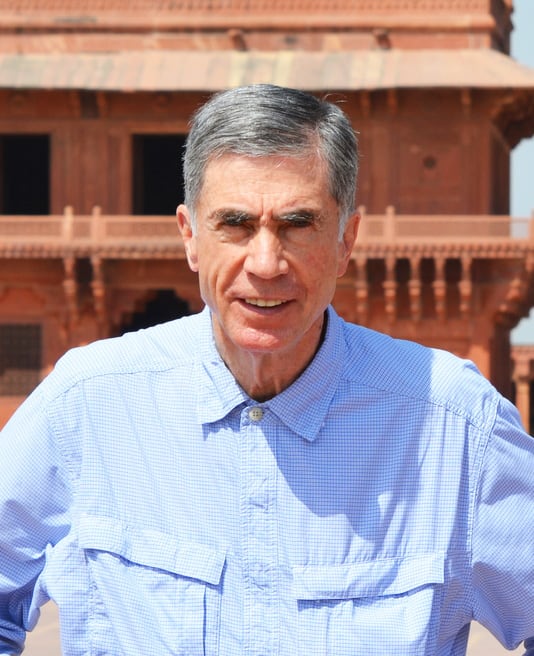

Chuck Robb was once governor of Virginia and a U.S. senator. But before those high offices, he sought a different title: Marine Corps officer.

It was during that period of his life he served as a White House aide, marrying President Lyndon B. Johnson’s daughter and led a company of Marines in combat Vietnam.

And despite decades of public life and now another life in retirement, the octogenarian starts and ends his new memoir with his time in uniform.

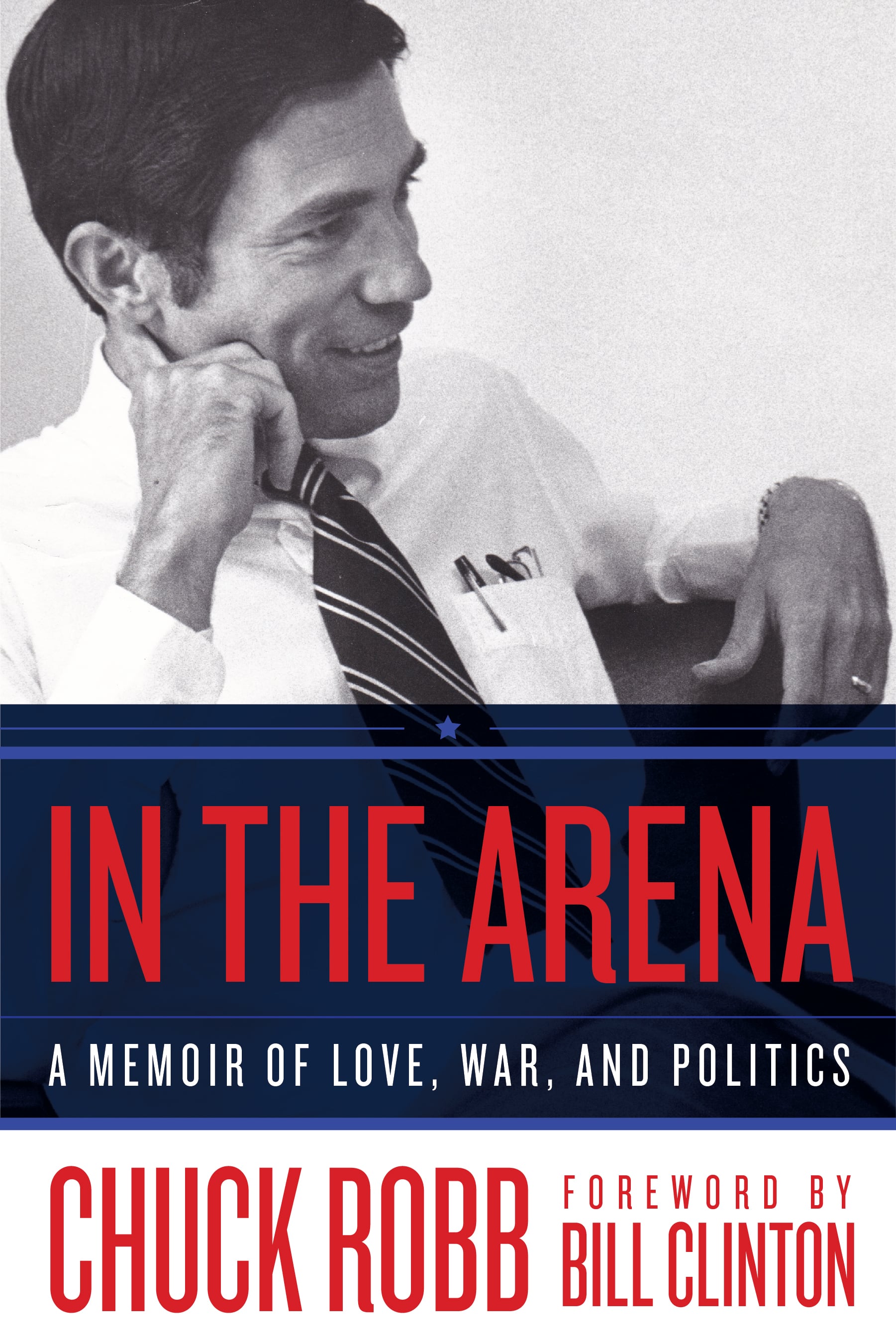

The book, “In the Arena: A memoir of love, war and politics” rolls through Robb’s life from childhood to his leaving politics.

He drew the book title from President Theodore Roosevelt, “It is not the critic who counts; not the main how points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena.”

The former senator served on active duty in the Marine Corps from 1960–1970, rising to the rank of major.

Robb talked recently with Marine Corps Times about his life in service, his new book and what he hopes to share with others, especially Marines, about his experiences.

*The following Q&A section has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Will you share with readers why you chose the Marine Corps and how you became a Marine Corps officer?

A: I always expected to go into the service. In college, you were required to sign up for Reserve Officer Training Corps, out of the three services the Navy option looked more squared away but the Marines seemed to take a little extra effort to make sure they got it right and looked as sharp as they could.

I had signed up for the U.S. Naval Academy but wasn’t accepted until after my freshman year and I was already in ROTC. I didn’t want to start college over at the academy so I opted for the NROTC route. A Marine major in the program had a no-nonsense way of selling the program, ‘If you think you’re tough enough to join our ranks, then prove it.”

Q: What are some of your most significant memories from Officer Candidate School and The Basic School?

A: There were a series of tests for small unit training. But the most memorable was the “Hill Trail.” It was a physical test shared by every Marine officer candidate in that era — a grueling march through a heavily wooded area on a rocky trail that tested our strength, endurance and ability to gut it out while struggling up and down steep hills carrying full combat gear: a rifle, helmet, field pack and two full canteens. There were serious injuries in the regiment during training, one death, one critically injured and one who ended up in a coma.

Q: Early in your officer career you served as an aide to various senior leaders, at the Marine Barracks Washington and as an aide to the president. But you sought a combat tour in Vietnam though you could have avoided it. Why was that important to you?

A: Yes, I was grateful for each of the plum assignments I’d been given in my then-six years on active duty, but I had repeatedly requested a combat assignment and felt like I’d be shirking my responsibility if I let this opportunity pass me by.

Most of the Marines I’d trained and served with had, by then, already been to Vietnam. A few of them were on their second tour of duty. It was my own sense, particularly if I didn’t stay any longer than I was obligated to in the Corps that I do duty with the “muddy boot” Marines in addition to the “spit and polish Marines.”

Many of those decisions were based on core values that I learned as a young Marine officer. One of the most important was that respect is an essential element of leadership. The key to getting people to follow your orders, whether those orders were to march in a parade or to risk their lives taking a heavily enemy-fortified hill, is to first develop respect.”

— "In the Arena: A memoir of love, war and politics," by Chuck Robb

Q: Your 13 months as a company commander in Vietnam in 1968 surely had its share of experiences. You’re fairly blunt about some of the more personal episodes you faced in the book, do you care to share more with readers?

A: There was a Marine who’d been disciplined for poor behavior only a few days before who deliberately stood up in a firefight, exposing himself to enemy fire to draw attention from the enemy gunner. He was cut down by AK-47 fire. In May 1968, 2nd Lt. Terry Hale, a likable and gung ho University of Texas graduate went with my company on his very first operation in the bush and was killed by a Viet Cong booby trap. Pale and still in an unzipped black rubber bag, Terry Hale was laid out for identification. It is not something one forgets. The astringent smell stayed in my nostrils long after I left the tent.

Within a few days, a replacement for Lt. Hill arrived at Hill 65. One staff sergeant, who was then the acting platoon commander, had a malfunctioning M16 rifle. He wrote a letter to the manufacturer who sent him a replacement direct to Vietnam. He was proud of that. A week after he got the rifle we were on a night movement, just a little moonlight in the trees. We were spread out moving through dense vegetation. The staff sergeant hit a tripwire, triggering an unexploded, captured U.S. 105mm round that was hidden in a hedgerow.

I happened to be closest to him when the shell exploded but just far enough to avoid being hit. I called in a medevac helicopter and carried him with another Marine to a cleared road. I could hear the gurgle in his throat as he struggled to breathe. We hurried to the helo but the sounds he made became fainter and fainter. By the time we reached the thumping chopper, he was silent.

The staff sergeant was the first of two Marines who would die in my arms during my thirteen months in Vietnam. There was no fanfare or extraordinary drama to it; the life simply slipped from his body.

Q: The period during the Vietnam War and its aftermath were some of the most politically contentious times in U.S. history. How did you navigate your service and the war’s impact on the nation as you later pursued a political career?

A: At that time the only way most people looked at military service in Vietnam was how to get out of service in Vietnam. Immediately after I returned from Vietnam I served as a representative of the Platoon Leaders Class program, speaking on college campuses about how students could become Marine officers. I could communicate reasonably effectively and always sought to understand any opposition. So, I read an anti-war book, “The Greening of America,” by Charles Reich, to better understand the other side of the argument, which is still what I recommend people do.

During one event a student shouted, “You are teaching people to kill. What does that have to do with pacification?” I responded, “Most people know how to kill already. We don’t have to teach them that.” I also said that I didn’t like being engaged in war and found nothing satisfying about it. The dialogue surprised some students. At the very least, I hoped to give them a sense that I, like other returning veterans, was not an automaton or a warmonger but a human being, not so different from any of them and fully capable of developing personal opinions. I don’t know if I changed anybody’s stance on the war that day, but by the time I finished, the audience gave me a standing ovation.

Q: During your time as a U.S. senator, you served on various committees and groups with direct links to military and veterans affairs. One included the formation of the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy under President Clinton to allow for homosexual people to continue to serve in the military. Looking back on that time, can you share with readers why that was important for you?

A: The first time I became more aware of how acute the problem and the need for DADT was after the military in law school. During a clerkship, I kept officer qualification records for those who’d been disciplined in the Marines. I found two majors, and I was a major by that point, who had performed well in combat but they were accused of being homosexuals and were going to be discharged. Not for their conduct but over the accusations. I said, you know, “This is wrong.” That was my first direct experience.

Q: You served on committees that took you back to Vietnam and to neighboring countries. What was it like to return to Vietnam years later?

A: It’s an interesting experience to talk to people on the other side of combat. While I was there I was taken out to some of the areas where I had fought. Then afterward when I met with many of the now-former Viet Cong for the most part, we didn’t have many meetings with the North Vietnamese Army officials at that point, but you could talk to them and in effect acknowledge yes we fought on opposite sides of the war and we’re now at peace. It was also clear at that point they were a little reluctant still to talk too much to a foreign dignitary. You can’t get that experience any other way than to have been in combat and then to have a chance to talk to some of the people who were trying to kill you.

Q: Much later in your career you served on the Iraq Study Group and the Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission. How did your military experience help you with that work?

A: There is no question in my mind that you gain an amount of credibility if you’ve been there. If you’re talking about war, if you have been involved in combat, most of your peers will allow you a certain leeway because you’ve been there on the ground and are willing to put your life on the line. And you know if you’re going to suggest certain types of activities you know what else is involved.

Q: You end the book with a reference to an early challenge in officer training. Why did you make that choice as an author?

A: It made a nice way to close it so that people could understand your visceral feelings, especially the challenge to do your best, particularly when you’re being evaluated in direct competition with all of the other peers who are the same rank. And you’re able to deliver the goods.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.