of Steve Shea, a West Point Military Academy graduate who conceived of the program 15 years ago while attending a fundraising event for wounded veterans in New York City. Having discovered Whitefish more than two decades ago, Shea believed that the small, intimate and active community held enormous potential to help veterans heal and reintegrate to civilian life, both through outdoor recreation and structured therapy. Two years after conceiving of the idea, Shea partnered with the nationally known Wounded Warrior Project and enlisted help from fellow Whitefish veterans David Trousdale, Larry LaRocque and Kim Richards, who raised enough money to host a dozen injured soldiers for a ski retreat during the 2009 Winter Carnival.

That same year, Kearney, who happened to have coached Shea’s rugby team at West Point, bought a home on Big Mountain and joined the volunteer effort, as did his wife, Betty Sue, whose extensive experience volunteering at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center helped put the visiting soldiers at ease. The organization also found a warm and welcoming reception at Whitefish Mountain Resort, whose majority owner, William Foley, is a 1967 West Point graduate, and encourages the ski area’s use by veteran support groups.

“The mountain has been such a friendly place for us to bring in these airmen and marines and to be able to host these retreats,” Kearney told the Flathead Beacon. “It’s allowed us to give them an opportunity to come together with a local population of veterans and have a conversation with older veterans, to share stories and take some time off, and to talk about their combat experiences and help them transition out of the military. When you have people who are recovering from an injury sustained in combat, or from post-traumatic stress, it’s a huge confidence builder for them to come out here.”

Indeed, the ski area on Big Mountain is rooted in a rich military history, with many of its founders shaping the ski runs upon returning from World War II, where they served in the 10th Mountain Division. To honor that legacy, a 6-foot Jesus statue is situated along a gladed ski run on Big Mountain, reminiscent of the religious shrines the ski area’s founders encountered in the Italian Alps.

For the servicemen who recently visited Whitefish, the opportunity to process their recent combat experience with other veterans in a setting far removed from the base in Fort Bragg, and even further removed from the recent conflict in Afghanistan, was both healing and surreal.

Ian Rowe, 26, said it’s strange to have played a part in concluding a war whose opening salvo began two decades ago with the deployment of America’s oldest millennials. Last August, it was the youngest members of Generation Z who enabled an operation in which military aircraft ferried more than 79,000 civilians away from the Kabul airport, including 6,000 Americans.

RELATED

More than 800,000 American service members and 25,000 civilians served in Afghanistan over the almost 20-year mission. A total of 2,461 U.S. service members and civilians were killed and more than 20,000 were injured.

The casualties included the 13 service members killed in the twin explosions caused by suicide bombers, which Rowe described as unexpected but not surprising.

“We were playing ping pong when it happened,” he said. “We found a table and we were playing when we heart the first explosion. We felt it.”

Rowe, who was born in Chamonix, France, but grew up in New Hampshire and received his undergraduate degree from the University of New Hampshire, plans to return to school after he closes out his current contract with the Army. He’s not yet sure where he’ll attend, but he hopes it’s near a ski resort.

“I could definitely get used to this,” he said.