On a dark, snowy mountaintop in Afghanistan in 2002, combat controller Technical Sgt. John Chapman roused himself from unconsciousness. He was alone on the Takur Ghar mountaintop before dawn, bleeding from several gunshot wounds, and for almost an hour, ferociously fought the al Qaida fighters surrounding him on three sides.

A Chinook helicopter carrying Army Rangers approached, and a group of militants took aim at it with rocket-propelled grenade launchers.

What Chapman did next cost him his life — but the military believes his actions also saved the lives of the Rangers. Now, after 16 long years, Chapman’s heroism on Takur Ghar will be honored in a White House ceremony Wednesday when President Trump posthumously awards him the Medal of Honor.

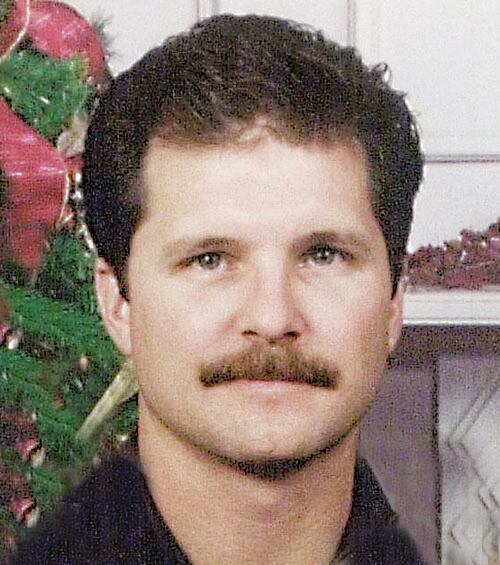

It represents the culmination of a long journey for Chapman’s family and friends, and the Air Force as a whole. Chapman, of Windsor Locks, Connecticut, who was 36 when he died, is the first airman to receive the nation’s highest award for valor for actions taken since the Vietnam War.

But figuring out what happened to Chapman on that 11,000-foot-high mountaintop in the early morning of March 4, 2002 — even confirming exactly when he died — has been difficult for the military. It’s led to some tough, painful questions about whether the Navy SEALs who fought alongside Chapman left him behind, mistakenly believing he was dead when they withdrew under heavy fire.

A key piece of evidence supporting the Air Force’s case that Chapman did not die within minutes of the SEAL team’s arrival on the mountaintop, but instead later regained consciousness and made a furious last stand by himself, was the grainy video feed from an MQ-1 Predator that flew overhead. This is the first time a Medal of Honor has been awarded based in large part on an analysis of video evidence.

In an Aug. 16 briefing at the Pentagon, a special tactics officer who worked on the 17-person team examining Chapman’s case walked reporters through the video and how the Air Force evaluated the evidence during an extensive 30-month review process.

Besides the Predator video, the evidence included testimony from his SEAL teammates and other troops, as well as ISR records and air crew testimony from an AC-130 known as Grim 32, which had “eyes on” for the entire engagement.

There were also observations from five members of an Army and Air Force reconnaissance team on the next mountaintop about four kilometers away, using high-powered optics and monitoring radio chatter from Chapman himself and enemy fighters, and mission logs. Also central was Chapman’s autopsy report, which showed he sustained bruising and cuts on his face, a broken nose and other injuries indicating he engaged in ferocious hand-to-hand combat.

The Battle of Takur Ghar was part of Operation Anaconda, a joint operation combining conventional forces and special operators that was one of the first major engagements of the Afghanistan War.

Chapman’s team, Mako 30, was one of several ordered to set up reconnaissance positions on mountaintops so as to provide overwatch and close-air support to conventional forces below. The team of SEALs helicoptered toward a mountaintop they thought was unoccupied, but it turned out to be “a hornet’s nest of enemy activity” and “basically their headquarters, or their strong point,” the special tactics officer said.

The al Qaida fighters unleashed a barrage of fire on their Chinook, code-named Razor 03, which was struck by multiple RPGs. One of the SEALs on his team, Petty Officer 1st Class Neil Roberts, was thrown from the back into the snow below before the helicopter crash-landed about five miles away.

The team — headed by Master Chief Special Warfare Operator Britt Slabinsky, the retired Navy SEAL who himself received the Medal of Honor for this battle — quickly decided that Roberts’ only chance of survival would be if they got another helicopter and returned to rescue him.

“They knew it had a significant chance to be a one-way mission, but they felt like that was the only chance Roberts would have to survive,” the special tactics officer said. Unfortunately and unbeknownst to them, Roberts had already been killed about an hour before they returned.

As the team expected, the heavily armed al Qaida fighters were prepared when they returned and once again met them with withering fire. But this time, they were able to get on the mountaintop. It was before dawn. They trudged through thigh-deep snow, wearing night vision goggles, in the “bottom of a fishbowl, surrounded on three sides by enemy with overwatching positions that are shooting down with machine guns, RPGs, heavy fire.”

Chapman led the charge without hesitation.

“He runs essentially straight up a steep mountain into the direction of enemy fire,” the special tactics officer said.

Video excerpts from the Takur Ghar battle, which the Pentagon posted earlier this month on its public DVIDS website, show the SEALs and Chapman emerging from their Chinook, Razor 04, at 4:27 a.m. A green circle superimposed on a blurry, pixelated figure shows how Chapman pressed on toward two chest-deep pillbox-like bunkers housing several al Qaida fighters.

Chapman burst into the first bunker, killed the two enemies there in close-quarters combat and seized it. He could have stayed safe within its hardened walls, which provided plenty of cover. But instead he emerged to assault the machine gun nest in the second nearby bunker, suppressing its fire and allowing his SEAL teammates to move forward.

That’s when Chapman was first wounded. The SEALs later described seeing him go down and the laser sight from his rifle, which was laying across his prone body, moving up and down with his labored breathing. Before long, they saw the laser stop moving and believed he had died.

Under heavy fire, the SEALs moved back to a ridgeline and continued firing until they were pushed down the mountaintop, the special tactics officer said.

Chapman’s three actions up to that point — his voluntary decision to return with the rest of the SEALs to try to rescue Roberts, his charge into withering fire and seizure of the bunker, and his risky emergence from the first bunker’s cover to assault the second bunker — were, alone, enough to merit the posthumous award in early 2003 of the Air Force Cross, the second-highest award for valor an airman can receive. Written testimony from four of his teammates was key to his initial award.

Even with a limited amount of available information on the still-highly classified mission, several members of the decorations board that reviewed Chapman’s case in July 2002 were stunned by his heroism and questioned why he was not up for the Medal of Honor.

“If this doesn’t rate a MoH, what does?” one board member wrote.

But Chapman’s story didn’t end there — he did much more.

Back in the fight

Chapman was not dead, but instead unconscious and temporarily incapacitated. He awoke after a few minutes, and continued fighting the enemy in the second bunker about 10 meters away for the next hour, the special tactics officer said. There was also another group of al Qaida on top of a ridge, heavily armed with RPGs.

A third Chinook, Razor 01, carrying a quick reaction force of Rangers and special tactics airmen approached shortly after 5:40 a.m. The al Qaida fighters on the ridge start to take aim with their RPGs at Razor 01. The sun had risen.

It’s impossible to know what was going through Chapman’s head at that point, but the special tactics officer believes he realized the Rangers would have a better chance of survival if he could suppress that RPG fire.

Chapman once again ran out from the safety of his bunker, into broad daylight. He placed himself in-between the bunker — with his back to the machine gun within — and the fighters on the ridge, and began firing.

“When he stood up and got out of the bunker, I don’t think he imagined he was going to survive,” the special tactics officer said.

Razor 01 got hit by an RPG when it was about 50 feet off the ground, the special tactics officer said, but was still able to control its landing.

But it could have been much worse for Razor 1. The special tactics officer said that when Chapman opened fire on the al Qaida fighters on the ridge, he forced them to put their heads down and suppressed their RPG fire as the Chinook approached.

“It’s easy to imagine that it would be a high potential for there to be a catastrophic loss of the helicopter had he not been engaging the enemy as the helicopter was on its approach,” the special tactics officer said.

It’s hard to tell exactly what happened to Chapman at that point, the special tactics officer said, but the large-caliber machine gun bullets — probably from a PKM — that ultimately killed him were likely fired shortly thereafter.

The Rangers poured out of Razor 01 — two were killed as soon as they emerged — and then fought for seven more hours to get to where Chapman fell. The entire battle took 17 hours from the moment when Roberts was thrown from Razor 03.

Years of questions — and finally, answers

For years after the Battle of Roberts Ridge, many in the Air Force felt Chapman deserved the nation’s highest award for valor. The 30-month review process of Chapman’s case began in March 2015, about a year after the services were ordered to review its cases of heroism to see if any merited upgrades to higher awards.

Lt. Gen. Bradley Heithold, the former commander of Air Force Special Operations Command, told Air Force Times in 2015 that the Air Force planned to recommend an unidentified post-9/11 Air Force Cross recipient for the Medal of Honor, citing new information that had emerged.

The review process included experts from multiple agencies and services, including the Army, Navy, Air Force, Joint Special Operations Command and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which created a digital reconstruction of the battlefield to measure its elevations and relative distances.

In June 2016, former Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James concluded Chapman had lived to fight on and recommended his Air Force Cross be upgraded. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis ultimately approved Chapman’s Medal of Honor.

This was the first review focusing entirely on Chapman’s actions, the special tactics officer said. The previous reviews were for after-action reports, or to determine what went wrong in the Battle of Roberts Ridge. He stressed that they didn’t set out to decide whether he merited a Medal of Honor, but intended to come up with as full and complete an accounting of the last events of his life as possible.

But reconstructing the events of a dark, chaotic morning is challenging — especially one that happened more than 16 years ago. And when making the case for a Medal of Honor, there can’t be any holes in the story, he said.

That made it even more important for the team to combine fragments of information from a wide variety of sources to assemble the whole story. And the review team tried, whenever possible, to match up firsthand information, such as testimony from participants in the Takur Ghar battle, with a present-day analysis of the evidence for corroboration.

“Any single layer, any single source, doesn’t tell you the whole story,” he said. “John’s teammates can give a really rich accounting, with a lot of detail, firsthand, for those first 15 minutes they were with him. The ISR video, for certain portions, tells us a lot of what’s going on. We can get a lot of good information from his autopsy and the trajectory.”

The autopsy showed Chapman was shot nine times, from different angles and different weapons at different times. He sustained seven of those wounds before he died, the last two of which struck his aorta and killed him within seconds.

The autopsy also showed one of those final, fatal bullets entered his back right side and traveled at an upward angle, exiting his neck on the left side. That trajectory would not have been possible had he sustained the fatal wound earlier in the battle, when he was in the bunker and at a lower angle from the enemy, the special tactics officer said.

That’s an example of how multiple pieces of evidence were combined to sleuth out when Chapman could — or could not — have been killed.

Before sustaining his fatal wounds, Chapman was also shot in his heel, calf, back, chest, liver and thigh, as well as multiple abrasions on his face and a broken nose. The doctor who conducted his autopsy at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan found that he could have been knocked unconscious by one or more of those earlier injuries — perhaps he was hit in the face by a rifle butt that broke his nose, the special tactics officer said, or passed out after a gunshot wound — but he still would have been able to move around and fight once he woke up.

The team of analysts also had to figure out who precisely was fighting during the second engagement, before the Ranger team arrived. The five members of the reconnaissance team on the next mountaintop observed somebody fighting, though they couldn’t quite tell who it was.

There were only two possibilities, the special tactics officer said: If it wasn’t Chapman, it would have to be members of al Qaida who had become confused and fired on one another.

But the Pentagon doesn’t think that’s what happened. The two bunkers were about 10 meters apart, he said, and even in the heat and chaos of battle, at that distance it’s hard to confuse the sound of Russian-made rifles with American rifles for about an hour.

The recon team also heard the enemy talking excitedly about an American on the mountaintop, and planning their assault.

Another special tactics airman who was monitoring a coordination frequency heard Chapman repeatedly transmitting his call sign, “Mako three-zero Charlie.” Charlie stood for combat controller.

The AC-130 crew’s observations provided more evidence Chapman continued to fight. They saw someone inside the first bunker had an activated infrared strobe, a weapon with a laser sight, and infrared glint tape. The militants had none of that, but all three were recovered with Chapman’s body.

Chapman also began the battle with 210 rounds of ammunition. By the time he died, he had fired all but one or two rounds.

The process was also controversial. In May, Newsweek reported that the question over when Chapman died, and whether the SEALs left him behind alive, had led to a clash between the Navy and Air Force, and was holding up approval of Chapman’s Medal of Honor.

The special tactics officer said the SEALs were no closer than 15 to 18 feet away from Chapman’s position when they believed he had died. But he also noted that the SEALs were operating under exceptionally difficult circumstances, and the fact that they originally went back for Roberts showed their intention was to not leave anyone behind.

Slabinsky also, in the heat of battle while trying to call in close air support, radioed in a report that Chapman had possibly been killed in action.

“It’s hard to overstate this — it’s a tactical decision under duress," the special tactics officer said. "As [the SEALs] were moving, they were under fire from three directions. [Slabinski is] dragging a guy whose foot would later be amputated. He himself had got shot through the leg, through his boot. ... They were in thigh-deep snow, it was in the middle of the night. They’re on [night-vision goggles]. ... It gives you an idea of the chaos and confusion.”

The special tactics officer said that several factors hindered the effort to account for what really happened to Chapman in the first years after his death. The mission was classified, which resulted in “stovepipes” and restricted access to certain records like his autopsy when the decorations board met.

What’s more, the battle was a “traumatic event” for the special operations community and the military as a whole, he said. Seven troops were killed in the Battle of Takur Ghar, and at the time, the military was focused on fixing what went wrong there — not on properly recognizing the heroism of troops who fought there.

“Even in the moment, no one had a full picture of what was going on,” the special tactics officer said. “It’s only now, as we zoom out and are able to integrate all these things, where we stitch all these things together.”

But one thing on the video is indisputable, said the special tactics officer: The bravery of Chapman and the SEALs and Rangers he fought alongside.

“If you watch the [video], heroism jumps off the page at you,” the special tactics officer said. “You don’t have to do 30 months of analysis to see that. It chokes you up, and makes you see how incredible the sacrifice is.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.