“The Marine Corps will either make you, break you or kill you,” Manny Vega had told his son, Patrick.

That conversation now haunts the former Marine scout sniper.

Patrick Vega appeared to be a healthy 21-year-old when he shipped off for recruit training.

He enjoyed hiking and swimming, and had worked as a lifeguard. His mother and father, Amy and Manny, both described him as very fit, easy going and well-liked.

RELATED

But Patrick Vega’s sudden death from cardiac arrest while at the San Diego, California, recruit depot triggered an investigation and now a whirlwind of changes across recruit training.

During his roughly 11 days at the recruit depot, Vega’s health had slowly deteriorated under the eyes of everyone.

On his final night aboard the Marine recruit depot, March 23, 2018, wandering recruits on guard duty described the young recruit as being delirious, talking in his sleep, feeling cold and vomiting, according to details laid out in a command investigation obtained by Marine Corps Times via a Freedom of Information Act request.

Just before midnight, Vega’s pulse stopped.

Recruits on watch later detailed to investigators that his chest was no longer rising.

A drill instructor on duty that night was alerted immediately and performed CPR until first responders arrived on scene in mere minutes.

Vega was rushed to Naval Medical Center San Diego where he remained on life support for nearly 35 hours.

Medical practitioners listed the cause of death as cardiac arrest, but no other details or potential underlying medical issues were found in the course of the investigation.

An autopsy was not performed, due to his parents’ request. His father cited his knowledge of autopsy procedures from a lifelong career as a policeman as the reason against it.

“I know what killed my son,” Manny Vega told Marine Corps Times in an exclusive interview.

“The Marine Corps failed my son, and failed me completely,” he said. “The Marine Corps dropped the f*cking ball, negligence, ignorance, and just the gung-ho spirit that killed my son.”

Vega’s sudden boot camp death remains a medical mystery.

But details in the command investigation underscore a young man who struggled immensely to meet basic Marine Corps fitness standards just to ship to the recruit depot.

Following his dream

It was Patrick Vega’s dream to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Manny Vega had been a former Marine scout sniper who had earned the Corps’ highest award for noncombat bravery, the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, for trying to rescue people trapped in the deadly 1989 South Korea CH-53 crash that claimed the lives of 22 Marines.

The 21-year-old son, a native of Oxnard, California, had been recruited out the Ventura recruiting substation.

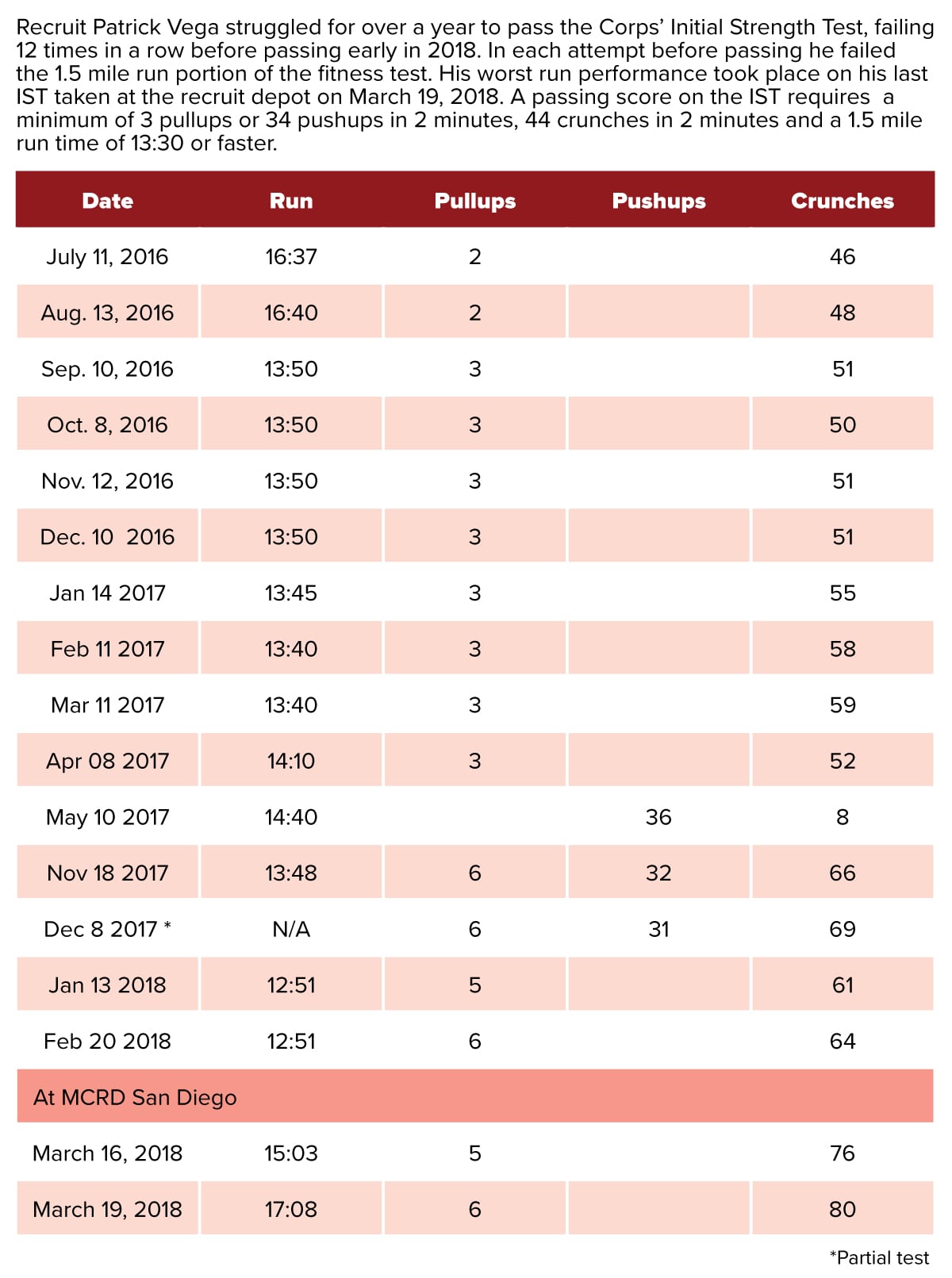

But he struggled for over a year to pass the Corps’ initial strength test, or IST — a fitness test required before potential recruits can ship to boot camp.

Vega failed the test at least 12 times, always on the run portion.

From July 2016 until May 2017, Vega failed the IST 11 times and eventually was booted from the Delayed Entry Program, or DEP, in June 2017.

He rejoined the DEP that October and failed the IST again in November.

Vega finally passed in both January and February 2018, with a passing run time of 12 minutes 51 seconds — just faster than the 13 minutes and 30 seconds maximum.

The test is a modified form of the physical fitness test required of Marines annually. Marine recruits also have to do pullups or pushups and crunches on the IST.

Vega’s final passing score on the IST finally heralded his entry into recruit training in March 2018.

But, Vega’s father say he’s skeptical about his son’s sudden passing score.

He told Marine Corps Times that he asked the recruiting station if the scores were fudged in order to ship his son to boot camp.

“He was a number to make mission,” Manny Vega said.

The recruiters have a responsibility to ensure they send qualified and capable people to the Corps, he added. Manny Vega himself did a short stint as a Marine recruiter before leaving the Corps in 1992.

It is not uncommon for future Marine recruits to struggle on the physical requirements to attend boot camp. For many, the IST is the hardest obstacle to overcome, as unlike other discrepancies that can be addressed with a waiver, potential recruits need to muster their own motivation to improve their fitness.

Many recruits have been known not show significant fitness progress until their ship date inches closer.

Marine Corps Times has learned that the Ventura recruiting substation is confident that it is executing its IST properly.

Moreover, a Marine assigned to the Ventura recruiting station described Vega’s fitness struggles to investigators.

Patrick Vega “demonstrated that he truly wanted to be a Marine,” reads a statement from the Marine at the recruiting station and included in the investigation.

“Vega’s involvement with our PT [physical training] and pool functions was sporadic. When he ran an IST he did fine with the crunches and pullups, but struggled with his run,” the statement said. “He knew that he was not within the physical standards to go to boot camp and was not making much of an effort to get himself ready or allow us to train with him or teach him different techniques to improve his performance on the run.”

The recruiting station noted Vega turned things around and emphasized his fitness the closer he got to his boot camp ship date.

But the question as to why a seemingly healthy and active young man struggled so hard to run a mile and half.

His mother and father both say that running just wasn’t Patrick’s thing, but that he trained and tried to prepare himself.

Manny Vega also said he didn’t want to get into his son’s adult business and micromanage his life.

A Military Entrance Processing Station, or MEPS, in Los Angeles cleared Vega as fit for duty for service in the military, finding no serious medical conditions.

The MEPS medical exam noted that Vega suffered from only 10 percent scoliosis of the lumbar spine, bronchitis from months earlier, surgery for a hernia when he was seven, pectus carinatum or pigeon chest, and the inability to do the duck walk.

The duck walk during the medical exam tests future military recruits for various mobility issues or knee injuries.

Still, the MEPS station ultimately cleared Vega as fit. The medical processing team at the recruit depot also found no serious medical ailments that could preclude Vega from military service.

An official at Marine Corps Recruiting Command told Marine Corps Times that Vega did not have a medical waiver to enlist in the Corps.

Vega stepped on the famous yellow footsteps at the San Diego recruit depot on March 12, 2018. That moment forward, his life and his health drastically deteriorated.

Failing runs

On March 16, 2018, the young recruit failed the IST while assigned to a boot camp receiving company. He scored a run time of 15 minutes, 3 seconds — more than two minutes slower than the score he achieved just a month prior.

Because of his poor performance on the IST, Vega was dropped to a physical conditioning platoon, or PCP, a purgatory for recruits at boot camp suffering from medical ailments or those unable to pass various physical standards.

PCP affords recruits time to condition themselves to be successful in training, but it also halts forward progress at boot camp until the Corps’ standards can be met.

On March 19, 2018, Vega failed the IST again while assigned to PCP.

He ran 1.5 miles in 17 minutes and 8 seconds — running two minutes slower than his test less than one week prior.

It was his worst ever showing on the IST.

On March 20, 2018, Vega showed his first signs of medical distress.

Drill instructors at a chow hall witnessed Vega vomit onto his food tray. From March 20-24 Vega would be seen vomiting eight to 10 times by various drill instructors and recruits.

As Vega showed signs of a potential illness, drill instructors routinely followed up with the young recruit, according to the command investigation, always affording him the opportunity to seek medical attention.

On March 21, Vega checked into sick call where a physician ultimately diagnosed him with an upper respiratory infection. He was prescribed Mucinex, Tylenol, lozenges for a sore throat, and Zofran for vomiting. He was also told to hydrate more.

Vega was given the option to go on light duty or to return to full duty. He chose full duty, citing his desire to get out of PCP.

On March 23, Vega attended an exercise training session with his PCP unit, which consisted of a few laps around a track. Vega was only able to complete a lap, which alerted officials supervising fitness training.

The young recruit complained that his throat was dry and that he felt like he was going to pass out. A corpsman on scene told Vega to sit out the rest of the physical training.

Throughout the rest of the day, Vega appeared tired, woozy and had trouble standing on his own at evening chow, witnesses said.

Vega was asked if he wanted to go to the hospital or sick call in the morning. He said he was not feeling sick enough to go to the hospital.

Company and platoon staff were told to keep an eye on Vega’s condition.

Around 7 p.m. that night, recruits on roving guard duty or fire watch were informed to keep watch of Vega and inform the drill instructor immediately if anything seemed strange.

That night would be Vega’s last at the recruit depot.

The recruits on fire watch detailed to investigators and in duty log books Vega’s delirious state and worsening condition throughout the evening.

Recruits said Vega would mumble in his sleep and sometimes would shout “recruit Vega, recruit Vega.”

He even attempted to get dressed in a hurry, appeared confused and complained of being cold.

For anyone who has ever gone through the stress of Marine Corps recruit training, talking in one’s sleep or sleep walking is a fairly common sight in a boot camp squad bay. It may not have been seen as necessarily out of the norm.

But Vega’s father told Marine Corps Times that he spoke with the recruits on guard duty that night, and they told him they were well aware of Vega’s poor health.

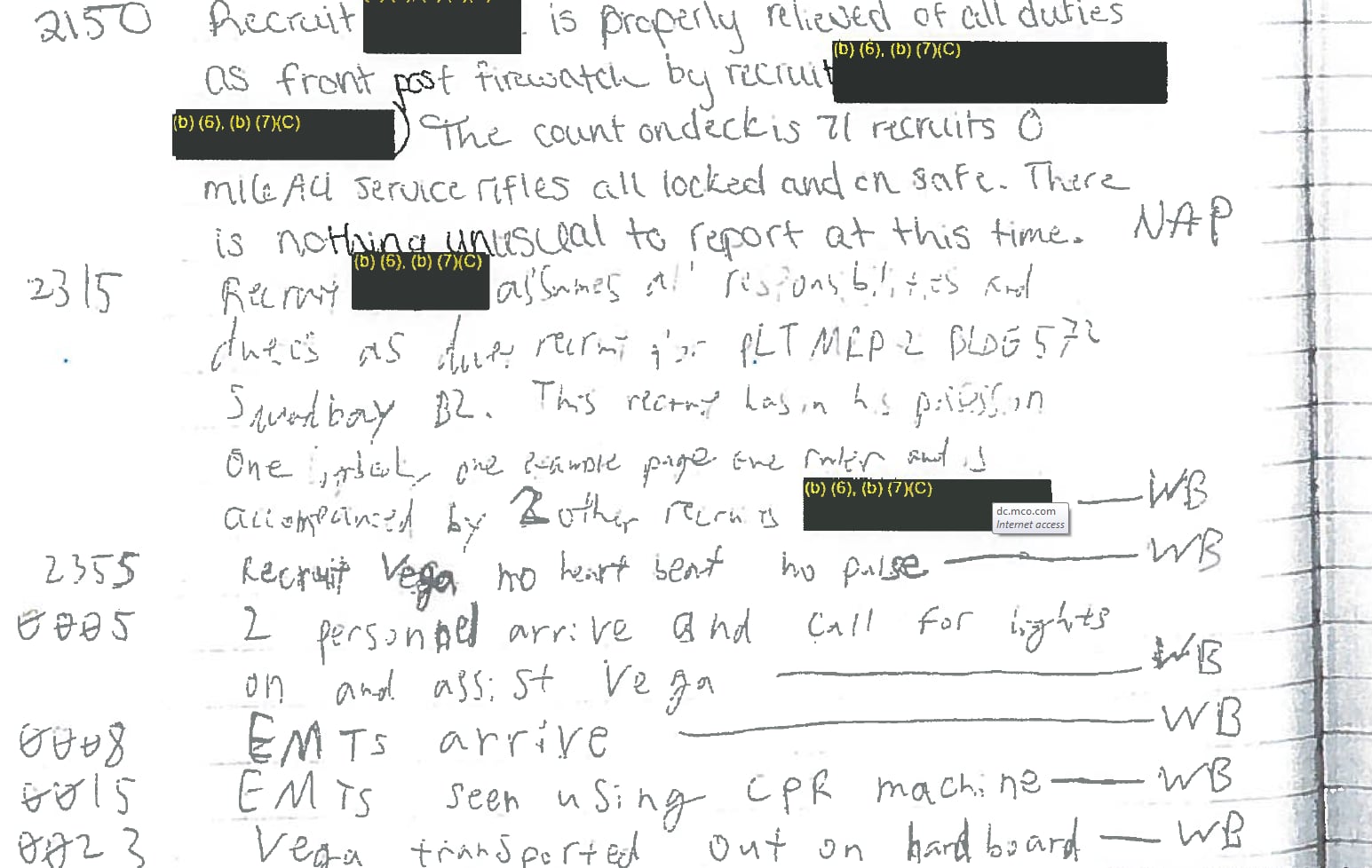

Around 11:53 p.m. on March 23, a recruit noted Vega’s chest wasn’t rising and that he had no pulse.

At 11:55 p.m., a drill instructor was informed and CPR was commenced.

Just after midnight, Fed Fire emergency services received the call and arrived on scene by 12:07 a.m.

Vega was transported to a San Diego hospital where he was placed on life support for nearly 35 hours.

He was declared deceased from cardiac arrest.

Changes coming

The command investigation did not find fault with anyone with Vega’s death.

According to the investigation’s findings, no single drill instructor witnessed all of Vega’s ailments or moments of vomiting and could not be held responsible.

Staff and drill instructors were trained in CPR and acted appropriately, according to the investigation.

However, some blame was laid at the feet of a series commander.

The investigation said the series commander “was in the best position, and had the responsibility for, comprehensive knowledge of recruit Vega’s medical status.”

A series commander is a relatively low-ranking officer between the rank of lieutenant to captain.

The investigation further stated that it “would have been prudent” for the series commander to activate emergency medical services instead of waiting for sick call the next day.

The series commander was removed from their duties supervising recruits at the depot.

While the investigation really didn’t fault any single person, the recruit depots are about to undergo some serious changes to help mitigate the chance of a death like this ever occurring again.

The depots plan to increase the number of medical drills within the Special Training Company to boost effectiveness and responsiveness of medical treatment.

The investigation noted that at a minimum STC personnel should perform monthly drills and continue to provide annual certifications. It also noted that personnel who performed CPR on Vega did so admirably.

Automated external defibrillators will be placed in the squad bays and posters will be displayed in the squad bays identifying criteria for recruits to notify their drill instructor of a medical emergency. An AED on site in the squad bay could speed up reaction time of a suspected medical emergencies.

The medical clinics will also evaluate any recruiting who fails the run portion of the IST. The investigation noted that a medical screening for failures on other portions of the IST were not necessary unless a medical reason was suspected.

“We understand that supervision is the key to proper execution and safe conduct of training,” Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego told Marine Corps Times in an emailed statement. “We believe these actions have increased emphasis on already close communication and coordination with Federal Fire (first responder) assets on board the installation.

So what the hell happened to Vega?

Because an autopsy was not performed, any possible underlying medical issues never were found.

“In one of the most controlled environments that exist in the world … and you have a healthy young man die of dehydration, basically — how … is that possible,” Manny Vega said.

But the investigation provided some speculation.

Patrick Vega may have discontinued his use of the prescribed medication Zofran, which helps with nausea and vomiting.

His continued vomiting on the March 23, could have resulted in his cardiac arrest.

“This remains only speculation,” the investigation reads.

His thorough medical examinations found no evidence of pneumonia or a serious viral infection that could lead to myocarditis, or a swelling of the heart from a viral infection, the investigation explained.

“The possibility of an unknown preexisting medical condition also remains,” the report stated.

The MEPS station and medical staff aboard the recruit depot “detected no pre-existing abnormalities aside from his pectus carinatum and minor scoliosis, NBHC medical officer staff stated that not all cardio or pulmonary abnormalities are detected during military entrance screening,” the investigation reads.

The investigation further speculated that Vega’s constant vomiting could have triggered pulmonary aspiration and triggered his cardiac arrest.

“While the circumstances make it impossible for us to learn what caused Pvt Vega to suffer cardiac arrest, we must strive to learn from this event and do all we can to prevent such a tragedy from occurring in the future,” the investigation reads.

“To that end, this investigation will be the subject of a recurring professional military education class at the Recruit Training Regiment military education class at the Recruit Training Regiment designed to train company personnel to recognize and respond to after-hours medical emergencies,” the investigation added.

Shawn Snow is the senior reporter for Marine Corps Times and a Marine Corps veteran.