Sgt. Zonia Kotaro had a good first Marine Corps enlistment.

She had gone off to recruit training in 2014, learned the skills of a motor transport operator, and went overseas to her first unit in Okinawa, Japan, where she stayed two years.

In the final part of her tour, she supported training at the School of Infantry-West in Camp Pendleton, California.

She put in a package to re-enlist. She didn’t quite make the cut.

So the Marine shrugged, assuming her time in uniform was over. She gathered her paperwork and stepped into the civilian world, college and a new life.

But a few months later she got a letter.

Oh, right, that Individual Ready Reserve thing, or IRR as most Marines know it. That “obligation” is rarely discussed when eager young recruits sign the dotted line and then stand on yellow footprints.

RELATED

The letter asked her to attend a “muster” of other IRR Marines like her. A little nervous, not knowing exactly what to expect, Kotaro drove to the site in La Jolla, California, close to where she lived, and not far from Camp Pendleton, where she was stationed before she got out.

“When I was in, I did not know anything about IRR,” she told Marine Corps Times. “I just know I’ll be on standby. I knew it was a reserve status.”

But she knew next to nothing about the Marine Corps Reserve. As few Marines do. The Corps has prided itself on getting Marines young and only keeping a handful as it funnels talent into longer career paths.

That funneling, however, is seeing a shift. The Corps wants more experienced leaders in some of its formally overlooked MOSes such as infantry. They want to get good Marines, train them well and keep them longer.

One place that’s helping is the Selected Marine Corps Reserve. And a waystation between active duty and the Reserve is the IRR. Marine leaders are seeing a pool of 60,000 trained and qualified Marines cycling through IRR status each year that could fill out the reserve ranks and even transition between active and reserve status as their life needs and Marine Corps’ needs overlap.

Col. William Chairsell, director of Marine Corps Individual Reserve Support Activity, spoke with Marine Corps Times recently about work they’re doing to tap into the IRR and find Marines who want to continue their service, but in a different capacity.

Marine reserve leaders are looking to that IRR status as a place to pitch themselves as a way for Marines to stay not only connected to the Corps but to start a second life in the Marines with new job opportunities, openings for deployment and low time commitments.

For decades, the IRR meant getting a call once a year for the remainder of a contract. Basically, planners want to know how many IRR Marines are around and what job skills they have in case the Corps needs to call someone up for World War III.

Now, the Marine Corps Reserve is using in-person musters of area IRR Marines in denser population areas as a way to check both the status of those IRR Marines and to highlight what both the IRR and larger reserves have to offer.

For example, Marines can serve in uniform, with no obligation for another contract while on IRR, Chairsell said.

Admittedly, some Marines are a little wary of the musters, he said.

Out of about 60,000 Marines in IRR status each year, only about 5,000 to 7,000 attend the in-person musters, another 30,000 to 40,000 are done via a “phone muster” where a reserve liaison contacts them to check their status and offer more information, he said.

Marines came into musters at San Diego while Chairsell was on inspector instructor duty wearing flip flops, sporting long hair and anything but a regulation shave.

That’s fine.

“We’re not going to knife hand you or anything else,” Chairsell said.

The Marine Reserve is holding two dozen such musters a year all over the country. Commandant Gen. David Berger’s push for better talent management across the total force ― active and reserve ― means more of prioritization for retaining talent however the Corps can do it best, Chairsell said.

You get paid $230 for attending the muster, get a chance to talk to the prior service recruiter and see what your local unit is doing, he said.

One of the best-kept secrets that few in any branch are aware of is that a Marine, sailor, soldier or airman can actually retire from the IRR simply by staying in that status until they reach the retirement time obligation.

Each year in the IRR counts 15 membership points toward retirement. By picking up more points, as much as 35 for standard drills, they can get the 50 points they need each year. Now, Marines won’t collect the reserve retirement until they turn age 60, but it is a benefit, he said.

Those points weren’t quite enough for Kotaro, who bought the pitch at the muster and now serves on the active reserves as a career planner, a precise fit with her human resources undergraduate degree.

And the IRR push is not limited to the enlisted.

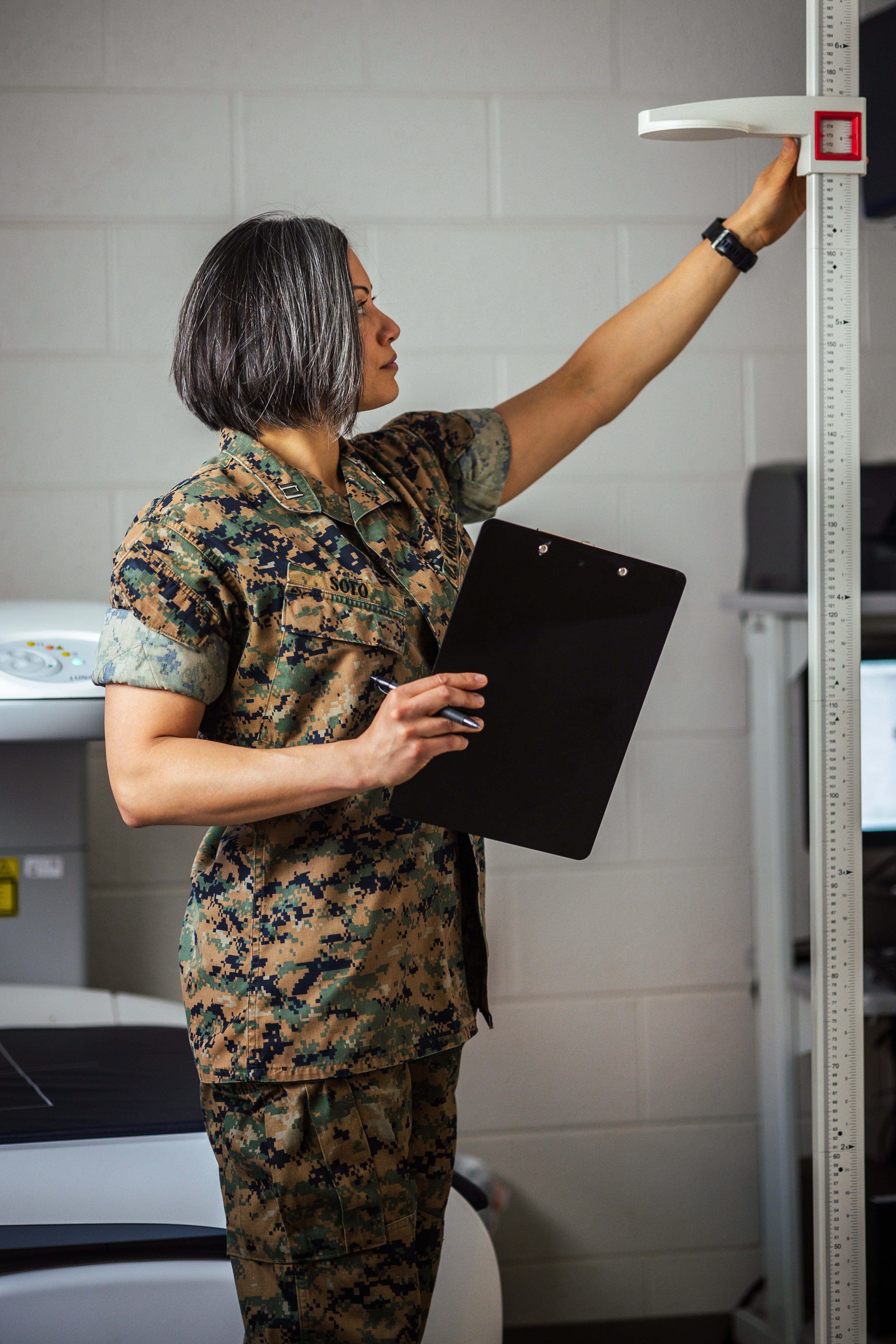

Capt. Lara Soto told Marine Corps Times she started her Marine Corps journey in 2011 on an active duty contract but with the beginnings of a family and a growing small business back home she took a detour, going to the reserves in her officer obligation out of The Basic School.

She loved the experience, working with a small detachment of communications Marines on Grissom Air Force Reserve Base, Indiana.

With two young children she decided to go into IRR status once she had the opportunity. Though she had a little time left to fill on her reserve contract, she felt she was leaving on “a high note.”

But man, did she miss working with Marines.

Chairsell said that those Marines on IRR are considered “non-obligators” meaning they can attend drills, get paid and do their job or something equivalent. It’s only once they take on an additional MOS training that they would be required to sign a new reserve contract.

Like Kotaro, the captain didn’t know a lot about IRR but found out a lot when she went to her own muster.

“I was excited to see the Marines,” she said. “I’d been out of the Marine Corps and away from Marines, it was a refreshing sight. It was very informative, there was no pressure to join or get back in, basically the people you needed to speak to were available there if you were interested.”

From there she slotted into the Individual Marine Augmentee program, a little-known program that puts Marines in an active status to assist units with backfills or manpower strains.

That duty saw her travel all over the Midwest going to musters to talk to Marines about using their IRR status or sampling one of the many flavors of reserve duties.

She was slated to go to Korea for a training exercise, though that was pulled when events got canceled due to the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Recently she’s been assigned to Marine Corps Base-Quantico, Virginia, working in IMA status to help with the Training and Education Command on a body composition study.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.