Human factors triggered by lapses in supervision and a lack of proper driver training have been the leading causes of tactical vehicle mishaps for roughly a decade, according to a new congressional watchdog report released Wednesday.

From 2010 to 2019, the Army and Marine Corps had a combined 3,753 tactical vehicle mishaps that resulted in 123 service member deaths, a report by the Government Accountability Office stated.

The GAO study looked at those accidents, along with the training, procedures and range safety methods for three Marines bases, 11 Marine battalions, six Army bases and nine Army brigades.

The study was conducted at the request of Congress after a spate of high-profile rollover deaths caused several grieving families to demand action.

“I think the GAO report was essential, as a starting point,” Michael H. C. McDowell said.

RELATED

McDowell is the father of Marine 1st Lt. Hugh Conor McDowell, 24, who died in 2019 when the light armored vehicle he was commanding rolled over during a training exercise in Camp Pendleton, California.

Rollovers, though only accounting for 24 percent of all accidents, were the deadliest form of tactical vehicle accident, accounting for more than 63 percent of accidents where a service member died, according to the report.

A good starting point

“We have a responsibility to ensure the young men and women who wear the uniform are properly trained and supervised to avoid preventable accidents. It’s clear the Army and Marine Corps have deficiencies in their practices to mitigate these tactical vehicle accidents,” Rep. Anthony Brown, D-Marylan, told Military Times.

“This must be addressed to prevent future tragedies. This report is only the beginning of our efforts,” Brown said in a statement.

The report gave a total of nine recommendations, including that both services conduct a review of their training and licensing standards to ensure they are implemented more consistently, as well as ensure each service has enough safety officers with enough resources to successfully perform their jobs.

The GAO also recommended that the services create a forum for range safety personnel to share information and best practices across facilities and across the services.

An Army spokesperson, Jason Waggoner, said that the service has already implemented this recommendation.

“The Marine Corps has reviewed and concurred with the recommendations of the GAO report. In addition to improving our reporting culture and reporting mechanisms, the Marine Corps has a multi-front campaign to improve the operational capability of our tactical vehicle fleet,” Capt. Andrew Wood, a Corps spokesman told Marine Corps Times on Wednesday.

“From initial design and acquisition, to recruiting and training, and information sharing with our DoD partners we are making every effort to reduce our mishap rate,” he added.

Cary Russell, director of defense capability and management with the GAO said both services concurring with the recommendations was a good start.

“I think there is an intent there to implement (the recommendations). We will just have to see,” he said.

Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee Rep. John Garamendi demanded that the two services follow every single recommendation by the GAO.

“The report that GAO released today highlights a troubling pattern of training shortfalls and supervision lapses that have led to a concerning rise in preventable training deaths throughout the military. My message to military leadership is clear: this will not be tolerated,” the California Democrat said in a press release.

“I will continue to conduct robust oversight into this matter to ensure the GAO policy recommendations are implemented and military leadership transforms its culture of neglect into a culture of safety,” he added.

McDowell said the report was a good starting point, but called on the recommendations to be strengthened, particularly when it comes to improving range safety and how officials at those ranges communicate hazards to units.

Of the nine total bases the GAO looked at, only four required units to rehearse their movements prior to training commencing.

“The training range officials generally believed it was the duty of the unit leadership to manage the risk to their unit in higher risk situations like night exercises or blackout conditions,” the report said.

“However, in multiple interviews with tactical vehicle drivers, they identified night operations as challenging and riskier than normal operations, and drivers also shared that they performed night operations without rehearsals and felt it was dangerous,” the report added.

Accidents on the home front

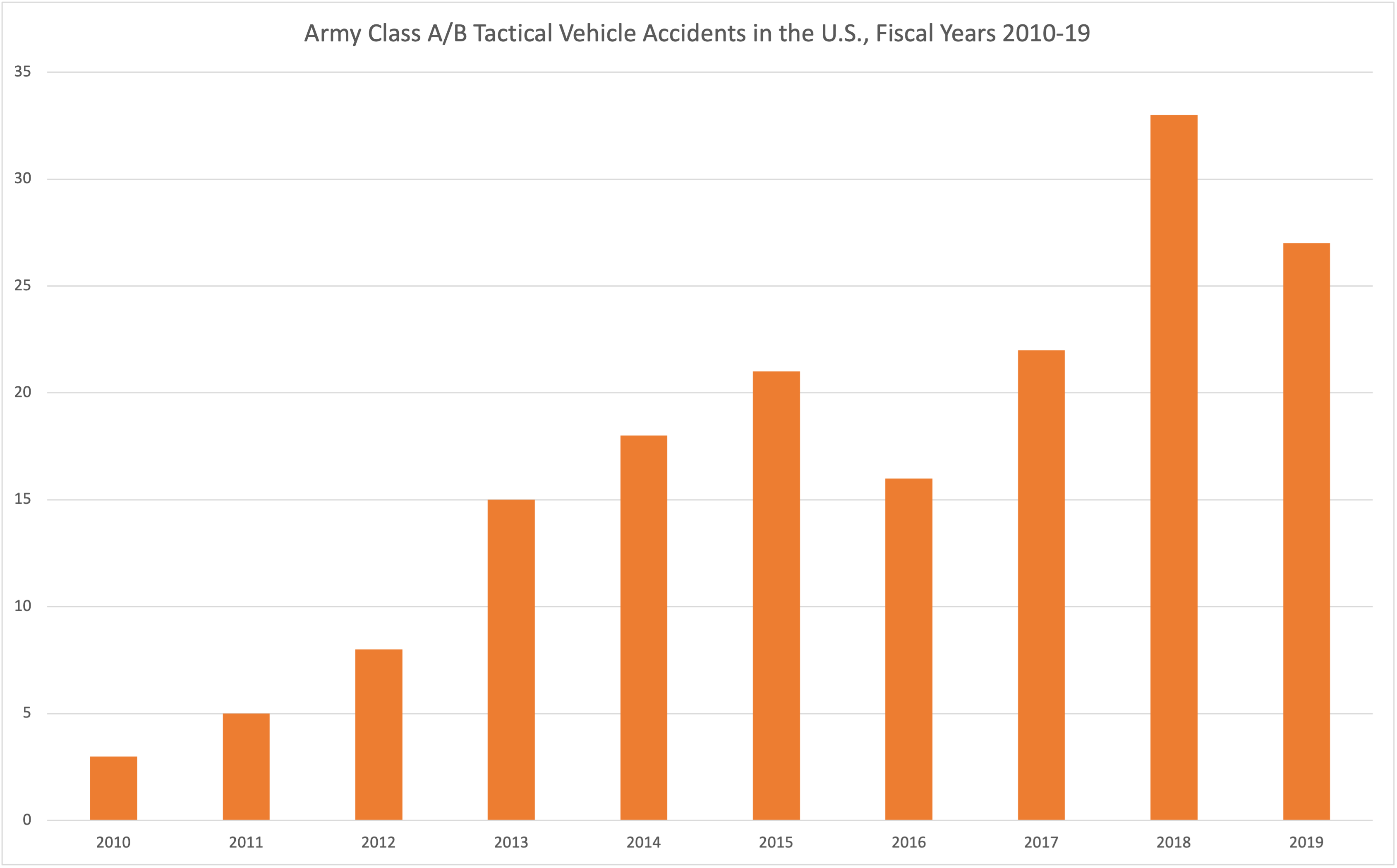

The report’s data reveals some worrisome trends in accidents for the Army.

Although the number of Class A and B mishaps involving Army tactical vehicles has decreased since fiscal year 2010, the number that have occurred on U.S. soil have increased dramatically.

Class A accidents result in either death or permanent disability, or more than $2 million in damages. Class B accidents cause either permanent partial disability, inpatient hospital care for three or more people, or damages above $500,000 that don’t constitute a Class A accident.

In the U.S. during fiscal year 2010, there were three Army Class A or B accidents.

But by fiscal 2015, that number had jumped to 21.

The stateside accidents peaked at 33 in 2018.

For the Marine Corps accidents within the U.S. have remained relatively steady.

In 2010, three of its Class A and B mishaps happened within the U.S., while in 2019 that number only rose to four.

However, with the war in Afghanistan coming to a close, a higher portion of Marine Corps accidents have happened in the U.S.

In 2012, there were six Class A and B mishaps in Afghanistan, but the final mishap reported in the country took place in 2014.

Short on safety officers

The investigation by the GAO found that the Marine Corps only had one full-time safety officer per division.

At most lower level units, the role of safety officer is assigned to a Marine as an extra duty, leaving them little time to perform the role of safety promotion, and spot checking safety practices within the unit.

“According to one senior Marine Corps safety official we spoke with, unit-level safety officers may have one hour a day to devote to safety matters,” GAO officials wrote.

In 2019, 45 percent of Marines surveyed by the GAO said they were not aware that their unit even had a safety officer.

Citing officials from the Commandant of the Marine Corps Safety Division, the report said that only 60 percent to 70 percent of safety positions throughout the Corps are actually filled.

The Army is also experiencing a severe shortage in safety officers.

“The study identified a need for 298 additional safety and occupational health personnel,” the report reads.

Though 150 positions have been added to operational units, brigades still have “at most one assigned, full-time safety professional to manage the safety program elements of these large, complex and high-risk organizations that often include up to 4,500 assigned soldiers,” the report reads.

“In terms of understanding safety and emphasizing that safety and providing information on safety management — all that is limited when you don’t have enough safety officers,” Russell said.

Shortcutting training

The report highlighted both services’ decentralized driver’s training model as a potential factor in accidents.

“Inexperience or lack of training” accounted for 73 percent of the Army’s Class A accidents, according to the report.

GAO officials concluded that the Army regulation governing driver’s training is not consistently implemented across units and that training was frequently condensed and provided soldiers with limited exposure to diverse conditions, such as varied terrain or driving at night.

Currently, the Army manages vehicle licenses at the unit level, employing certified master drivers to train soldiers to operate tactical vehicles.

RELATED

Young soldier’s training death ‘very preventable,’ requires immediate reforms, lawmaker tells SECDEF

The Marine Corps, by comparison, has dedicated positions for certain tactical vehicle drivers and trains them at dedicated training units.

Every Army master driver interviewed by investigators said they had to shorten or break up training programs designed to take place over the course of 5-10 consecutive days, according to the report.

“Driver’s training is not a high priority for the units, and it’s never an issue until it becomes an issue,” said one master driver.

“The Army is trying to implement safety through paperwork instead of action,” noted another master driver. “A piece of paper is not going to make drivers safer on the road.”

The Army and the Defense Department defended the Army’s driver’s training program in its official response to the GAO report, saying that the Army’s regulations establish a well-defined, phased system of training.

The GAO disagreed, saying that the training program differed from “how the Army conducts other types of military training” because it didn’t have any “performance criteria and measurable standards” to train drivers beyond an initial road test.

That lack of measurable standards leaves the training programs “vulnerable to competing with other unit priorities,” GAO officials argue in the report. “We continue to believe that by developing performance criteria and measurable standards for driver training, the Army would better ensure that its drivers have the skills that are needed to operate vehicles safely and effectively under diverse driving conditions.”

When reached by Military Times, the Army claimed it had already checked the box and implemented the GAO’s recommendation to implement “specific performance criteria and measurable standards” for licensing drivers.

But the regulation governing driver’s training hasn’t been updated since 2019, and a publicly available list of Army Directives did not include any updates to licensing standards.

“The Army concurs with the GAO’s recommendations, which will lead to improved vehicle driver training and risk management,” said Waggoner, the Army spokesperson, in an emailed statement. “The Army is in the process of implementing the recommendations and has already implemented two in our ongoing effort to prevent loss and sustain combat readiness.”

The Army did not immediately respond to a follow-up question asking it to specify how — or if — it had implemented reforms to its drivers training program in accordance with the GAO’s recommendation.

Though the Marine Corps does have dedicated motor transport operators, many Marines with jobs unrelated to driving tactical vehicles receive “incidental licenses” to fill out vacant driving positions once they are in the fleet.

The GAO found several issues with the consistency of the licensing program in the Corps, along with issues of follow up training.

“According to Marine Corps personnel, licensing programs differed in the amount of practical road time they provided and offered limited opportunities to drive in diverse conditions,” the report said.

During the time period of the study the Marine Corps had minimum mileage requirements to be licensed to drive HMMVs and tactical trucks.

However, four groups of motor transport chiefs in charge of driver training described four different mileage requirements ranging from 45 miles to 125 miles when they were interviewed by GAO investigators.

The licensing process during the time period also lacked the diverse driving environment to fully train a Marine for the field.

“With the old mileage-based training requirement, quality suffered,” one individual identified as a training expert told the GAO.

“Drivers would just run laps around the installation to meet the training requirement; they called it the Camp Lejeune 500,” the Marine added.

In 2020 the Marine Corps scrapped the mileage-based requirements for licensing, giving individual units more control over the licensing procedures.

“Anything you make less structured or less requiring is always a concern,” Russell said.

He did note that if the Marine Corps does actually create a performance based evaluation, they may end up with more proficient drivers.

“The Marine Corps has taken some steps to address the lack of performance criteria and measurable standards in the licensing manual,” the report reads.

Training issues for Marine drivers continued after Marines received their license.

Only one Marine said there were enough opportunities to build driving skills after they received their license. The issue was amplified in the two support and logistic battalions the GAO interviewed.

Those battalions have significantly less training opportunities than that of their counterparts in infantry, reconnaissance or the light armored reconnaissance battalions, who GAO investigators met with.

“Operators who have experience get called on to do the missions and others fall by the wayside,” one Marine in a logistics and support battalion told the GAO.

Russell said if the service made time to train Marines on tactical vehicles like they do on the rifle range, time could be found to ensure the vehicles are operated safely.

“You have to have the time to train on the gun and you have a regimented process to do it,” Russell said.

“Right now there is no requirement that a certain amount of training... and they are shortcutting training efforts,” he added.

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.