WASHINGTON — The Marine Corps acknowledged Thursday it had misidentified one of the six men in the iconic 1945 World War II photo of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima.

The investigation solved one mystery but raised another. The Marine Corps investigation identified a man who has never been officially linked to the famous photo: Pfc. Harold Schultz, who died in 1995 and went through life without publicly talking about his role.

"Why doesn't he say anything to anyone," asked Charles Neimeyer, a Marine Corps historian who was on the panel that investigated the identities of the flag raisers. "That's the mystery."

"I think he took his secret to the grave," Neimeyer said.

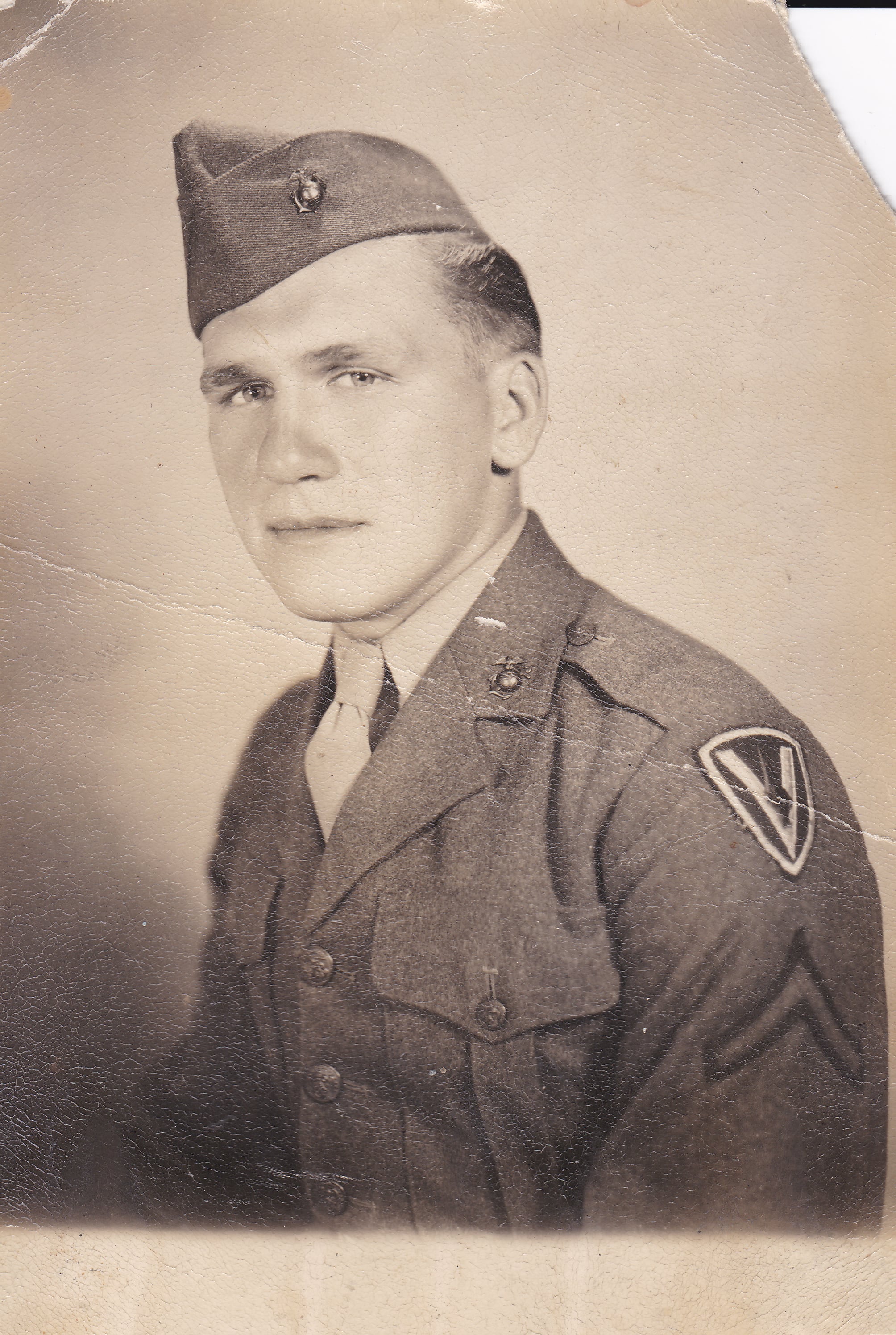

U.S. Marine Corps Pfc. Harold Schultz

Photo Credit: Courtesy of The Smithsonian Channel

The Marine Corps investigation concluded with near certainty that Schultz was one of the Marines raising the flag in the photo.

The investigation also determined that John Bradley, a Navy corpsman, was not in the photograph taken on Mount Suribachi by Joe Rosenthal, a photographer for The Associated Press. The Feb. 23, 1945, photo that has been reproduced over seven decades actually depicts the second flag-raising of the day.

The three surviving men identified in the photo, John Bradley, Ira Hayes and Rene Gagnon, went on a tour selling war bonds back in the United States and were hailed as heroes.

Bradley's son James Bradley and co-author Ron Powers wrote a best-selling book about the flag raisers, "Flags of Our Fathers," which was later made into a movie directed by Clint Eastwood. John Bradley had been in the first flag-raising photo on Iwo Jima and may have confused the two, Neimeyer said.

Schultz, who enlisted in the Marine Corps at age 17, was seriously injured in fighting on the Japanese island and went on to a 30-year career with the U.S. Postal Service in Los Angeles after recovering from his wounds. He was engaged to a woman after the war, but she died of a brain tumor before they could wed, said his stepdaughter, Dezreen MacDowell. Schultz married MacDowell's mother at age 63.

Analysts believe Schultz, who received a Purple Heart, knew he was in the iconic image, but chose not to talk about it.

"I have a really hard time believing how it wouldn't have been known to him," said Matthew Morgan, a retired Marine officer who worked on a Smithsonian Channel documentary on the investigation. The filmmakers turned over their evidence to the Marine Corps to examine.

Schultz may have mentioned his role at least once. MacDowell said she recalls he said he was one of the flag raisers over dinner in the early 1990s when they were discussing the war in the Pacific.

"Harold, you are a hero," she said she told him.

"Not really. I was a Marine," he said.

She described him as quiet and self-effacing.

It's difficult to fathom his desire to keep his role quiet in an era when many Navy SEALs and other servicemen are rushing books into print about their exploits. During WWII many veterans were reluctant to speak about their experiences because it reminded them of the horrors of war.

One of the flag raisers, Ira Hayes, initially asked to remain anonymous, but the Marines were under orders from President Franklin Roosevelt to identify the Marines so they could go on a war bonds tour.

The photo appeared in thousands of newspapers and raised the morale of a nation that had grown weary of the bloody slog in the Pacific.

"We were winning the war but it was the hardest part of the war," historian Eric Hammel said of the Pacific island-hopping campaign.

"It went viral in the 1945 equivalent of the word," Neimeyer said.

The new investigation was prompted by growing doubts about the identity of Bradley in the photo.

Two amateur historians, Eric Krelle and Stephen Foley, went further and were able to identify Schultz as a possible flag raiser. They examined the Rosenthal photo and compared it to others taken the same day, including a video that was shot at the same time as Rosenthal took his photo. Their research was highlighted in a lengthy 2014 Omaha World-Herald article.

More than a year later the Marine Corps agreed to investigate the claim, appointing a nine-person panel headed by Jan Huly, a retired Marine Corps three-star general.

The faces in Rosenthal's photos are mostly obscured, but investigators were able to identify distinctive ways the Marines wore their equipment and uniforms in the photo and then compared it to other photos taken of the unit on the same day.

"It's obvious to the untrained eye," said Michael Plaxton, a consultant who examined the photographs for a documentary, "The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima," which will air on the Smithsonian Channel on July 3.

"People have pointed out the inconsistencies over the years," Plaxton said.

He said it required more careful and independent analysis to draw any firm conclusions, however. Plaxton's report and other material uncovered by the Smithsonian Channel was used by the Marine Corps in their investigation.

Neimeyer said the Marine Corps didn't immediately launch an investigation because it frequently received competing claims about the presence of people in famous war photos. Once the Marine Corps realized how compelling the evidence was in this case, it agreed to look into the issue earlier this year.

It wasn't the first time the Marines had to correct the record. A Marine Corps investigation in 1947 determined that Henry Hansen had been misidentified as a flag raiser instead of Harlon Block. Both men had been killed in action on the island, as were two other men identified in the photo, Franklin Sousley and Michael Strank.

It's not surprising there has been confusion about the identities of the Marines. Rosenthal gave the shot very little thought as he took it, and the men raising the flag took little notice as well.

The Marine Corps effort to identify the men was further hindered by the confusion over the fact there were two flag-raisings, the chaos of one of the war's bloodiest battles and the faces in the photos were obscured.

The Marine Corps said the results of the investigation don't undermine what the photo and memorial depicting it represent. The photo helped cement the Marines' reputation as one of the world's toughest fighting forces.

Marines landed on Iwo Jima, a tiny Pacific atoll about 760 miles from mainland Japan, on Feb. 19, 1945, beginning a bloody five-week fight for every inch of the island against an entrenched Japanese force that refused to surrender.

Few Marines escaped unscathed. Of the 70,000 Americans who participated in the battle, 6,800 were killed and about 20,000 were wounded. Some infantry units sustained much higher casualty rates. About 20,000 Japanese soldiers, most of the force, died trying to defend the tiny island.

The first flag-raising, which occurred shortly after 10 a.m., captured the attention of the Marines fighting on the island. In the midst of brutal battles throughout the island they looked up to see the flag flying over Mount Suribachi, the highest point on the island. Marines paused to cheer. Navy ships sounded their horns.

Hours later the Marines decided to replace that flag with a larger one. Rosenthal was there, snapping a photo so quickly he didn't have time to look through his viewfinder.

After Schultz's death, MacDowell found only a few items that her stepfather kept from his Marine Corps days. Included in the metal box of military records was a group photo that Rosenthal took of Marines on Iwo Jima around the same time as the famous photo.

But there was no answer to the mystery of why Schultz remained largely silent about his brush with history.

"He probably wouldn't be really happy with us revealing this now," Neimeyer said.