Within days last year, one recruit at Parris Island was critically injured and another died.

The back-to-back tragedies came amid ongoing hazing investigations at the Marine Corps' East Coast training depot, but investigators found no evidence that either recruit had been maltreated or abused.

Kristian Gashaj, 19, remains in coma after jumping from the second story of a building at Parris Island on Oct. 28, according to a redacted copy of an investigation obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

Zachary Boland, 18, died of pneumonia on Nov. 4, according to the investigation into his death, also obtained by a FOIA request. Despite being sick for several days, Boland did not ask for help likely because he was afraid of being dropped from recruit training.

No changes have been made to recruit training in the wake of the two incidents, said Parris Island spokesman Capt. Adam Flores.

"Recruits are always encouraged to seek medical care at any time, regardless of the associated training being conducted," Flores told Marine Corps Times. "The command also emphasizes the importance of looking out for signs and symptoms of illness to both the drill instructors and the recruits."

Gashaj had arrived at Parris Island on Oct. 24, and when the incident happened was still in processing for recruit training before being assigned a unit.

On Oct. 28, Gashaj was being escorted to a classroom to join the rest of his platoon when he "stopped abruptly, squared himself to the open balcony, grabbed the hand rail on top of the balcony's balustrade with both hands … and propelled himself over the railing in one fluid motion," the investigation says.

Recruits told investigators that they never saw drill instructors or other recruits mistreat Gashaj; in fact, several recruits had tried to help Gashaj accomplish his tasks, according to the investigation.

Gashaj had displayed odd behaviors after arriving at Parris Island, including mumbling to himself, saying things aloud as if he were having a conversation with someone who wasn't there, crying, and sitting up in his bed at night staring into the distance.

He often moved slowly in response to commands and failed to understand basic instructions, according to the investigation. Still, none of the other recruits considered Gashaj a danger to himself.

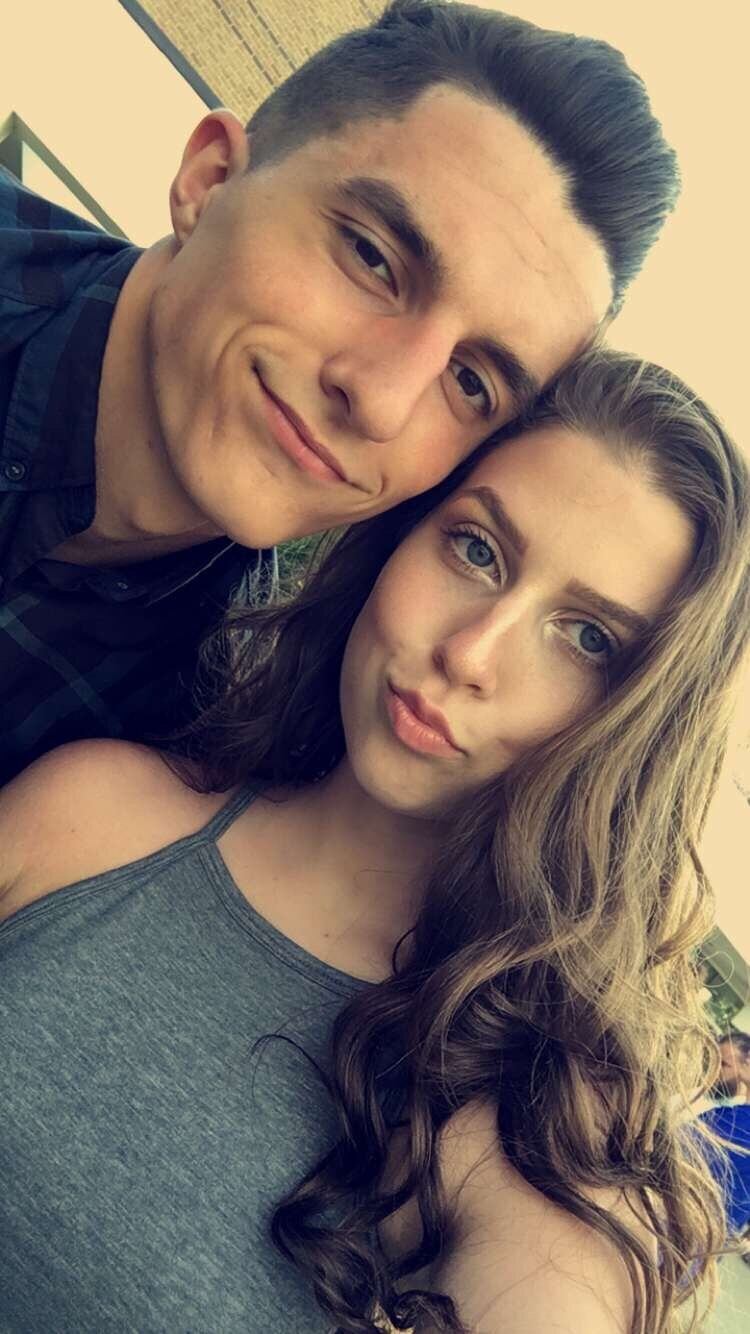

Kristian Gashaj and his sister Kathy at his high school graduation.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Kloe Gashaj.

One recruit told investigators that Gashaj' personality had changed since they were poolees in August. Before Gashaj shipped to boot camp, a Military Entrance Processing Station in Detroit noted that he had been hit in the head by a baseball the month before, the investigation found. The attending doctor did not document any complications, and Gashaj was given six staples in his scalp.

"Based on the provided information, the MEPS [Chief Medical Officer] determined the applicant's medical profile had not changed (fully qualified) and did not place any delay on shipping the recruit," the investigation found.

Gashaj currently is hospitalized in a long-term care facility in Michigan. His family doubts the investigation's finding that he jumped, saying in a statement to Marine Corps Times that they "don't believe that the investigation report is the truth."

One week after Gashaj was injured, Boland was found unresponsive in his bed. He was taken to a local hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

One drill instructor described Boland's death as a "freak accident," according to the investigation.

Boland had arrived at Parris Island on Sept. 24, but he was transferred to the Support Battalion's Evaluation Holding Platoon to be treated for cellulitis, said Flores, the Parris Island spokesman. He was cleared to return to recruit training on Oct. 22.

A medical official determined that Boland likely showed signs of pneumonia in the days before he died, but he could have hidden those symptoms from his drill instructors, the investigation found.

Still, his physical condition noticeably deteriorated before his death. On the seventh day of training, Boland failed a two-mile run, the investigation says. Boland did not need medical help. When a drill instructor later considered putting Boland on trial training, Boland said he "did not want to get dropped and he would work hard to meet the standard."

Investigators learned after Boland died that he had thrown up during chow, but he had asked his fellow recruits not to let his drill instructors know because he wanted to stay in recruit training.

Although recruits in his platoon did come forward when they had medical problems, "Recruit Boland was just not one of those recruits," the investigation found.

Zachary Boland at his high school graduation.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Boland family.

Boland had been laser-focused on becoming a Marine since childhood, and after being hospitalized for cellulitis in September, he likely didn't report being sick because he feared being dropped from recruit training altogether, his parents told Marine Corps Times.

At Parris Island, he likely didn't know how much danger he was in and thought he could power through his illness because that's what Marines do, they said.

"Several of the recruits noticed how sick he was and really did encourage him to seek treatment, but he refused to bring attention to himself because he probably did perceive that to some extent as a sign of weakness," said his father, Bob. "He didn't want to be seen like that all. He wanted to be as tough as any other Marines."

He was never one to complain about being sick or in pain growing up, said his mother, Sam. As a high school senior, he had a severe allergic reaction to poison ivy, but didn't tell his mother about it for three weeks, she said.

Sam Boland hopes that her son's death shows other Marine recruits that they don't have to suffer in silence when they are sick or get injured during training. Getting hurt or sick does not make you weak, and seeking help does not make you less than the healthy recruits who complete training, she said.

"There are a lot of kids that are sick at Parris Island and San Diego," she said. "A lot of people get hurt. A lot of people have broken ribs and they just push through. Then we hear stories about: 'I got hurt during basic training and I'm still struggling with that injury all these years later; I got pneumonia at Parris Island and I almost died; I got this at San Diego and didn't tell anybody that I got a broken rib.' With all of the stories we've heard, it's amazing that more kids haven't died."