Since the Biden administration urged federal agencies to name designated leaders to spearhead diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, the creation of chief diversity officers is facing pushback from conservatives and some DEI practitioners who question whether that’s even the right way to address barriers.

Recent resignations at the State Department and the Pentagon have thrust these officials and the work they do into the spotlight, drawing attention not just to the fact that vacancies leave a leadership gap, but to concerns about whether a chief diversity officer even has the resources to do the job.

A spokesperson for the State Department said it will be appointing a new chief diversity and inclusion officer to replace Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, and is in the process of reviewing candidates “for that important position.” The Department of Defense has not said whether it’s planning to replace Gilbert Cisneros’ role as chief of the diversity and inclusion office. Cisneros is stepping down in September. A spokesperson declined to comment further.

“I do think that a lot, or some, of this is well-intentioned,” said Mike Gonzalez, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation. “It’s people who actually do care a lot about disparities. They care a lot about equality. They do think that racial crimes have been committed in our history, which they have. That’s undeniable. But DEI also reinforces the message to people that are considered ‘victim categories.’ [It] confines them to that. Ultimately, DEI does not fix the problem.”

Where did CDOs come from?

Though DEIA feels like a modern idea, scholars point out that the position of chief diversity officer, at least informally, has roots in the integration movement of U.S. universities in the 1970s.

Some also worked as compliance or affirmative action officers following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but the idea of chief diversity officer as a built-in function of corporate or government leadership has gotten more attention in recent years.

President Donald Trump acknowledged in a 2020 executive order that “training employees to create an inclusive workplace is appropriate and beneficial,” however he cautioned against that which is “blame-focused.”

“Such ideas may be fashionable in the academy, but they have no place in programs and activities supported by federal taxpayer dollars,” he said.

Then, in one of his earlier moves as president, Joe Biden, who also promised “the most diverse cabinet representative of all folks,” directed agencies to consider installing a chief diversity officer as a way to bring leadership to related goals to hire, retain and promote fairly all groups of employees.

What the data does, and does not, show

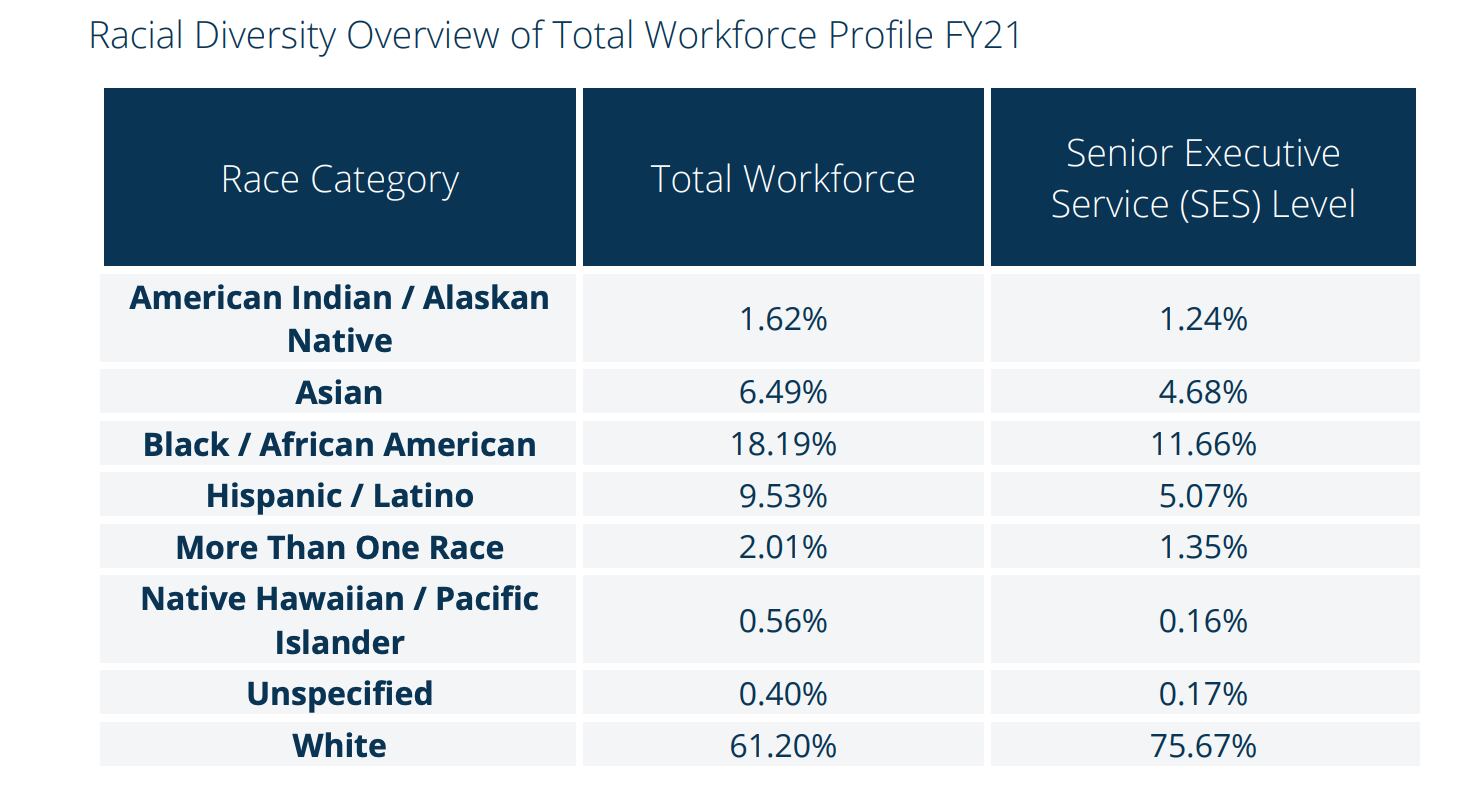

The federal workforce today identifies as roughly 60% white, compared with 75% of the country as a whole, and 55% male. About 30% are veterans and 17% have a disability, according to the latest governmentwide figures from the Office of Personnel Management.

About a third are veterans, and 6% is a member of the LGBTQ community.

While the general workforce mirrors racial breakdowns of the U.S. population, critics say that pockets of the federal workforce have greater gaps, like the Senior Executive Service, tranches of Pentagon leadership, the national security workforce (particularly for neurodiverse applicants), and the Foreign Service.

“Even with decades of progress building a federal workforce that draws from the full diversity of the Nation, many underserved communities remain underrepresented in the federal workforce, especially in positions of leadership,” an OPM spokesperson said in a statement.

For one, the percentage of persons with disabilities in the intelligence community decreased in 2021 for the first time since 2016. The National Security Council did not respond to several requests for comment about its diversity initiatives.

Critics of DEIA initiatives have also said they don’t believe the government’s proven there’s a problem, and without that, it’s difficult to buy into solutions, however well-meaning they may be.

“I don’t think the case has been made,” said Erec Smith, professor and co-founder of Free Black Thought, a nonprofit dedicated to highlighting viewpoint diversity and individualism within the Black community.

“I don’t think if African Americans have 30% of the population, they need to be 30% of every workforce,” he said. “I think when you start doing that, you won’t necessarily throw out merit, but you tend to because you’ve got to find those numbers. You’re not taking into consideration that maybe people don’t want to do that job. Maybe the people who want to do that job complement a certain socio-economic background or something like that.”

Gonzalez also pointed to the way disparities are measured and evaluated. Instead of lumping people into monolithic groups based often on one race, disaggregate that data to account for other factors, like nation of origin or household income, that might affect outcomes.

“[Then] you start getting some idea of a policy to help treat the disparities and not just say, which is what DEI philosophy says, [that] all disparities are prima facie evidence of systemic racism,” he said.

Getting to those answers requires a level of data granularity that the government is trying to reach. The Government Accountability Office has called out the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and OPM for incomplete data on pay disparities and disability rates.

“Data is the core of of any effective accountable DEI strategy or DEI process,” said Lily Zheng, author of “DEI Deconstructed: Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing it Right,” a guide for employers.

Zheng said they’ve seen some indication of government’s willingness to do that in its strategic plans and executive orders, but absent from them is a mechanical understanding of that actually works, which could mean there lacks a quantitative oversight mechanism.

“I don’t think anyone wants to be throwing money at DEI that doesn’t go anywhere, that doesn’t do anything,” Zheng said. “We shouldn’t be doing the work just for optics’ sake. We see DEI initiatives decoupled or functionally separate from this data piece, when in fact everything should be rooted in effectiveness, impact and data.”

The state of CDOs

A review by Federal Times found a range of implementation of CDOs, not all of which are easy to find on agencies’ websites, a point Mark Hanis of Inclusive America highlighted.

“Government needs to be much more transparent about who these people are, what their authority is, and what are they actually doing,” he said.

Many agencies, like the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Department of Agriculture, and Department of Commerce, all have designated CDOs, and the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Interior are in the process of hiring one. Agencies including the Department of Homeland Security and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission said they have an official who functions as the CDO and is embedded in human capital offices.

There are full-time or acting CDOs in place at 21 of 24 main agencies, Janice Underwood, OPM’s DEIA director, told Federal Times.

RELATED

Via a June 2021 executive order, agencies have been encouraged, but not required, to establish a formal CDO position, or one generally for a “diversity and inclusion officer.” The White House’s expectation is that this position is distinct from an equal employment opportunity officer.

“Not every chief diversity officer role is created equal,” said Kevin Johnson, director of DEIA at the Partnership for Public Service, a government watchdog.

He and others pointed out that it’s also not enough just to have the position; the CDO must be afforded access to resources and standalone authority to be able to effect change.

“Rarely do you see a person who has a C-suite title who doesn’t have a team of at least three or four people,” he said. “Many of these chief diversity officers have one, maybe two, full-time employees and the rest of time, they’re trying to borrow support.”

Hanis said it will be critical that agencies institutionalize well-supported CDOs that are equals at the head table of government instead of propped up acting officials whose momentum is subject to political erosion.

OPM, too, has acknowledged that “execution of agency-specific DEIA plans will require leadership and accountability at the highest levels of agencies” and long-term budgets and staffing.

“One of the biggest challenges we often face is time,” Underwood said. “The reality is that federal budget cycles, hiring and staffing all take time. Agencies created and released DEIA strategic plans and are working hard to put the structures and people in place to help our agencies become the diverse, equitable, inclusive, and accessible organizations we aspire to be.”

RELATED

Zheng considers themself a opponent to CDOs, citing new research from the London School of Business that found companies with senior diversity leaders don’t necessarily enjoy better DEI performance.

“Essentially, what this research is strongly suggesting is what practitioners have been worried about for a while, which is that the presence of a CDO actually may be giving permission to other senior executives to care less about DEI,” said Zheng.

It has to be everyone’s job in an organization, Zheng said, who critiqued the government’s DEIA plan for setting out sweeping goals that may not show how each person, no matter how junior, is a stakeholder.

The other red flag to watch out for is employee resource groups becoming “free volunteer” labor for agency heads to offload diversity issues, Zheng said.

A spokesperson for OPM also said in a statement that public servants at all levels of every agency must contribute to advancing DEIA in the federal government.

Political pressures

DEIA work has also received pushback from some in Congress who see this work as merely political or unfounded.

At a June hearing before the House oversight committee, Abercrombie-Winstanley, State’s first chief diversity and inclusion officer, defended her office against claims that it threatens merit system principles and lowers employment standards.

Rep. Matt Gaetz has led some Republican initiatives to eliminate diversity officers from the Pentagon, while others, like Republican Rep. Ralph Norman of South Carolina proposed an amendment to the 2024 defense budget that would gut these program offices altogether.

RELATED

To redirect priorities to what they claim to be more credible threats to America’s military and government, Rubio and Rep. Brian Mast (R-Fl.) proposed legislation to undo DEIA performance requirements for civil service evaluations and advancement criteria for senior positions at the State Department.

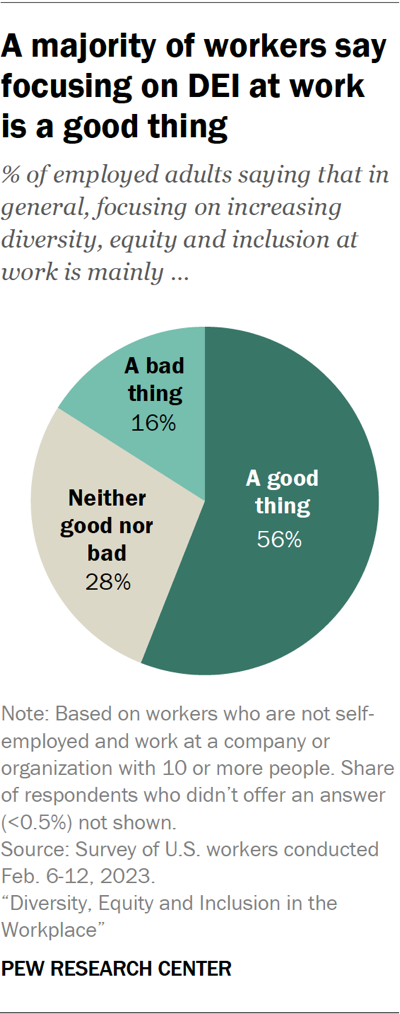

The American public, however, has a generally positive view of these principles at work, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

Against all those pressures, the government has looked to hire CDOs where there are none. So, who wants the job?

Johnson said interest often stems from current civil servants who know how the bureaucracy works and ask their colleagues at neighboring agencies whether their leadership is willing to support DEIA work and not just give it “lip service.”

In the private sector, there has been an dramatic increase in diversity and inclusion roles in the last five years. However, the overall proportion of companies with a CDO hasn’t grown as sharply in part because turnover for these positions is very high, according to data from LinkedIn and Russell Reynolds, a management consulting firm.

There isn’t yet enough data on federal CDOs, but Johnson and Hanis said they wouldn’t be surprised if similar trends affect them in the next few years.

OPM has said it will review whether or not a formal occupational series for CDOs would be appropriate, and that could help craft a specific metric to track employment.

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.