Top brass within the ranks of East Coast-based Marines have been looking for the past few years beyond the Marine Expeditionary Unit and toward what it will take to put an entire Marine Expeditionary Force into a fight in Europe.

It’s a leap from how the Corps has been operating in recent decades — where one of the largest units that has been sent to theater was when I MEF and 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade landed in Kuwait for the 2003 Iraq invasion.

Since then, most rotations to combat zones have been at the MEU or even smaller Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force level.

The former II MEF commander, Lt. Gen. Robert F. Hedelund, and some of his subordinate commanders spoke with Marine Corps Times recently to explain what has motivated them to return to MEF-level warfighting and how that will affect Marine training and future deployments.

In June, Hedelund went on to run Marine Corps Forces Command, which handles both active and reserve force generation. Lt. Gen. Brian D. Beaudreault is now the II MEF commanding general.

To the Marines of II Marine Expeditionary Force, most of their training and deployments might look similar to what they’ve been doing for years. But this time, it will be at a higher level that Marine leaders will put the pieces of the force together and employ them across the Atlantic.

It’s a major shift in warfighting and a way to keep adversaries such as Russia always looking over its shoulder.

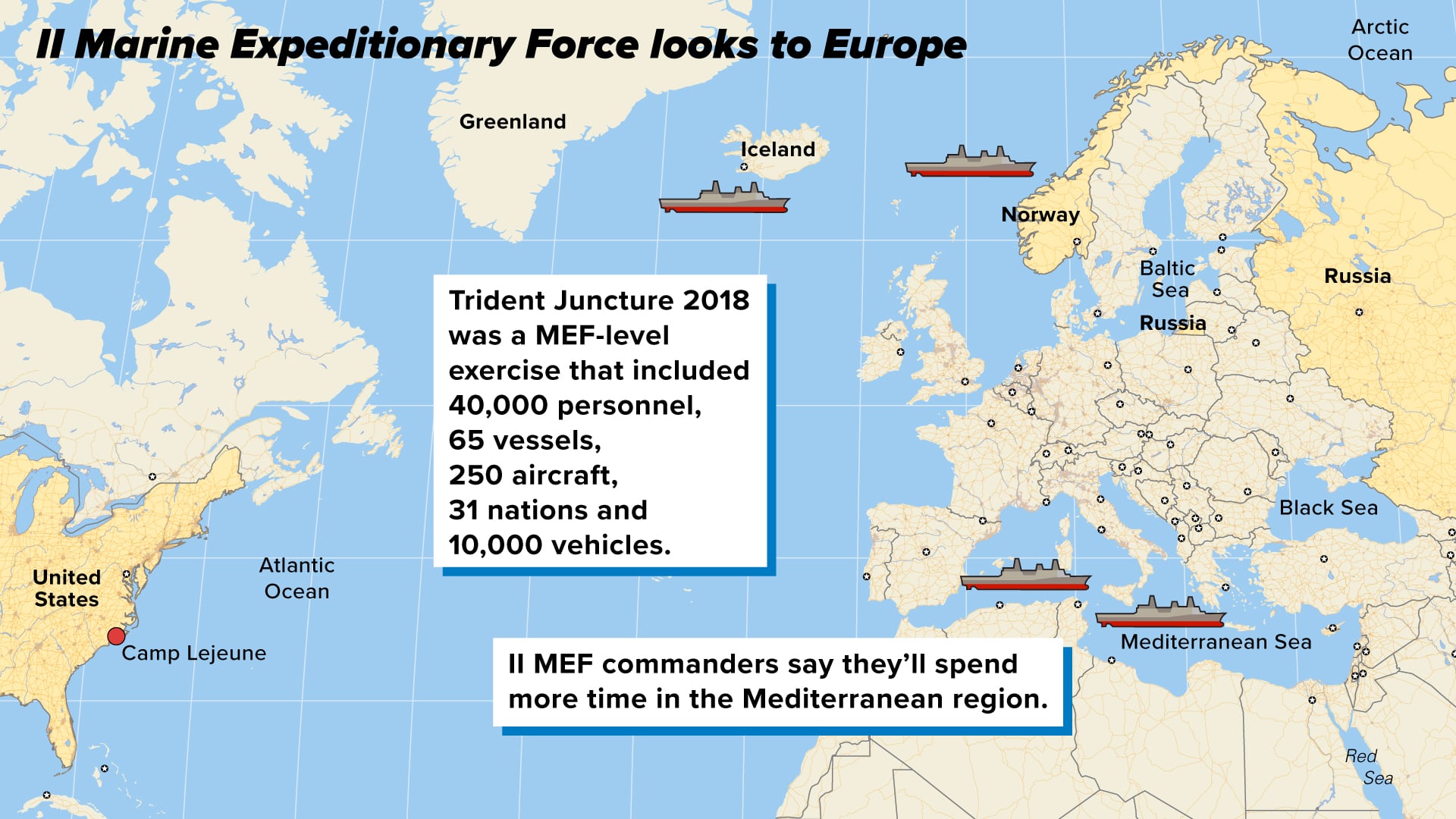

The shift started soon after Hedelund took over at II MEF and took real effect in 2018’s Trident Juncture exercise that took place in Norway.

Before then, II MEF would generate forces for the fight but was not expected to go to war as a unit, he said.

That exercise included more than two dozen nations and an estimated 8,000 Marines participating. While that may seem substantial, equal to nearly four MEUs, it is a little more than half of the 14,500 Marines that make up a MEB and a fraction of the approximately 40,000 Marines in the MEF.

And that’s what will be needed should North Carolina Marines get the call they are needed to counter and harass Russian aggression in the Baltics, Ukraine or elsewhere.

That kind of fight requires vastly different tactics than what most combat-tested Marines have seen in the recent wars against terrorist or insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Both in training and in reality, the MEF will act much like the MEU, Hedelund said. It will run disaggregated but then be able to quickly aggregate or come together to provide maximum force at the point of need.

That’s because the quantity of capabilities provided by the MEF bring its own kind of quality. In a briefing Hedelund presented early in his tenure he explained the range of military operations go from theater security at the special purpose MAGTF level up the joint forcible entry abilities that the MEF can provide.

That’s exactly what the Corps would be needed for, in their own amphibious way, should such a scenario go down.

“We can be at sea, a naval contingent or smaller, in more than one place,” Hedelund said.

That can “make the adversary nervous,” especially in situations short of major combat operations. It gives the United States a way to dislodge enemy units from areas on the battlefield.

That edge fighting provides space for the Army and allies to get into position and build land power and mass needed to push back any invasion or land grabs from Russia or other adversaries.

But to provide the capability, Marine leaders must plan, and train, for it.

The ‘warfighting’ MEF

The shift back to MEF warfighting is unique to II MEF, mostly because Marine leadership has viewed the I MEF for decades as the “warfighting MEF,” focused on CENTCOM.

Newly instated Commandant Gen. David H. Berger’s July planning guidance document clearly spells out that III MEF will be the focus of deterring aggression in the Pacific, while I MEF will support the Indo-Pacific theater requirements and II MEF will undergo “substantial changes” to better align with both Navy 2nd and 6th Fleets with a focus on Europe.

Berger has a MEF-level resume for the near-peer fight, retired Marine Lt. Col. Dakota Wood, a senior research fellow for the Heritage Foundation, told Marine Corps Times. The new commandant’s time as I MEF commander in the Pacific working with sea power and maritime operations as important elements in any potential fight with China could hint at his understanding of MEF war fighting needs.

But, new developments across the Corps and guidance from the previous commandant are helping II MEF build back its own methods for large-scale warfighting. It has shifted it from its third priority to No. 1 starting this year through 2023, according to Marine Corps planning documents.

Some of what is helping the transition from more manageable-sized MEUs stretched across multiple combatant commands to scaling up thinking for having 40,000 Marines at the ready is the creation and use of the MEF Information Groups, or MIGs, Hedelund said.

And that will look different in different commands.

“We shouldn’t strive to be I MEF, III MEF, they’re custom built to tackle those problems,” Hedelund said.

The newly constituted groups duties include keeping the MEF commanding general apprised of the command and control networks, cyber operations and electromagnetic spectrum capabilities and threats.

Col. Jordan Walzer, commanding officer of II MEF MIG, agreed that the new unit has helped synchronize the way the Corps uses information in war fighting, and how the MEF plans for and executes operations, but he emphasized that the underlying work of the MIG can be compared to ancient ways of fighting.

That can be distilling into the single image of a torch.

Walzer told Marine Corps Times a way to think of how information in pre-combat, “gray zone” areas, those just below the level of major warfare, is much like what warlord Genghis Khan had his soldiers do.

The commander ordered his troops to carry two torches at night, that way enemy observers would think the force the faced was twice the size of the actual army.

“It’s not about the act of lighting that torch, it’s understanding the cognitive effect,” Walzer said.

And Walzer’s former three-star boss, Hedelund, praised how the MIG has contributed to the II MEF shift to warfighting.

“The MIG has already paid for itself,” Hedelund said.

The unit broke down silos between intelligence, information, cyber and electronic warfare areas.

Those all used to work in highly compartmentalized cylinders and are now talking to each other, he said.

And that is continuing to evolve, Hedelund said. Marines arriving at II MEF need to make the MIG one of their first stops to “get their head around what’s going on in the MEF,” he said.

Hedelund’s then operations chief, Col. Christian Cabaniss, said: “Everything we do is an operation in the information environment. Short of war it is about demonstrating combat credibility to our potential adversaries across all the war fighting functions.”

And that’s a space in which the Marines see themselves setting the stage, or “shaping” the various battlefield domains beneath the level of armed conflict simply by showing adversaries they have the ability to push a MEF into the fight when needed.

While information informs, it’s the logistics that actually moves manpower and equipment to the fight.

“People confuse exercises as tanks and (light armored vehicles) doing exercises,” Cabaniss said. “The real cost of admission, the real exercise is the logistical element, moving things out of caves and moving stuff around.”

On that end, Brig. Gen. Kevin Stewart, commander of the II MEF Marine Logistics Group, said the way they practice their art of supplying the forward forces has undergone its own changes when planning for MEF-level conflict.

“I think logistics will be the pacing function of the Marine Corps,” Stewart said.

And part of that will include applying big data analytics to the vast amount of information that the Corps has on its equipment and supply needs. Everything from gear maintenance history to fuel consumption rates funnel into planning for large-scale expeditionary operations.

Stewart zeroed in on three things that his and other MEF-level logistician planners are doing. That includes enabling global logistics awareness, basically what they have or need and how to get it to where it’s needed most, diversifying the distribution, or finding new or novel platforms to deliver what the war fighters need and improving sustainment, having operational-level integration between the suppliers and users.

Back to the future

It’s not an entirely new concept, said Cabaniss, commander of II MEF’s operations.

“What’s changed is the recognition of a re-emergence of a great power competition,” Cabaniss said.

The 29-year infantry Marine veteran reflected on similar training he did in the ‘90s when Russia was considered a real threat.

That was the Cold War planning that Marines post-Vietnam and into the early 1990s experienced: large-scale forces at the ready or multiple MEUs being in a theater or working with the geographically-specified fleet in that area.

“To a young rifleman, nothing’s changed,” the colonel said. “We still do many of the same things, tried and true training events they’ve always done.”

Even on the air wing side, Cabaniss said, they’re still training to the same readiness standards except now they might prioritize more near-peer scenarios such as more ground-air integration and dropping bombs.

Where the change is happening is at the headquarters level and a refocus on integration with the Navy.

“It requires the MEF to interact with naval, joint and national capabilities,” Cabaniss said. “So, it is really just a question of scale.”

In fact, both I MEF on the West Coast and III MEF in Okinawa, Japan, have continued to plan and train for force-level war fighting functions. It was I MEF that sent four regiments and at least three enabling battalions into the 2003 Iraq invasion.

But with a host of threats across the globe facing the Corps, from Russia in Europe to China and North Korea in the Pacific and Iran in the Middle East, not to mention ongoing contingency operations and advise-assist commitments in places such as Afghanistan and Africa, the Marine Corps may not be able to afford to send the entire Corps into the fight.

That’s why II MEF’s shift to large-scale operations puts them in a Europe-focused mindset. And moves beyond the Marine Corps have been made to help the Marines get there.

The Navy re-established 2nd Fleet in August 2018 explicitly to patrol the Atlantic after the fleet had been disbanded in 2011. Part of its direction, then Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said at the time, was to play, “a central role in pioneering new and experimental concepts of operation.”

The 2018 Trident Juncture exercise saw a mass of 40,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines float across the Atlantic and pull weapons systems and vehicles from caves in Norway, just as II MEF would have to do in a real-world situation.

But while valuable, Hedelund, Cabaniss and others said that type of training won’t be the norm. It’s too expensive and consumes too many resources.

“That is a huge challenge,” Hedelund said. “While we have opportunities out there, we have to pick the ones we get the most out of.”

But to continue to work the MEF-level capabilities, other methods can be used both at home and abroad.

In June, nearly 500 Marines, or about half a battalion, conducted the largest air assault exercise at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in a decade. And that’s just the start: 2nd Marine Division plans to double that to a full battalion air assault in the coming years.

It’s another type of training and capability that was common during the Cold War but may be a once in a career event for current Marines.

To provide the practice needed to send a MEF to war, Hedelund said Marines will rely on a combination of live, virtual and constructed training.

As Cabaniss described, even at a battalion-level exercise in Twentynine Palms, California, or elsewhere the headquarters staff in the command tent don’t know who’s out there on the battlefield and the trainers can simulate almost any size of force needed.

And for actual deployments, II MEF is seeing its Marines in the Baltic, working in Romania, Norway and having more of a focus in the Mediterranean Sea in the near future.

“We’re back in the (Mediterranean),” Hedelund said. “Spending time there, not just using it as a waterway to get to the Middle East.”

And all of those avenues have a larger purpose, the three-star said.

“We should know what bugs our adversary the most and give him a tough time and be in his backyard as much as we can.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.