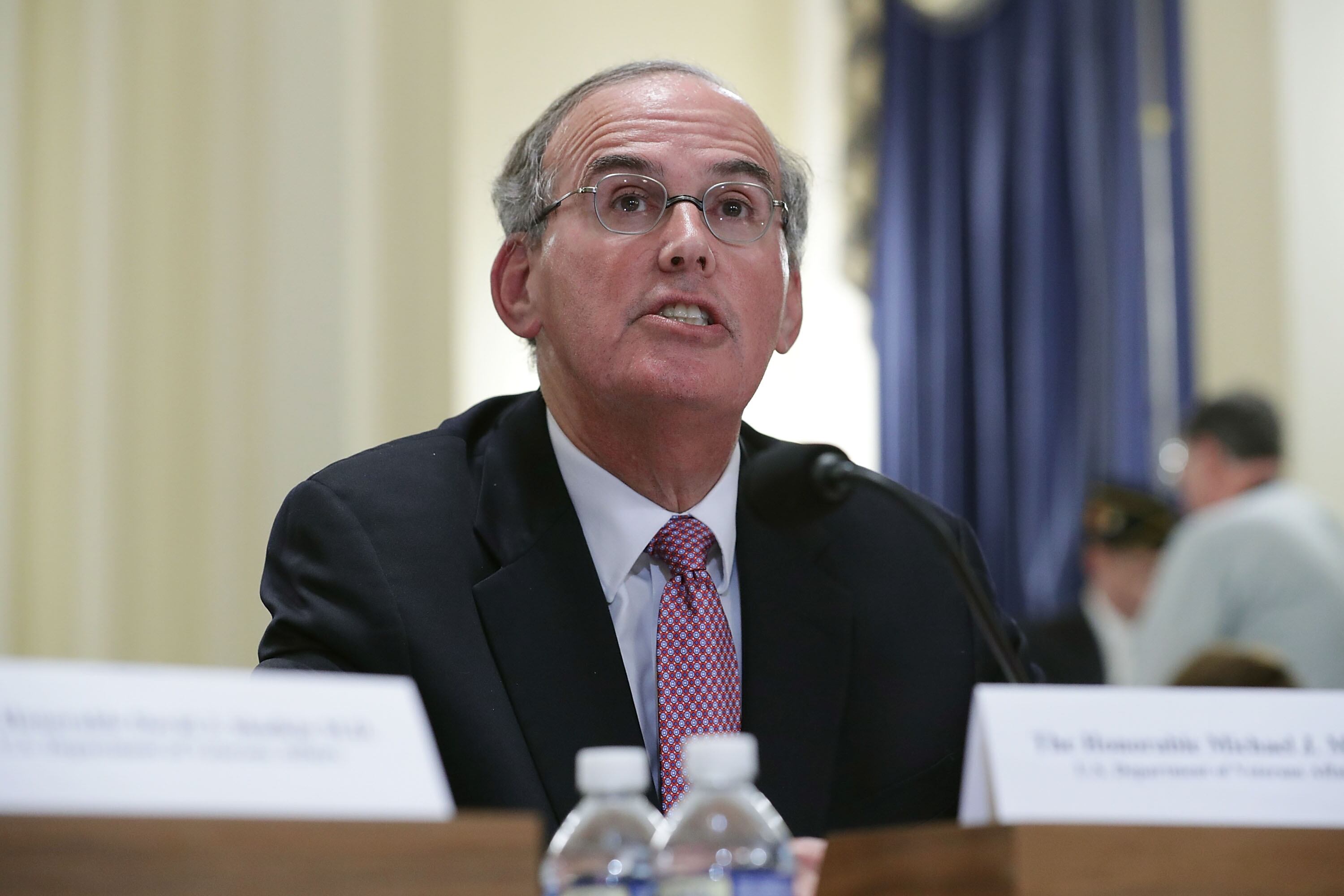

WASHINGTON ― House Armed Services Committee Chairman Adam Smith, D-Wash., recently led the Democrat-run House’s complicated negotiations on the sweeping defense policy bill for 2020 and will do so again for 2021.

The compromise National Defense Authorization Act authorized a new Space Force and $738 billion for the Pentagon. In part because it included parental leave for all federal workers, Smith called it "the most progressive defense bill we have passed in decades.”

With the Senate and presidency held by Republicans, Smith’s first cycle at the helm was marked by a tough fight with his counterpart, Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., but that’s not all. When House Republicans en masse opposed their chamber’s NDAA, Democrats added progressive policy measures to muster enough votes to pass the House. But those provisions were stripped out in talks with the GOP-controlled Senate, prompting criticism from the left and some advocacy groups.

It excluded a broad ban on “PFAS” chemicals, restrictions on the president’s ability to transfer military money to his southern border wall project, a cut to the W76-2 low-yield nuclear warhead and prohibitions on U.S. military support for the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen.

Gone also were provisions that would restrict the president’s ability to go to war with Iran without congressional approval, that would override President Donald Trump’s ban on transgender individuals joining the military, and that would reverse restrictions on the president’s authority to transfer prisoners from Guantanamo Bay to the U.S.

Smith, speaking with Defense News on Dec. 27, said he would like to revisit many of those issues in the 2021 bill.

Several progressive provisions from the House NDAA wound up on the cutting-room floor, border wall among them. What could be readdressed? What would you like to come back to?

I think we resolved a lot of things, and we’ll have less to offer next year because there’s better understanding of what’s possible. In terms of what’s within our jurisdiction, three things were not resolved the way I liked: the border wall being one of them, transgender being the second and Guantanamo Bay being the third.

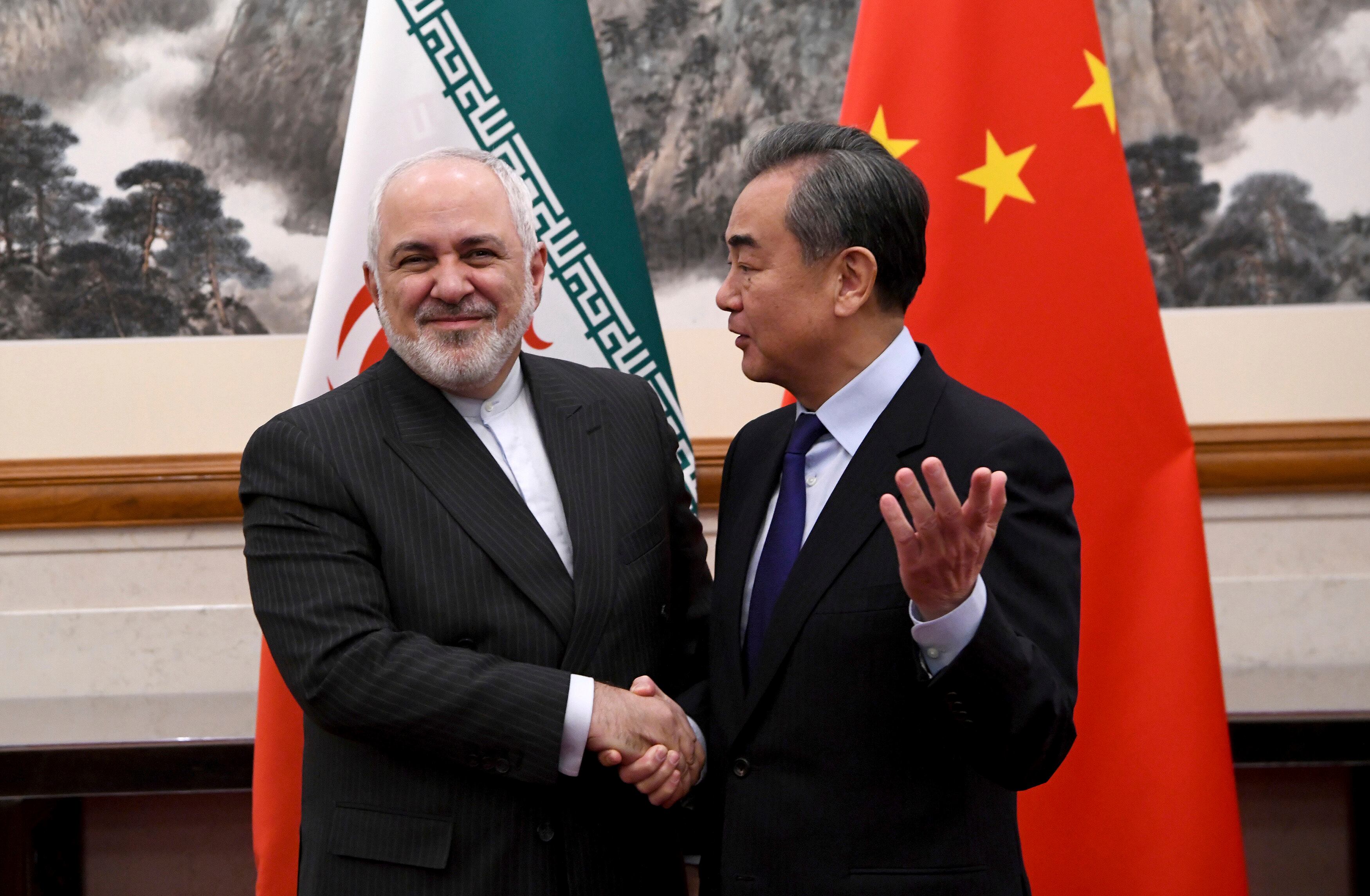

There were a couple others outside our jurisdiction that became very important to do with arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates around the Yemen conflict, restrictions on the president’s ability to commit troops without first coming to Congress ― the Iran provision the big one. None of that is in my jurisdiction, it’s all within the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

The fifth would be PFAS. Part of that is not my jurisdiction, and part of it is. The nuke provisions would be a sixth ― the limit on the low-yield nuclear weapon. I also still have strong feelings about the fact that we’re spending too much money on the nuclear enterprise: plutonium pit production, and concerns about what’s going on with the [competition for the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent] GBSD.

Gitmo, transgender, nukes, the border wall ― and Yemen, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Iran. I think all of those issues were not resolved to the satisfaction of me or the Democratic Party.

The question is what’s doable in those areas or what statement do we want to make on the policy. Even if we know Jim Inhofe and Donald Trump aren’t going to change their minds in just eight months, do we want to take another run at it, and if so, how?

You’ve expressed commitment to talk to outside groups about the NDAA. Do you plan to talk to candidates in the 2020 Democratic field or the eventual Democratic nominee, and could that affect what goes into this next bill?

I think that’s realistic. One of the things I hope to achieve is to offer up a clear Democratic national security policy. I have multiple responsibilities here, and certainly I take my bipartisan responsibility seriously, but given that we have a Republican president and Republican Senate, the clearest declaration of what a Democratic national security policy would look like will come from two places: my committee, and whoever our eventual nominee is. And yes, I think it would be worth it to have that conversation.

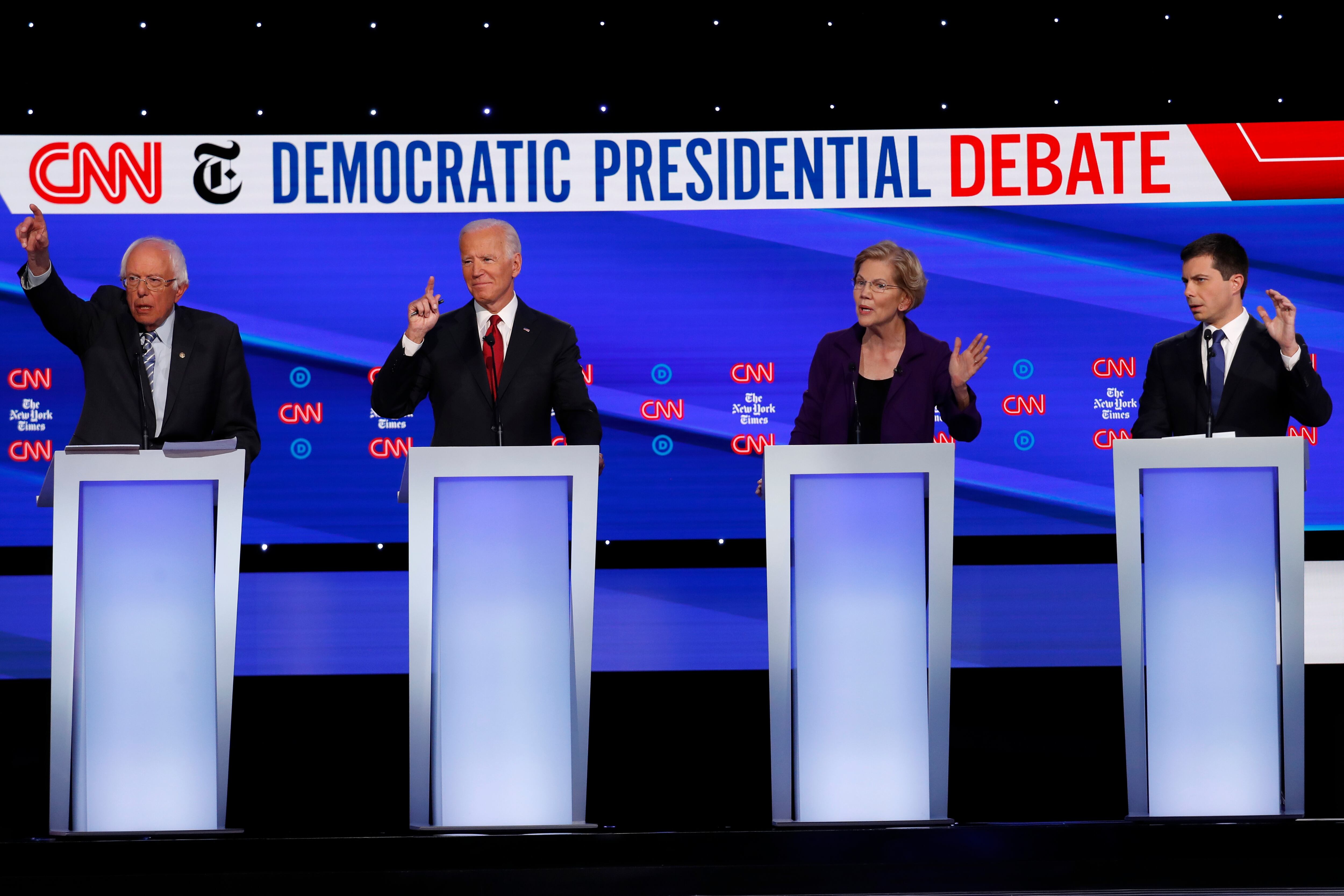

Among the Democratic field, the main question for Democrats is whether it’s a good strategy to go left or to opt for a more centrist candidate. What’s your point of view?

I kind of reject the way you phrased it. I don’t think it’s an artificial point on a line. The real debate within the Democratic Party, independent of who the specific candidate is, is do we need a revolution, or do we need what I like to call capable, pragmatic, center-left, progressive problem-solving. And I definitely fall in the latter camp.

I don’t think the victory lies along radical transformation. I think when the country looks at Donald Trump, mostly they are distressed by how erratic he is and how reprehensible what he says and does is. They are looking for calm, steady, thoughtful leadership. Now I also think that thoughtful leadership is center-left, not right. I think the U.S. wants an efficient, effective role for government ― a private sector that has at least some regulation so that corporations don’t completely run amok. A pragmatic problem-solving approach should be center-left, but I don’t support the notion we need to blow the whole thing up, and that’s a debate point between some of the top candidates.

Do you have a favorite candidate?

I don’t have a favorite candidate. I would say, in terms of that message that I just outlined, that essentially [Pete] Buttigeig and [Former Vice President Joe] Biden are articulating that message that I would support. [New Jersey Sen.] Cory Booker is articulating it, and to some degree [Minnesota Sen.] Amy Klobuchar. Those are the four candidates that are trying to build off of our success in 2018, and our success in 2018 led to the 14 freshmen on my committee. Every single one of those 14 freshmen falls into the capable, pragmatic, problem-solving bucket. That’s where we had success and that’s where I think we should build on with our nomination going forward. Will Democrats articulate a clear strong national security policy going forward? I think that’s very important.

Is there a foreign policy or national security issue that’s not being discussed or not being discussed enough that the field ought to be talking about more?

You’re out there trying to win an election, and frankly these issues are not at the top of people’s lists of concerns. They’re there, but they’re more concerned about infrastructure, jobs and wealth disparity. As you see from the debate, it’s never the first topic they talk about. I think it’s important to articulate that policy.

Both the president and candidates across the the Democratic field are talking about ending “forever wars” in the Middle East. The Washington Post’s report on Afghanistan put it back in the headlines. Should troops stay there any longer?

What is clear from the Bush experiment is that forcing regime change and government change at the barrel of a gun is an enormous mistake. It’s an enormous mistake to do it in Iraq and it’s an enormous mistake to do it in Afghanistan, and I think the public rightly looks at that and says it’s not the right thing to do. It’s not a realistic foreign policy to imagine dropping a bunch of troops down in a foreign country and reshaping it in our image. That’s not an appropriate role for the U.S. to play anymore.

What I am worried about is where we go from that: “Therefore we should not play any role in the world.” I reject that. I think that role needs to be more balanced between development, diplomacy and defense. I also reject the idea that the U.S. is a malign actor on the global stage, though certainly there are things that we have done wrong. I think it can be a force for good, and I do think we should focus on that.

We do have to protect our citizens and our country, and in some cases our Western allies, from transnational terrorist groups. That is a real threat.

At the same time, you have Afghanistan, Syria and Iran sucking up the oxygen. The defense secretary recently took a tour of Asia, talking about reorienting for competition with China. Is that the right objective? You’ve got transnational terrorism and great power competition. How do you make that choice, and how does a president articulate that?

Containing the transnational terrorist threat is a big part of what we’ve got to do. As we’ve seen in Afghanistan, ungoverned spaces lead to groups like al-Qaida and ISIS getting a safe haven and attacking us.

This isn’t primarily a military operation. How can you avoid the ungoverned spaces from being created in the first place? That’s development, that’s diplomacy, that’s partnerships with regional allies.

As far as Russia and China are concerned, we need to be clearer about what we need to stop and the reason we need to stop it. The world will be less stable and less prosperous if Russia and China are able to bully people with a kleptocratic, autocratic approach to economics, to governance. Russia and China, as they’re operating [around the globe], they are promoting a kleptocratic and autocratic approach as opposed to political and economic freedom.

That is contrary to global interests, and I think it is more likely to lead to conflict. Where I part ways with the neocons is the idea that we should force this upon people through military action. But I don’t think we should retreat from the world, so I don’t want to see us look at China and Russia and say: “We have to get into an arms race.” Looking at Russia and China, I happen to think that a big part of what we need to do to deter them is to build up alliances, so that it’s not just us deterring them, it’s us, our partners and allies around the globe who share our values and interests.

Is any Democratic candidate or the president doing a good job of articulating the national security challenge that comes with great power competition? Is anybody speaking publicly about China in the right way?

I think the president is doing a disastrous job of it. His general approach seems to be to support the autocrats at every turn ― rhetorically if nothing else. I mean, what he has said has been supportive of [Turkish President Recep Tayip] Erdogan, [Saudi Crown Prince] Mohammed bin Salman, [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and [North Korean leader] Kim Jong Un.

I think the president is distrustful of alliances. He tends to be more supportive of autocratic governments than democratic ones, and wants to withdraw the United States. I think his policy is just completely wrong.

The Democratic candidates have not been articulating them because their focus has been on domestic issues. I would say that probably Buttigieg best articulates it when he speaks about it. To some extent, Cory Booker as well. I confess at times it’s hard for me to follow what Joe Biden is saying, but I would think Joe Biden’s orientation is close to what I’m saying.

It seems like the services are increasingly realizing they’ll have to make budgetary trade-offs to focus more on Russia and China. With budget requests expected in a few months, is there outdated hardware that you expect to see less of, and how can a Democrat-led House exercise its leverage?

I can’t give you a clear, intelligent answer to that very complexly worded question. Part of the reason we put together the [HASC’s long-term defense strategy] task force with [Massachusetts Democratic Rep.] Seth Moulton and [Indiana Republican Rep. Jim] Banks, that’s what they’re supposed to do. What Russia’s been able to do was undermine us on the cheap from information warfare and cyber campaigns and social media and disruption. That’s an example of very cost-effective technologies that enables them to advance their interests. We need to be focusing on new technologies: hypersonics, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and what exactly will be the command and control for all these systems.

I think we definitely need to be answering that question, and I don’t know what the right budget number is. I think this is, at the end of the day, the key conflict that I have with the progressives at the moment. They are very aggressive about saying the Department of Defense is spending too much money, and they make some decent arguments about that. But I’m trying to answer the question, where in the defense budget, what money ― not just, “$738 billion is ridiculous, it should be $650 billion.” Well, what $80 or $8 billion do you cut? We have to be able answer that question while still maintaining a reasonable national security policy ― and I think a huge part of answering that question, getting to that question is employing new technologies.

We can deter Russia and China from means other than having more missiles. We can deter them from having more allies, more friends. Look at Iran: What would stop them from exporting revolution and malign influence in the Middle East? What would stop them is if they didn’t have fertile ground in Lebanon, in Yemen, in Iraq ― if they went there and people said: “We don’t want what you’re selling.” That has less to do with military hardware than good governance and good economics. All of those questions swirl around coming up with a coherent national security strategy.

The marquee provision in the NDAA, at least for the White House, was the Space Force ― and that idea was widely mocked at first. But the next commander said that it’s nationally critical. Why was Congress conflicted about this idea, and should it have been?

It should have been. They were conflicted because, if you look at the policy ― and space is essential to the the weapons systems we were just talking about ― everything we do these days is dependent upon satellite communication. And if you don’t have some control over space and control the satellites you’re launching, your ability to take care of them, it’s a huge problem.

There was bipartisan concern about the efficiency and effectiveness of the way the Air Force was doing it. Space Force was one way to fix it, by putting a greater emphasis on space within the greater construct of DoD ― and if you do that and you’re only creating more bureaucracy, you’re making it worse. That was the conflict.

[Alabama Republican Rep.] Mike Rogers and [Ohio Republican Rep.] Mike Turner were the two sides of that argument when our committee took it up two years ago. Both sides made passionate arguments, and it was Republican on Republican. Ultimately, Jim Cooper, who’s our lead [for the Strategic Forces Subcommittee], agreed with [the subpanel’s top Republican], Mike Rogers, who felt that Space Force made sense.

On the politics, even though the idea started on the House Armed Services Committee, for whatever reason, the president glommed onto it and talked about it in the way the president talks. A lot of people who weren’t familiar with the debate looked at that and thought: “Seriously, he wants a Space Force because he likes the name?” I cannot honestly speak to the president’s motivations. I do know what Jim Cooper and Mike Rogers have been working on ― and ultimately, I defer to the wisdom of my subcommittee chair and ranking member.

So yeah, it got caught up in Donald Trump’s politics, but this was a bipartisan idea. There was bipartisan support and bipartisan opposition. That this was the president’s idea, and he forced us to accept it is simply not correct.

It seemed like this bill leans fairly heavily in the direction of military personnel with the housing provisions and troop pay raise. Do you see Congress further heading in that direction with the next bill, or are we going to see, say, your acquisition reform proposals?

Making sure smart, capable people want to come to work for the federal government is really important. Paid parental leave was a crucial step; just as it is more broadly in the federal government, personnel at DoD is crucial. We will continue to make sure we can maintain and attract the best personnel.

On acquisition reform, I’ll put out there it’ll be a huge priority for me. I’m a big believer in competition and commercial off-the-shelf technology. We need to make sure we encourage as many competitors as possible. I’m thinking of small businesses that might be intimidated by the bureaucracy and able to offer the ideas that they have, thus reducing the competition for goods and services that can help the military.

Another way to encourage competition is to speed up decision-making. Technology is really rapid, and if we’re going through two-, three-, four-, five-, 10-year cycles to buy anything because we’re going through the normal program of record, [request for proposals] bullshit, that’s a problem. I want to empower people at DoD to purchase the best technology right now. Keep it simple: Buy the thing that’s going to work now. And the committee is going to pursue that type of reform.

Joe Gould was the senior Pentagon reporter for Defense News, covering the intersection of national security policy, politics and the defense industry. He had previously served as Congress reporter.