Over the past nearly 20 years of fighting in low-intensity conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. troops have been afforded some of the comforts of home at larger military installations.

Major airbases in Afghanistan like Bagram and Kandahar or al Asad in Iraq once housed fast food and coffee joints like Burger King and Green Beans Coffee. Some had sprawling recreational facilities that featured video games, TV and access to the internet.

It’s long been a joke among Marines who served in these combat theaters that experiences of the war varied depending on one’s location.

At the height of the Corps’ participation in Afghanistan, dozens of small outposts dotted the rural Afghanistan landscape of Helmand province, where Marines lived in austere conditions and at times relied on air resupply as the safest and most efficient way to sustain their combat power.

Rotations in and out of these outposts to larger bases, like the sprawling Camp Leatherneck base in Helmand, afforded a short moment to rest and refit, or provided access to a store to buy snacks and tobacco products, and send emails to loved ones.

But as the Corps plans for a future war with rising near-peer rivals like China in the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, the Corps will have to retrain a force and retool a culture accustomed to easy access to large quantities of supplies from everything to weapons, vehicles and food. These supplies often are referred to as the iron mountain.

That also means the days of Green Beans Coffee and Burger King on your next combat deployment will likely be a thing of the past.

Marines are no strangers to living and fighting in austere conditions, an annoying mantra from Marines in the field is, “if it’s not raining, it’s not training.” That experience has tortured Marines for generations and was hilariously captured in the well-known Marine humor comic strip known as “Terminal Lance.”

While Marines will likely adapt to the lack of home comforts with little trouble, the Corps itself has operated over the past 20 years under the assumption that its forces will control the air space, allowing the Corps to operate supply chains with relative ease.

And because American military power dominated the skies, fears of enemy surveillance or enemy drone aircraft spotting U.S. military outposts was not a general norm of daily operational planning or consideration.

The network of American eateries, internet cafes and mountains of American military hardware spread across America’s counterinsurgency conflicts flaunted America’s hubris and its ability to dominate the battle space.

With no force in the region capable of posing a challenge, America was able to sustain and move massive amounts of military hardware and comforts of home to troops operating in the region.

Internet and phone cafes blasting a massive easily detectable electromagnetic spectrum signature were the norms of the time.

Now with sophisticated drones, aircraft and enemy sensors above, the Corps and the military will need to reconsider its past operational experience and ensure its forces are harder to pinpoint.

Some of these lessons are already being borne out of operations in Syria, where Marines and pilots are learning to contend with adversarial nation-state technology, drones and electronic warfare.

Your next combat deployment

In the next big fight, the Corps will be distributed among small island bases or floating barges, survival in this fight will require Marines maintaining a minimal observable footprint to enemy Chinese drones and aircraft spying from above.

That means Marine commanders will need to learn to operate and sustain their force without a glut of supplies.

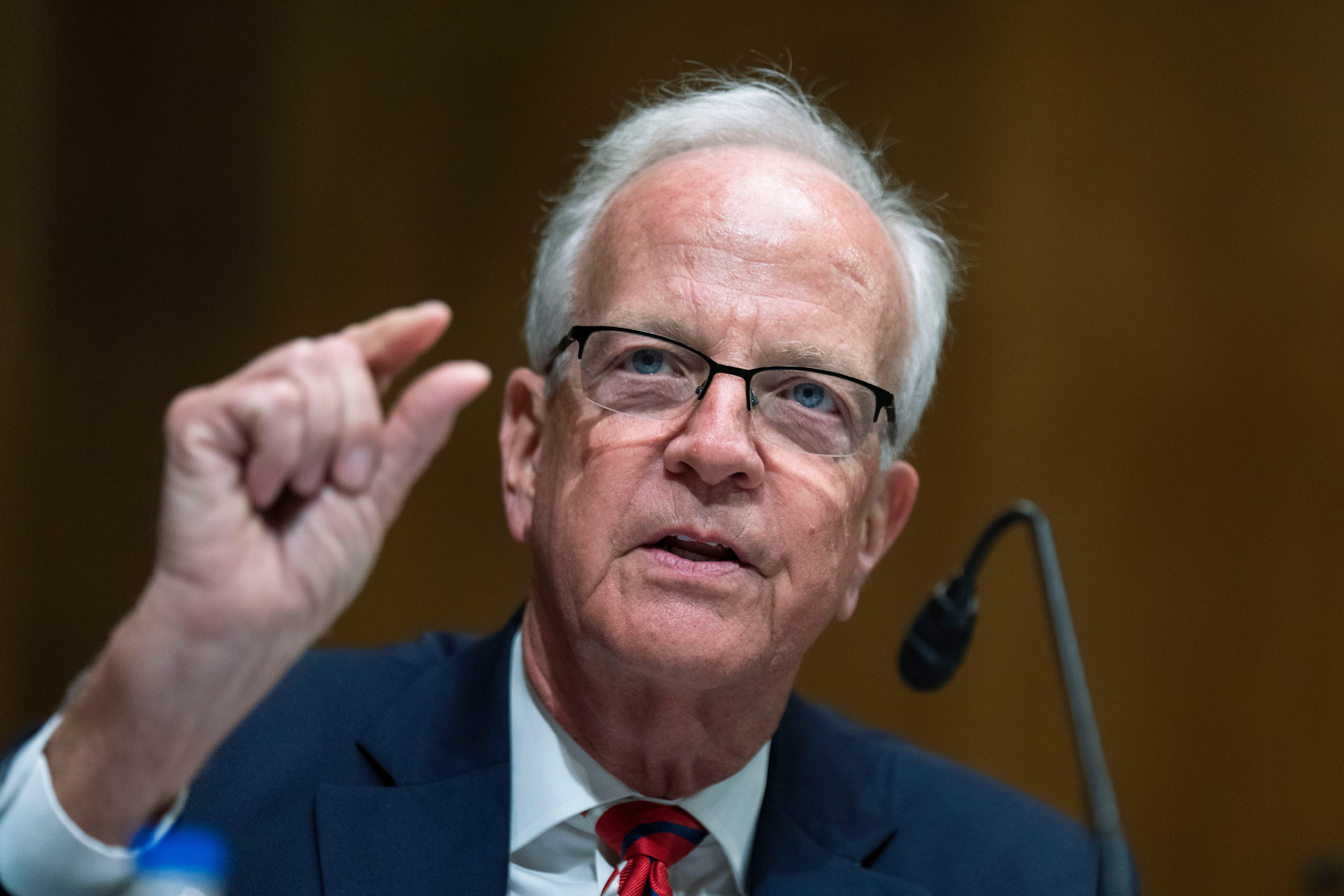

“We can no longer sustain and maintain the iron mountain” Marine Brig. Gen. David Maxwell, assistant deputy commandant for installations and logistics, told Marine Corps Times in an interview. “We have to minimize the amount we bring to shore.”

It’s just one of a slew of challenges the Corps now faces as it tries to solve the conundrum of how to supply and protect its force spread across many miles and small outposts.

And the Corps is taking serious stock in addressing its logistic challenges and is looking forcewide for answers.

This quarter, the Corps is looking to every Marine to help solve its sustainment and logistics problems focused on three main lines of effort: global logistics awareness, diversifying distribution and improving sustainment.

It’s part of an innovation challenge supported by the commandant and the Marine Warfighting Laboratory that has been going on for several years now.

“Most of the problems the Marine Corps have already been solved in the barracks,” Maxwell said.

RELATED

But, for the past 20 years the Corps has been a “wheeled distribution force” he said.

“The last time I checked, the ability to us an MTVR [medium tactical vehicle replacement] or a Humvee, or a JLTV [joint light tactical vehicle], in a maritime domain to distribute from afloat to an operating base ashore has not proven very successful,” Maxwell joked.

To sustain the force in a highly contested environment will require the Corps to look at everything from cyber, drones, artificial intelligence and crunching large quantities of data.

The Corps will need an awareness of its gear and condition, consumption rates, and size and location of its forces.

“Being able to see that picture and being able to anticipate in a manner to be able to sustain and supply what may be distributed forces over long or longer distances” will be vital for the Corps, Maxwell explained.

That will require the Corps to be able to analyze large quantities of data while also rely on artificial intelligence to predict when parts may need to be shipped to a location because something on an aircraft or vehicle is expected to break.

But that also comes with its own challenges, as the cyber domain is “increasingly contested,” Maxwell said.

Rival tech-adept forces could target the Corps’ logistics and artificial intelligence systems to glean important information or even to sabotage supply chains.

Vital parts for the high-tech F-35 stealth aircraft sent to the wrong location could impact the readiness of an entire squadron, putting Marines at risk.

Precision in quantity, time and space will be key for the Corps operating in this environment, Maxwell explained.

The Corps may also have to expand the training of various primary occupations. A Marine trained to drive trucks with motor transport may also have to learn to fly drones to ensure supplies are delivered the “last tactical mile,” Maxwell said. “It’s not something we’ve done.”

Drones and automation will feature heavily on the Corps’ plans to sustain its force in the Pacific.

A drone takes a driver out of a vehicle, improves safety, keeps Marines out of harm’s way, and also lightens supply loads because the cargo doesn’t require as much armor protection without a human passenger, Maxwell said.

The deadline for Marines to make a submission to help the Corps solve some of its future logistics problems has been extended until Feb. 25.

Marines can visit the MARADMIN online for more details.

Shawn Snow is the senior reporter for Marine Corps Times and a Marine Corps veteran.