The Marine Corps is refining its new concept of operations — Expeditionary Force 21 — as it begins to apply the new doctrine to real-world missions and large-scale military exercises, a Marine general told a gathering of Naval officers Wednesday.

That could include basing mini special-purpose Marine air-ground task forces on small ships in the Pacific and the Gulf of Guinea to quell criseis on a moment's notice, said Maj. Gen. Andrew O'Donnell, the deputy commanding general for Marine Corps Combat Development Command, at this year's Annual Surface Navy Association symposium in Arlington, Virginia.

The major tenets of EF-21 and the closely related Marine Expeditionary Brigade Concept of Operations, which together place an emphasis on scalable forces built and deployed within hours of a crisis, are sound, he said.

But service leaders are now weighing the nature of distributed operations, studying after action reports — most recently from Bold Alligator 14 — and carefully considering how current and future amphibious and air platforms will influence how the doctrine is applied to meet unpredictable missions in a post-Afghanistan operating environment.

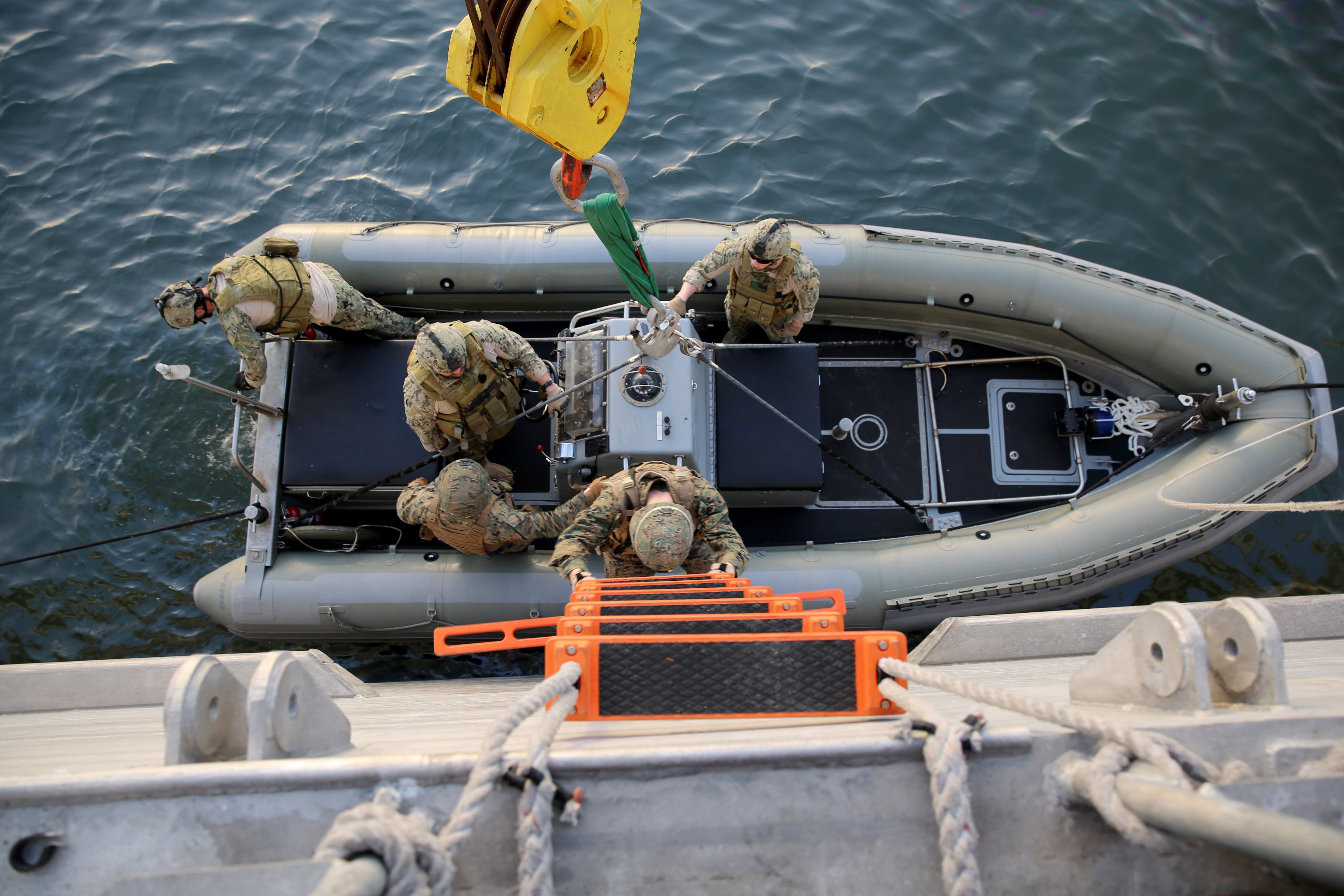

Marines board a rigid-hull inflatable boat from the Joint High-Speed Vessel Spearhead. Marines tested the JHSV during Exercise Bold Alligator.

Photo Credit: Sgt. Ed Galo/Marine Corps

"The operating environment that we live in today has obviously changed," O'Donnell said. "It is based more on poor governance, bigger gaps between the haves and the have-nots, increases in unrest and instability, along with proliferation of advanced weapons. Certainly this requires a demanding response across the range of military operations."

Ship-board crisis response units

To meet those challenges, the service could put a small mini special purpose MAGTF Marine air-ground task force on the next generation LXR amphibious ship. While the ship — based on the hull of a the Navy's current San Antonio-class LPD-17 amphibious transport dock ships — has space for two fewer landing craft air cushions, it has a much larger flight deck, O'Donnell said.

That provides more capability with air assets, which is significant he said, because Marine forces will be able to disaggregate for distributed operations.

That means it could be used as a "single deployer" floating on its own with a crisis response unit aboard. That closely mirrors comments made by Lt. Gen. Kenneth Glueck, commanding general of Marine Corps Combat Development Command, who said in September that in 2015 he would explore the possibility of placing crisis response units on Navy mobile landing platform ships.

It give Marines a faster response time when carrying out missions like the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy in Juba, South Sudan, about a year ago, or the one in Libya in July. The Marines For those, they had to deploy from Móron, Spain. While they were able to successfully complete their missions, they had to fly long distances to do so. the large distances they had to cover using MV-22 Osprey and KC-130J Super Hercules refueling aircraft cost them precious time.

Distributed operations, as implied by the theme of this year's symposium — Surface warfare: Distributed Lethality, Going on the Offensive — will define the Marine Corps' future.

The ship-to-shore dilemma

While Iraq and Afghanistan provided a measure of predictability in the type and frequency of operations — as well as the size of the battlefield — Marines are units are increasingly likely to find themselves fighting as smaller units spread across hundreds of miles or even multiple islands, as the case may be in the Asia-Pacific region.

With the return of the possibility of amphibious assault missions, the service is working to solve its ship-to-shore dilemma. The proliferation of cheap but threatening missile technology, even among non-state actors, means that Navy ships must remain further than ever off from shore to provide sufficient time to deploy counter measures against missile attacks.

That has left the Marine Corps without a ship-to-shore connector that can bridge the gap in a reasonable amount of time. The Amphibious Combat Vehicle now in the works has a displacement hull, meaning it slowly pushes its way through the water unlike the now defunct Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle, which would have quickly skimmed across the surface of the water. From current ship standoff distances, it would take hours for Marines to get swim ashore on the ACV without another connector.

To solve that dilemma, the service is in part turning to the joint high-speed vessel. The idea is to land in an uncontested area beach or in a harbor unopposed on an uncontested beach or in an uncontested harbor and then assault towards the enemy on land.

The JHSV was used in a tactical environment for the first time during Bold Alligator 2014, held in early November. During the exercise, about 11,000 Marines and U.S. and international sailors floated off the North Carolina and Virginia coasts, conducting amphibious assaults and operations ashore.

O'Donnell said the JHSV performed well, although it was operated by a civilian crew and there is still much to be tested to determine how well it will work in real-world combat operations and how it can be incorporated into real-world missions.

He added that there has been a tendency to focus on surface connectors. While he said that air assets like the MV-22B Osprey can't carry the amount of troops and equipment ashore needed for a large-scale amphibious invasion, he said they can carry a small initial invasion force of Marines ashore to mitigate threats and set the conditions for a larger follow-on force and resupply.

Exactly what the years ahead will hold for the Corps' amphibious missions remains to be seen. But O'Donnell expressed encouragement, saying sea basing, which prepositions Marines and equipment close to potential hot spots, and other developments in doctrine and gear are heading in the right direction.

"What was a PowerPoint a few years ago, we are now doing," he said.

As O'Donnell addressed the symposium Wednesday, Marine and Navy leaders including Commandant Gen. Joseph Dunford were meeting at the Navy Yard to further develop details for joint operations in an amphibious anti-access area denial environment, he said.