As Marines gather to celebrate the Corps' 240th birthday, chants of "oorah!" are likely to be heard around the world. That iconic battle cry is just one mark of the long-lasting legacy left by the oldest living sergeant major of the Marine Corps has left on the service. The oldest living Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps is a living legend of sorts.

When retired Sgt. Maj. John R. Massaro, born in the Depression era, left his hometown of Cleveland to enlist in the Marines in 1948, he didn't think it would turn into a career. About 29 years later — after combat tours in Korea and Vietnam and high-profile assignments in Washington — the career infantryman was named the eighth sergeant major of the Marine Corps before retiring ended up spending more than three decades in the Marine Corps. starting a career that stretched three decades, took him to combat zones in Korea and Vietnam and culminated as the top enlisted Marine before his retirement in 1979.

As another Marine Corps birthday week comes to a close, Massaro, now 85, spent it the same way the week doing what many This year, Massaro is spending the Marine Corps Birthday week as many Marines do: Rreminiscing and reconnecting with old friends and battle buddies.

"I was blessed," he said, speaking by phone from Utah. "I try to sit back and look. The hand of Providence guided me where I went."

After leaving the Marine Corps, Massaro moved to Utah where he worked for Veterans Affairs in Salt Lake City for about three years. Now fully retired, Massaro splits his time between two homes in Utah, one in Orem and the other in St. George.

He has outlived two wives and stays busy with his son and extended family that includes grandchildren and lifelong friends he's met in the Marine Corps. While he no longer laces up for daily runs, he still maintains his retirement weight at 178 pounds and goes on walks twice a day with his Boston terrier, Azula, and his son.

Retired Sgt. Maj. of the Marine Corps John Massaro, 85, now lives in Utah with his Boston terrier, Azula.

Photo Credit: John R. Massaro

That, he says, keeps him active, sharp and full of life.

Massaro's biography would get the attention of any Marine, but one thing in particular is likely to stand out. Official service anecdotes credit him with popularizing "oorah" in the Marine lexicon — and that alone has cemented him into leatherneck lore.

Finding camaraderie

Massaro was just a teenager when World War II ended. Like many in his generation, he decided to enlist in the Marine Corps.

After graduating from Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, Massaro was assigned to 1st Battalion, 6th Marines — then designated as 1/5 — out of Camp Pendleton, California. After a short stint there, Massaro left for a 10-month assignment in 1950 with the Marine Barracks in Clearfield, Utah, home to a naval supply depot.

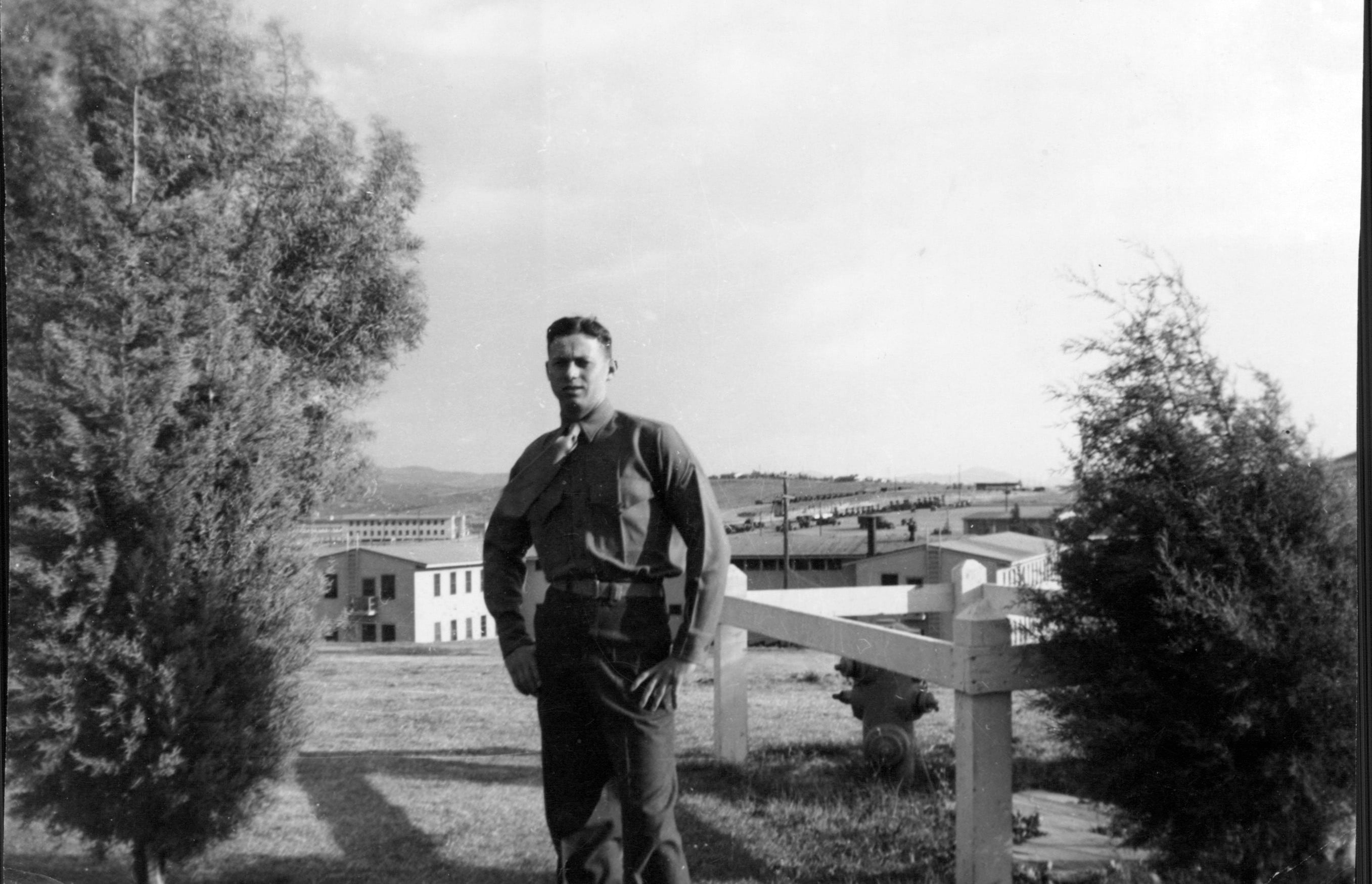

Retired Sgt. Maj. of the Marine Corps John Massaro shown here near Camp Pendleton Calif., in 1948.

Photo Credit: John R. Massaro

From there, he got orders to the drill field in San Diego. Since there was no drill instructor school at the time, Massaro said where he learned how to train recruits on the fly and self-studied what he'd teach his recruits.

While it wasn't an assignment he chose, but he was determined to do it well. Massaro didn't ask to be a DI.

"Back in those days, you just went where they sent you," he said. "Nobody ever complained. You'd stay up all night after you'd put your recruits in the bunks. You would study up and you'd teach what you had to do."

Those tours in Utah and MCRD San Diego tours profoundly influenced his decision to become a career Marine. for a career in the Marines. He made some of his several lifelong friends during those assignments. among the tight-knit, 86-member Marine Barracks. "You got to know all of them.

"The camaraderie of the Marines was really special," he said.

A few years later, Massaro returned to MCRD San Diego for a second drill instructor tour. About a decade later, he did a third.

Over time, Massaro saw boot camp change drastically. Tighter regulations were put into place following the 1956 Ribbon Creek incident at Parris Island that left six recruits dead after their drill instructor led them into a swampy tidal creek. By his third DI tour, there was far more supervision at Marine recruit depots, with chief DIs and series officers overseeing platoons.

"I think it was all for the better," said Massaro, who served as chief drill instructor with E Company, 2nd Recruit Training Battalion. "It really took some of the pressure off of the drill instructors because you had somebody else who was responsible for certain aspects of the training."

Off to combat

Before his second DI tour, then-Sgt. Massaro rode a transport ship to Korea in 1952, where he ith the 23rd Replacement Draft and was assigned to H Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. As they crossed the Pacific Ocean, his His biggest worry? His end-of-service date had just expired crossing the Pacific.

The battalion sergeant major told Massaro they'd get him on the first available transport back to the U.S., but the future sergeant major of the Marine Corps wasn't having it.

"I said, 'I didn't come 7,000 miles to turn around and go back,'" he said. "Long story short, I extended for three years." For that, he got a $200 bonus, paid out over four years, which he promptly sent home to his wife.

Many of the Marines would see their first combat zone. On ship, they played pinocle, tended their rifles and inspected their shipboard spaces. Massaro wasn't fearful. "Marines don't worry about that kind of stuff. You just took it one day at a time," he said. "All Marines really expected was three square meals and a place to sleep."

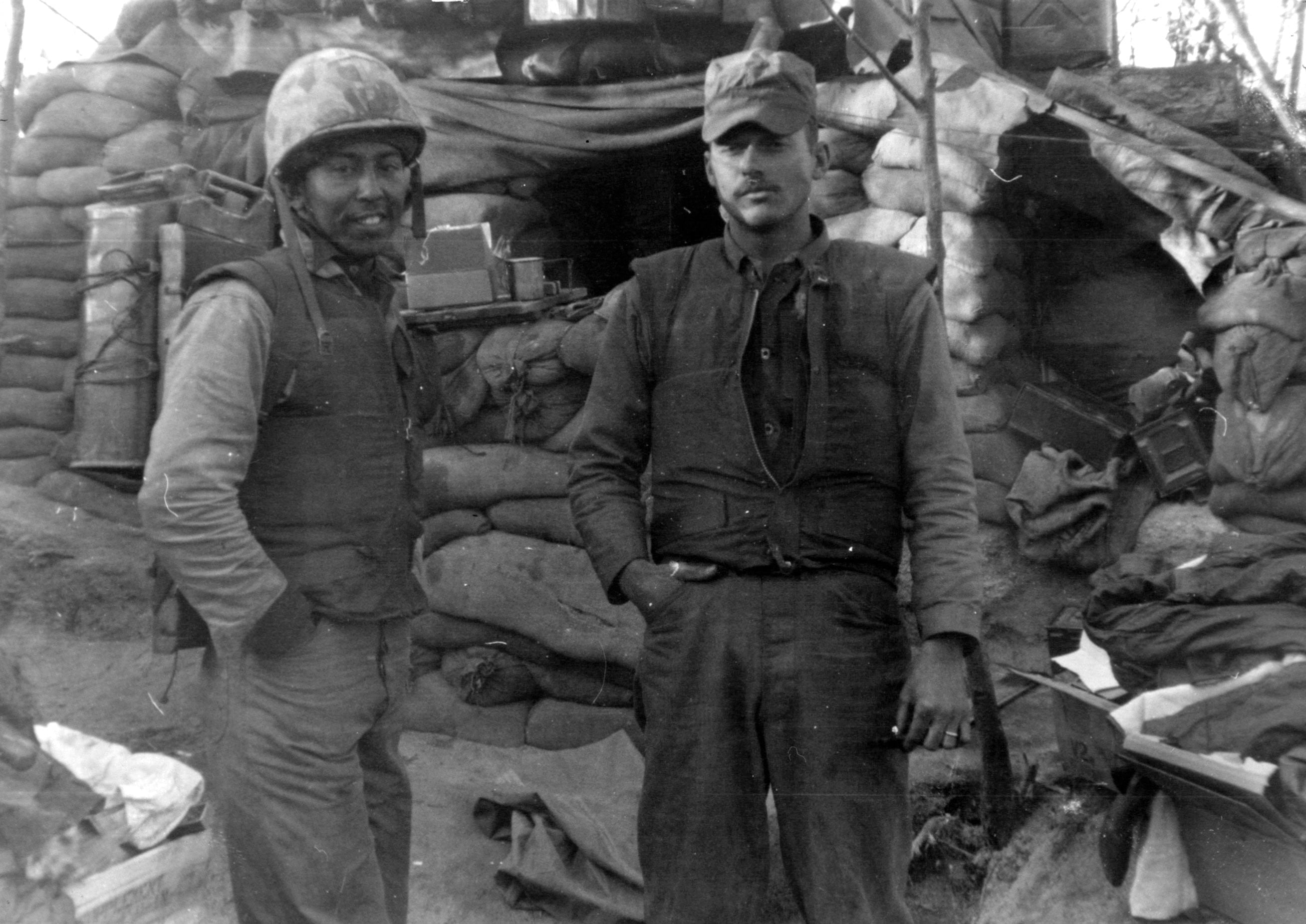

Retired Sgt. Maj. of the Marine Corps John Massaro said his first enlistment expired on his way to the Pacific in 1952, but he refused to go home and instead re-upped for three years. In this photo, Massaro and his fellow Marines are in Korea.

Photo Credit: John R. Massaro

In Korea, he led H Company's second platoon and a 60mm mortar section. Contact by the enemy often came at night.

"One night on patrol, the guy in front of me stepped on a mine and lost both of his legs," he recalled. "The guy behind me got hit in the face. I never had a scratch on me."

Nearly a decade before he becoming the eight sergeant major of the Marine Corps in 1977, then-1st Sgt. John Massaro, center and shirtless, helped build a septic tank alongside members of 3rd Engineer Battalion in Vietnam.

Photo Credit: GySgt Anthony J. Valys/Marine Corps

Years later, Massaro landed in Vietnam and was assigned to 3rd Engineer Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. Then a sergeant major-select, he had sought a reconnaissance billet in Khe Sanh, but was assigned to the engineers instead.

In January 1968, he and his Marines drove their trucks through Hue City while en route to Vietnam's Quang Tri province. What they didn't know at the time was that North Vietnamese army and Viet Cong forces were nearby and would launch the start of the Tet Offensive in Hue City the following day.

"We didn't have any extra ammo or nothing," Massaro recalled. "Where they were positioned, they probably could have wiped us out in 30 seconds."

Coining a battle cry

It was in the mid-1950s, though, when Massaro might have left his longest lasting mark on the Marine Corps.

As a company gunnery sergeant with 1st Marine Division Reconnaissance Company aboard the submarine Perch, Massaro and his men got in the habit of saying "oorah" while imitating the sub's klaxon horn that sounds off as "arrugah."

While there are several theories about the origins of the saying, some Marine Corps historical references suggest that Massaro carried the popular phrase into his drill field tours after his days aboard that sub.

"It became some kind of greeting, when you saw one of your shipmates or one of your Marines, instead of saying, 'How are you?'" Massaro said. "It kind of got passed around. It was used as a chant, when people were running."

Retired Sgt. Maj. of the Marine Corps John Massaro, right, was the company gunnery sergeant when 1st Marine Division Reconnaissance Company was aboard the submarine Perch. Some say that's where the phrase "oorah" originated.

Photo Credit: Courtesy John R. Massaro

"Oorah" has become a battle cry for the generations since, a phrase symbolic of the Marine Corps as much as "leatherneck" and "devil dogs." Some historic references cite Massaro's tour at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego as the place "oorah" really caught hold when he began using the phrase with new recruits.

Massaro, for one, is baffled why he's credited with the word. "I don't take credit for it," he said, chuckling. "It was a phrase or a term originally coming from boarding a ship."

Climbing the ranks

Massaro calls his recon assignments "a blessing," and credits them with enhancing his career. But he also thrived on assignments outside of his comfort zone as an infantryman.

In 1959, he got his first wing assignment as the administrative chief with Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron 1 in Japan. With more than 1,000 personnel, it was the Corps' largest squadron.

About a decade later, Massaro became Recruiting Station San Francisco's top enlisted leader. While the anti-war sentiment was high across the country during that time, he said the recruiters he led were well supported by their local communities, and they were able to meet their quotas.

In the early 1970s, Massaro was sent back to Japan for his second wing assignment as Marine Aircraft Group 36's sergeant major. With squadrons deployed around the region, it was a busy time, he said. After about a year there, he received orders to report to Marine Corps Headquarters to serve as the sergeant major to the Inspector General of the Marine Corps. The two-year assignment kept him and his boss on the road, running together when they could and seeing Marines in places like Iceland, Europe and South America.

It was also his first foray into the Marine Corps' inner workings. When tasked with briefing the commandant, he said he had to "just tell it like it was." Sometimes that meant relaying good news and sometimes bad, he said.

Massaro would go on to serve a short stint as station sergeant major for Salt Lake City Recruiting Station before becoming the 1st Marine Division sergeant major. He had spent more than one-third of his career with the storied "Blue Diamond" Division.

Then he learned the 26th commandant, Gen. Louis H. Wilson Jr., had selected him as the eight Marine to be the sergeant major of the Marine Corps. Massaro said he was shocked.

"I really didn't think I had a chance," he said. "To be selected above [some of the other well-qualified contenders] was a humbling experience."

Massaro held the position from April 1, 1977, to Aug. 15, 1979, working mainly for Wilson and briefly for Gen. Robert H. Barrow.

"You are there as the eyes and ears for the commandant," he said. "You are there to serve the commandant for whatever capacity."

Massaro was tasked with going out into the field to talk with other sergeants major and Marines. During one of those stops, Massaro met some young Marines at a bus stop near the Pentagon — including the future 16th Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Carlton Kent.

At the time, Kent and the other Marines were waiting for a ride to attend a French class. They were training for Marine security guard duty, and Kent said he was struck by Massaro's commitment to his junior Marines.

"He'd take the time to talk to us — and no, not just a few minutes, [but] 15 to 20 minutes," Kent said. "He'd ask us, 'You have any questions for me?' We were just staring at him, and said 'Oh no, sergeant major.' You've got the eagle, globe and anchor with two stars looking at you."

That experience that helped mold Kent's own approach when he became the Corps' top enlisted Marine in 2007.

"When the commandant and I talked about making decisions about the Marine Corps, we just went out to the Marines... and got input from the Marines, especially the leadership on the ground."

Kent called Massaro a mentor and a true motivator of Marines.

"[He] is a gentleman, but if you put him in battle, he's definitely a war fighter," Kent said, "He is every bit Semper Fidelis."