The number of courts-martial and other severe punishments meted out to misbehaving troops across the military has steadily declined in recent years, raising concerns at the Pentagon’s highest levels that some commanders have gone soft on traditional military discipline.

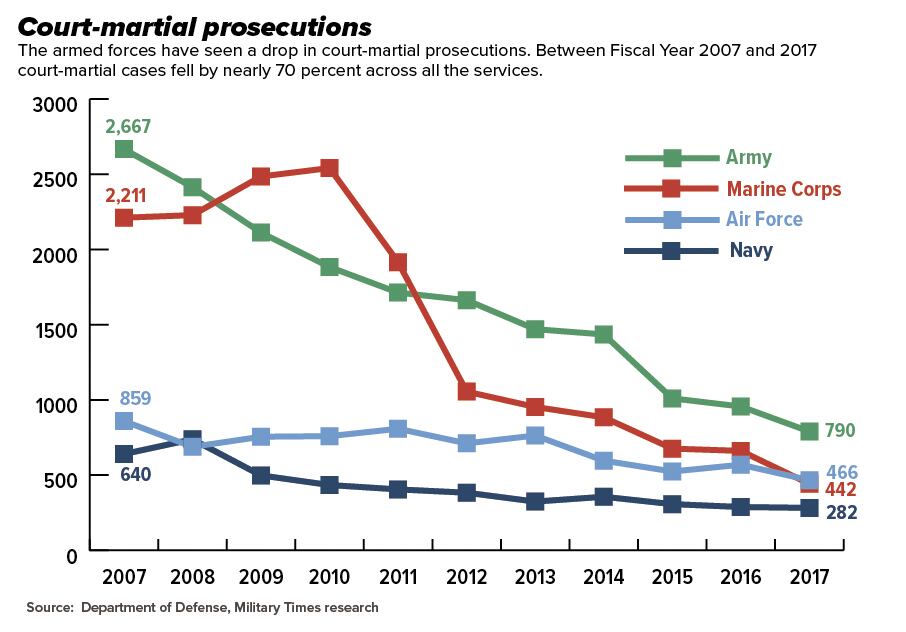

The total of general, special and summary court-martial cases handled by the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines has plummeted by nearly 70 percent during the past decade — down from 6,377 in 2007 to 1,980 in 2017, according to a Military Times analysis.

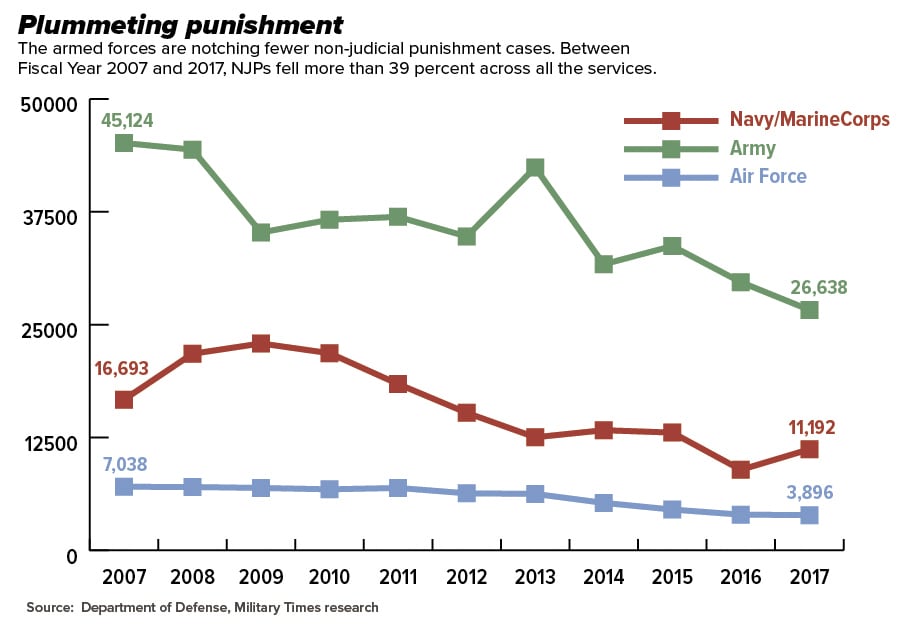

Military Times found that less severe non-judicial punishment cases also tumbled — down nearly 40 percent over the same span.

The dive in Uniform Code of Military Justice enforcement far outpaced the drawdown in overall active-duty troops. Combined end strength of the four services dropped by 14 percent since 2007 to roughly 1.3 million in 2017.

Many military experts believe a primary cause for the falling UCMJ numbers stems from commanders’ decisions to opt against courts-martial proceedings or NJPs and instead lean on administrative discipline, which often results in the accused service member getting kicked out of the military.

Administrative discipline tends to be bureaucratically easier and less time-consuming than traditional UCMJ measures to punish misconduct.

That may explain the highly unusual Aug. 13 memo that Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis fired off, when he voiced concerns that today’s military commanders may be jeopardizing the force’s long-term good order and discipline.

“Leaders must be willing to choose the harder right over the easier wrong,” Mattis wrote in the memo, which was obtained by Military Times.

“Administrative actions should not be the default method to address illicit conduct simply because it is less burdensome than the military justice system.”

The retired four-star Marine general cautioned commanders to never be “so risk-adverse that they lose their focus on forging disciplined troops ready to ferociously and ethically defeat our enemies in the battlefield.”

Pentagon officials declined further comment on the Mattis memo.

“It speaks for itself,” Pentagon spokesman Johnny Michael wrote in an email to Military Times.

“It is general guidance to the Department on the need for discipline within the ranks and is not intended in any way to suggest the outcome of any case or for all cases.”

Neither the Pentagon nor service leaders would speculate about what caused the decade-long drop in disciplinary actions.

But civilian attorneys who specialize in military criminal justice suggested a wide range of reasons for the decline.

Along with a hike in administrative separations, they also suspect the drop might reflect an institutional focus on prosecuting time-consuming sexual assault cases or even a military force that’s less prone to committing crimes.

RELATED

Adseps to the rescue

Military Times could not independently verify whether administrative separations are eating into the number of traditional punishment proceedings.

Those administrative measures are not tracked in the annual UCMJ reports to Congress and only the Marines provided “adsep” data in response to a request from Military Times.

The Marines’ data did not reflect a significant rise in the number of service members who were involuntarily booted from the Corps. That number peaked in 2013 at 10,772 cases before falling to 8,902 in 2017.

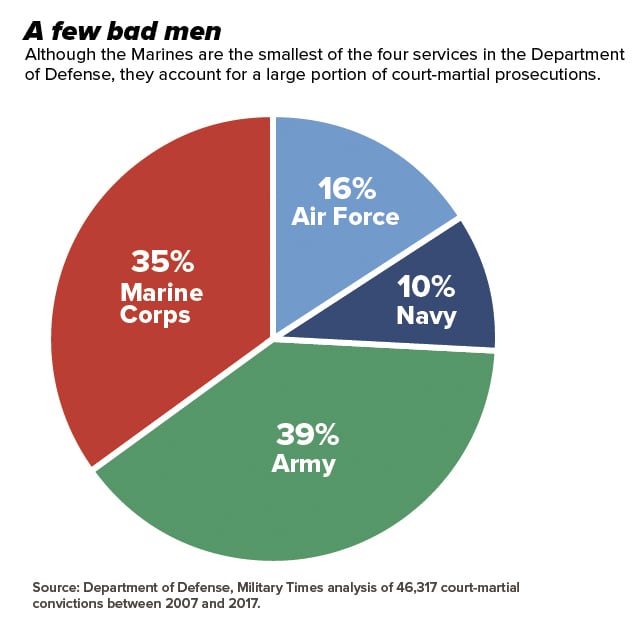

Although the smallest of the four services, the Marines accounted for 35 percent of the military’s total court-martial proceedings over the decade, trailing only the Army at 39 percent.

But Phil Stackhouse, a civilian defense attorney who served 22 years in the Marines, suspects that commanders in the other services might opt for adseps “as a quick method to kick out the service member.”

“I think overall they are trying fewer cases, but it’s because the service members are offering a quick resolution by agreeing to adsep, or the command is using adsep as a quick method to kick out the service member,” Stackhouse said.

Commanding officers must decide whether they want to evict a troublemaker quickly through administrative separation or make an example for other troops by sending the suspect to court-martial, he said.

From a commander’s perspective, administrative discipline is faster than court-martial proceedings, which can hurt the defendant’s unit in a wide number of ways, said Lauren Hanzel, a former Navy attorney now practicing in South Carolina.

“If you’re going to wait six, eight, 12 months for a court-martial to run its course, that service member isn’t usually doing the same job they’ve done before,” she said. “You lose a body for that entire time the court-martial is running its course.”

Joseph Jordan, a former Army prosecutor, said he’s not convinced that adseps should bother Mattis.

“If you have a problem child in your formation, maybe the easiest way to get rid of this problem child and not affect the rest of your good soldiers is to get him out of the service as quickly as possible,” Jordan said.

“Commanders do that. I’m not sure it’s necessarily a problem.”

Recruiting woes and sexual assault

Retired Marine Corps judge Patrick McLain pointed to another possible reason for fewer disciplinary cases: better troops.

A decade ago, Iraq and Afghanistan were hotter counterinsurgency wars that required far more boots on the ground.

A recruiting crunch led the Army and Marine Corps to lower standards, in some cases offering entry waivers to convicted criminals.

“They’ve been able to recruit a force, as years have progressed, that has less indicators or less predictors of misconduct,” McLain said. “You hate to peg people, but the truth is those are indicators of future conduct if you have that kind of stuff in the background.”

Another factor may be Capitol Hill’s pressure on commanders to crack down on sex crimes at the expense of other offenses, including acts of violence.

“There’s such a focus on that offense that I think all the other offenses look less serious,” attorney Hanzel said.

RELATED

Crimes such as insubordination, assault consummated by a battery and false official statements are lower priorities due to the “external pressures of how commanders deal with sexual assault,” she said.

“When certain members of Congress were quite openly saying, ‘if we don’t like the way a particular flag officer is disposing of these cases, we’re not going to concur with their selection to the next rank’ … that had a chilling effect,” McLain added.

To former Air Force attorney Grover Baxley, that raises the question of whether a military criminal justice system already fixated on sex crimes has the capacity to investigate and prosecute a far larger pool of cases.

“The problem is the JAG Corps is right now 100 percent fully worked prosecuting sexual assault cases because that’s the direction they’ve received from Congress,” he said. “Sexual assault prosecution is the number one priority of the JAG Corps. You only have so many prosecutors and so many judges.”

“Given the choice, they’re going to prosecute the sexual assault and let the other stuff fall by the wayside,” Baxley said.

The mind of Mattis

As the Mattis memo ripples through the services, critics wonder if it might backfire.

“It would not surprise me if defense counsel made the secretary’s memorandum the basis for claims of unlawful command influence,” said Eugene Fidell, a UCMJ expert who teaches at Yale University. “Whether such claims, if there are any, will gain traction is another matter.”

Called the “mortal enemy of military justice,” unlawful command influence, or UCI, occurs when senior uniformed or civilian leaders utter words or take actions that wrongfully influence the outcome of court-martial cases, jeopardize the appellate process or undermine the public’s confidence in the armed forces by appearing to tip the scales of justice.

To McLain, Mattis appeared to urge commanders to act more carefully when handling disciplinary cases, but “there’s still always that issue of telling commanders how to dispose of misconduct.”

It’s a concern also raised by the military’s top officer, Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

He told Military Times that commanders “ought to be clear what the standards are that are expected in a unit and not be concerned that that’s undue command influence.”

“Articulating the standards that we are going to hold our men and women [to] is not undue command influence, and you ought to use all the tools that are available to you, because I’m holding you accountable and responsible for the environment within which your men and women are being led,” Dunford said.

The canary in the UCI coal mine might be marijuana cases, Hanzel said.

She pointed out that commanders increasingly have come to rely on administrative actions to deal with pot smokers in the ranks, a tool they might use less often now that the secretary of defense has spoken.

“If we see that happening after the Mattis memo, I think we have maybe more traction on the [unlawful command influence] motions that I see coming,” she said.

Military Times Pentagon Bureau Chief Tara Copp and Senior Reporter Shawn Snow contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story included incorrect numbers in the chart illustrating the decline in courts-martial for the Army. The chart has been corrected.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.