Editor's note: This story first appeared in the July 15, 2013, edition of Marine Corps Times. ![Marine Corps Museum grows to showcase Corps legacy [image : 25423299]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/bff999dc09cdb072d488e86c41110a6e346369d4/c=1562-0-4987-2927/local/-/media/2015/04/07/GGM/MarineCorpsTimes/635640202398448201-1848058.jpg)

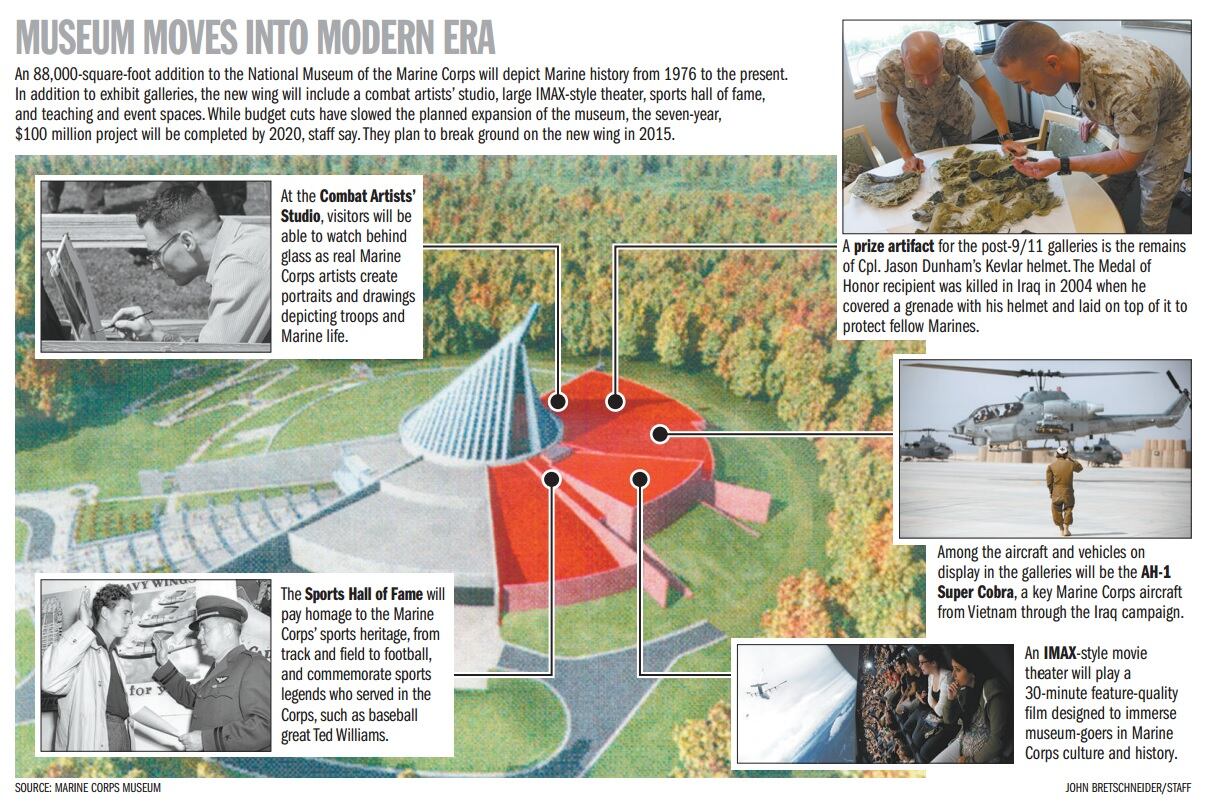

TRIANGLE, VA. — The National Museum of the Marine Corps is launching a seven-year $100-million project to document the service's history from the end of fighting in Vietnam to this generation's conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

To do so, its facility on the outskirts of Marine Corps Base Quantico will nearly double in size, growing from 112,000 square feet to 200,000 square feet by 2020. The expansion will come in stages and feature the addition of an IMAX-style movie theater, refurbished aircraft and combat vehicles along with a host of new exhibits.

Construction of the new wing is scheduled to begin in 2015, museum staff say. By 2017, they expect to open the theater and a military art gallery. The following year, two permanent galleries are scheduled to open covering Marine history from the 1980s to the present. A gallery showcasing key events between conflicts is set to open in 2020 along with rotating exhibit space.

Exhibits will cover Marine missions in Panama and Grenada, the deadly barracks bombing in Beirut, Lebanon; operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield; and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The new wing also will house a host of authentic artifacts used during this period, including a refurbished F/A-18 fighter jet, an AH-1W Super Cobra helicopter, an M60A1 tank, an MRAP-All Terrain Vehicle, drones and more.

Visitors will be able to watch combat artists draw and paint in the studio, feel the concussion of grenade blasts in immersion galleries and view a 30-minute feature-quality film about Marine Corps history and culture.

The phased approach

The museum opened in 2006 with 200 years of Marine Corps history depicting America's 911 force from the American Revolution to Vietnam. The decision to do so at partial completion was deliberate, said spokeswoman Gwenn Adams, and made in part so the nation's oldest Marine veterans would have a chance to see their history on display while they still have the opportunity.

"The guys who had fought in World War I certainly weren't coming to a museum at that point," Adams said. "But the World War II guys continued to come," holding numerous reunions surrounded by mementos of their shared history.

Money is another issue. The museum is the product of a public-private partnership; the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation raised $60 million to build and open the facility, while the Marine Corps contributed $42 million in public funds to populate the exhibits and galleries.

This next phase requires an additional $34 million from the Marine Corps at a time when spending is being reined in across the federal government and sequestration — massive across-the-board cuts triggered in March after Congress failed to reach an agreement on how to address the federal deficit — threatens even mission-essential programs. That has slowed planning, said Lin Ezell, the museum's director.

"Because this is a big number over a multiyear period, we were able to work with [Marine Corps] headquarters to spread out the funding over several years, so there wasn't one big spike," she said. "It is a hard time to sell a new start. But all of the general officers have been incredibly enthusiastic, and they see the benefit of a museum that takes the story up to the present day."

Collecting artifacts

While curators relied on life-size cast figures and authentic uniforms to tell Revolutionary War history and oral accounts and grainy video to tell that of World War II, they will have the advantage of modern media — digital photos and videos made by Marines on the battlefield — to tell the present-day story. Chuck Girbovan, the museum's exhibit services chief, said the plan is to curate some of the best user-generated content, and possibly even one or two of the famous "bored Marine videos" that have given the world a backstage look at Marine goofiness and camaraderie during downrange downtime.

Girbovan said the museum may also feature elements of the cutting-edge urban-warfare training that has been developed in recent years, such as the infantry immersion trainers that attempt to replicate conditions in Afghanistan down to costumed role players, market sounds and barnyard smells.

The museum does not solicit donations. It receives most of its artifacts from veterans or military family members who want to part with their military items but preserve the history they represent.

While curators receive an abundance of World War II-era weapons, uniforms and trophies, they've found many veterans of the most recent conflicts are not ready to part with their mementos. For Marines and veterans who might be willing to help them tell the next phase of the story, Girbovan cautioned that curators are looking for items that have a "back story," that advance the historical narrative.

One prize artifact for the new wing is the fragmented helmet of Cpl. Jason Dunham, who received the Medal of Honor posthumously in 2007. Dunham was killed in Iraq in 2004 when he covered a live grenade with his helmet and laid on top of it to protect fellow Marines. The Kevlar muted some of the blast, but left Dunham with fatal wounds.

"That we have that is huge because there's so many stories you can tell from that," Adams said. "How strong is the Kevlar? How far will a Marine go to save his fellow Marines? All these stories you can tell from that one artifact."