WASHINGTON — The Pentagon’s program to upgrade the F-35′s engines could start to run out of money early next year if a budget is not passed in time, officials told lawmakers Tuesday.

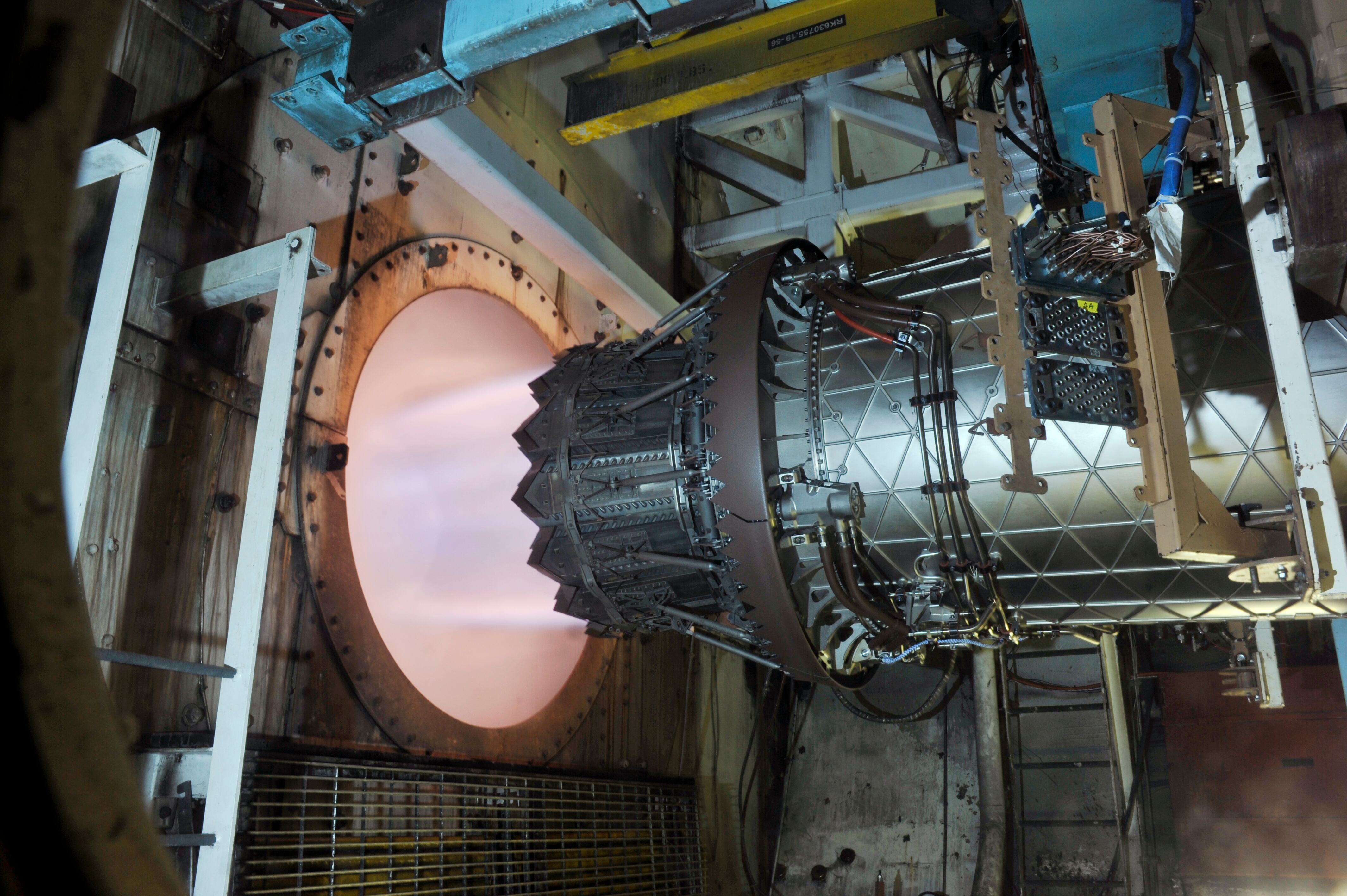

The Engine Core Upgrade program, which seeks to give the fighter jet’s current Pratt & Whitney-made F135 engines more power, thrust and cooling ability, has enough money to last through roughly February, F-35 program executive officer Lt. Gen. Michael Schmidt said in a hearing before the House Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces.

But beyond that, “if we don’t get appropriations, I’m in a rough spot in a couple of months,” Schmidt said.

The Pentagon budgeted $75 million for the Engine Core Upgrade, or ECU, program for fiscal 2023; its proposed budget for fiscal 2024 would increase that to more than $400 million.

But since the new fiscal year began two and a half months ago, the Pentagon has operated under continuing resolutions that keep funding programs at 2023 levels. This has meant the ECU program has not yet received its expected budget increase and is now limited to last year’s funding, Schmidt said.

“We’re supposed to be ramping up [spending in ECU] significantly this year,” Schmidt said. “We’re capped at that level, and then we’re actually at risk of it running out if we don’t have an appropriation soon.”

Pratt & Whitney declined to comment to Defense News on how another continuing resolution would affect the engine program’s timeline or budget.

The engine core upgrade and its greater power and cooling ability is needed to allow future modernizations for the F-35, particularly the upcoming improvements known as Block 4. Those upgrades will allow the jet to carry more weapons, new sensors, and better electronic warfare and target recognition capabilities.

The Pentagon expects to start issuing the first in a series of sole-source contracts to Pratt & Whitney in the second quarter of fiscal 2024, and continue through the end of 2031. A company executive in December 2022 estimated the cost of ECU’s development at $2.4 billion.

Schmidt told reporters after the hearing that running out of money would be “not good at all” for ECU’s ability to stay on schedule, though an exact timeline is not set because the program is in its nascent stage.

Pratt & Whitney said in November it wants to start delivering ECU’s increased power capabilities in 2029. But Schmidt said Tuesday he’s unsure whether that date is feasible, adding that the program has not yet reached the engineering and manufacturing development phase.

“If [my director of propulsion] told me I’m going to field in October of [20]29, I’d be like: ‘You’ve got 1,000 things to prove to me before I’m signing up to that date,’ ” Schmidt said.

Pratt & Whitney expects to finish ECU’s preliminary design in December 2023, and noted the government’s review will take place about a month later.

Schmidt also raised concerns about the effect on Pratt & Whitney’s workforce of 600 that it assigned to the engine upgrade project. If the firm lost engineers due to a lack of funds, Schmidt said, it would be difficult to replace those employees.

“Especially in the environment that we’re in today, engineers are a premium” skill set, Schmidt said. “We have to make sure we keep them — not just at Pratt, I’m talking across the board. These [continuing resolutions] are a significant impact to the [Defense Department]. When we lose people … whether it’s in the government or in industry, getting them back is really, really hard.”

Bill LaPlante, the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, told lawmakers that the Pentagon may have to rethink its funding strategy for ECU if money starts to run out early next year.

A related effort to upgrade the F-35′s power thermal management system, which would allow future improvements to the aircraft, is also sorely in need of increased funding to begin, Schmidt said. That technology uses the “bleed air” from the F-35′s engines to cool systems such as weapons and radar.

Rep. Carlos Gimenez, R-Fla., questioned the Pentagon’s decision to upgrade the F-35′s current engines instead choosing a new, so-called adaptive engine for the jet. GE Aerospace created such an engine, the XA100, under the Adaptive Engine Transition Program, which the Pentagon seriously considered for the F-35.

“If I’m in the jet and I’m the fighter pilot, I want the engine that takes me faster and takes me longer,” Gimenez said.

While LaPlante noted the Adaptive Engine Transition Program’s technology successfully delivered a 30% improvement in engine efficiency, and that he hopes developments continue, the department could not afford to fund an engine that it was only certain could work in the Air Force’s F-35A variant.

The Pentagon concluded GE’s engine would not fit in the Marine Corps’ F-35Bs and may not fit in the Navy’s F-35Cs, thus the department chose the F135 upgrade.

Logistics in jeopardy

The Pentagon has also paused negotiations with F-35 manufacturer Lockheed Martin on a performance-based logistics deal for the aircraft, after costs came in higher than expected and time started to run out on extending a standard sustainment contract.

Lockheed Martin has for years pushed for such a performance-based logistics deal, or PBL, saying it would save the government money, quicken repairs and increase the availability of spare parts. PBL deals mean contractors are paid on expected performance outcomes, not for discrete parts and services, as occurs under a typical transactional contract.

But before the Pentagon can enter into such a contract, lawmakers in 2022 required it to first show a PBL would either lower costs or improve aircraft readiness over the current annual sustainment contract for the F-35.

This current contract, which covers 2021 to 2023 and was originally worth up to $6.6 billion, has already been extended through March 2024, LaPlante said, and another extension to bring the contract through next June is in the works.

LaPlante added that the PBL proposal Lockheed submitted in June 2023, and then updated in October, didn’t hit the desired cost or performance targets. He also said tabletop exercises on sustainment in the Pacific region have shown that a PBL deal would need to be able to surge capability to the region in an emergency.

In a statement to Defense News, Lockheed said it is “disappointed” with the Pentagon’s decision, but pledged to keep working with the government and other F-35 customers to deliver the sustainment support and mission readiness they need.

“We continue to view performance-based logistics contracting as the primary way to increase part availability, readiness and affordability for the long term as the F-35 fleet scales,” Lockheed added.

Lockheed said it is still talking to the Pentagon about a potential PBL contract. But in case a deal can’t be reached, the company noted, it is working on an alternate deal that would take effect beginning July 2024.

When asked if that might be an updated version of the standard sustainment contract, Lockheed said it could not offer further details, but it is working with the JPO to figure out what the alternate contract solution would look like.

In his testimony, LaPlante did not close the door on striking a PBL deal with Lockheed, but noted his negotiations team had to shift focus and concentrate on extending the current contract to keep sustainment activities going.

“About a month ago, it was clear we were not going to get a [satisfactory] cost proposal with the performance that we’d feel comfortable with,” LaPlante said. “Simply, we were not going to approve a PBL that did not perform well and didn’t get the cost savings.”

“We have not given up on it, but we’ve got a lot of work to do there with industry,” he added.

For a PBL to work, LaPlante explained, it must last at least five years. Finding ways to measure how well a contractor is living up to its end of the bargain can also be tricky, he noted.

“Sometimes at the system level, performance-based logistics is very hard to do … if the contractor themselves or the program office doesn’t have control over the metric” used to evaluate performance, LaPlante said.

He added that the government plans to push for more of the F-35′s data from Lockheed Martin as part of its PBL negotiations.

Schmidt also said the F-35 program is closing in on a milestone C decision on full-rate production on the jet, now that a series of Joint Simulation Environment tests are finished. Those trials aimed to replicate complex, real-world scenarios the F-35 is likely to encounter in combat. The data will help LaPlante make the official decision on full-rate production, which he expects in March 2024.

However, Lockheed is already building F-35s near full capacity, meaning the effect of a full-rate production decision is likely to be muted.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.